Four.

That’s how many times this year the Detroit Tigers have had a man on third, less than two outs, and had him thrown out at home on The Contact Play. I’m not alone in thinking it was more than this, right? Every time the infield makes a perfectly routine play and throws the runner out at home feels like at least the 10th or 20th of the season. Somehow, it’s only been four times that our runner didn’t score and we unified to take up arms against the coaching staff.

There’s just something that feels worse about a runner getting thrown out at home than at the other bases. And surely, going home was the wrong decision, since he was out!

Maybe, or maybe not. Maybe AJ Hinch knows what he’s doing, Joey Cora has his runners well prepared, and the Tigers are playing an intelligently aggressive brand of baseball that just doesn’t always pan out. Since it’s only four clips, let’s watch them all and try to understand better what’s going on. Here they are in chronological order with some relevant context. Maybe a trend emerges, good or bad.

March 27: Torkelson out at home against the Dodgers, man on 1st and 3rd, no outs.

April 19th: Dingler out at home against the Royals, men on 1st and 3rd, no outs.

April 21st: Keith out at home against the Padres, men on 1st and 3rd, one out. There’s strangely no video here, but it’s a ground ball right to the third baseman, and Keith is a dead duck.

June 11th: Perez out at home against the Orioles, men on 2nd and 3rd, one out.

That’s it. Those are the four fielders-choice outs at home that stopped a run from scoring for our Tigers.

In all cases, The Contact Play pushes the envelope and forces the defense to make a quick play. The defense usually sees the runner dancing off 3rd and plays in a bit, adding the risk of a smashed grounder sneaking through that would’ve normally been playable. In a one-run game, opposing managers will even play the infield in specifically to give them a better chance of throwing the runner out at home, even if it opens up more holes for a ball to get through.

Plus, infielders fielding a ground ball and then throwing home isn’t the most common play. Catchers taking a throw from the infield and having to tag a runner is also not that common a play, so there’s a slightly higher chance of an error. It’s small odds, but good teams win at the smallest margins. Putting the defense in an uncomfortable spot is better than not. There’s probably a little more to it, though.

Did you notice how they’re only thrown out at home with other runners on base, suggesting that’s when they’re the most aggressive? They don’t put the contact play on for a leadoff triple, for example. But why?

For three of these plays, it’s simple: an out at home prevents a double play, and allows your other runners to advance into better scoring position. Sure the runner going home is out, but you avoid the double play, and you get a runner from first to second, or from second to third, where you’re again in good position to score on any hit. In the first three examples, a double play could’ve potentially been possible, but the defense went home to stop the run from scoring and extended the inning rather than sacrificing a run to end it.

It doesn’t matter as much when the ball is hit to the pitcher or catcher, but when you’re sprinting On Contact, all you can do is judge if it’s a grounder. It’s logical, it’s boring, and both teams are happy with their decision. The defense keeps a run off the board short-term, the Tigers get another crack at scoring off a pitcher who has already put multiple runners on base that inning, all while continuing their series long war of pitcher attrition by forcing said pitcher to face at least one more batter after already dealing with the stress of pitching with runners in scoring position.

The fourth example is the more interesting scenario. Against Baltimore, Perez broke for home on a very routine play to third and was easily out. There was no trail runner on first, either, so they couldn’t even avoid the double play. What’s the benefit?

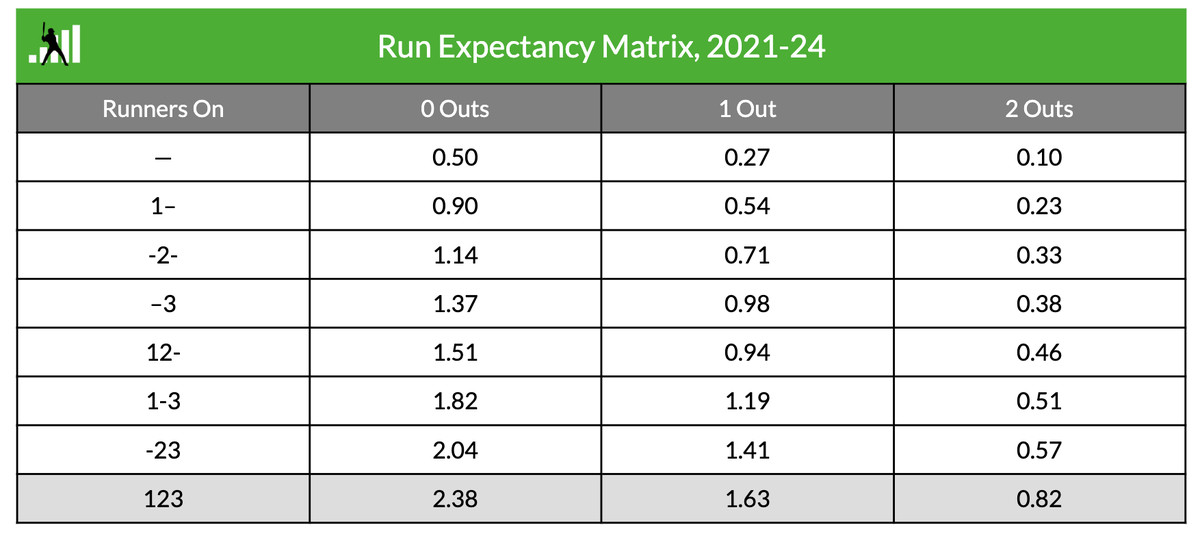

Run expectancy. For those that don’t know, run expectancy is a mathematical average of how many runs score during an inning once a certain base-out situation has been obtained. For example, with a runner on 3rd and no outs, a team scores on average 1.37 runs for the remainder of the inning, but with a runner on 3rd and two outs, they score only .38 runs on average.

Here’s a table I’m taking from FanGraphs showing the run expectancy for every base-out situation from 2021-2024, including those two data points from above. Note that I’m using averages from a multiyear span because there’s a little less noise than there is from the 2025 data, which is similar but a little weird in places.

When making any decision in baseball, one way to evaluate things is by taking the run expectancy of your current situation, assigning a probability to any potential outcomes, then checking what the run expectancy of the future situations are. Once you know the overall odds, you can season to taste depending on the game situation and the players involved.

Today, we’ll be seeing how that applies to sending runners home on bang-bang plays. There are three situations to consider in case there’s a ground ball in the infield: in the first you don’t run on contact, in the second you put the contact play on and the runner scores, or you put the contact play on and the runner is out at home.

In that Orioles game, the initial situation was 2nd and 3rd with one out. If the Tigers do nothing and Perez stays at 3rd, the main outcome is Dingler gets thrown out at 1st, leading to 2nd and 3rd, two outs. This has a run expectancy of 0.57. If Perez goes and is safe, that’s +1 run. Then a runner on 1st and 3rd with one out has an additional 1.19 run expectancy, so that’s a total of 2.19 for those two at-bats in the inning. And if he’s out, which is what happened, that means 1st and 3rd with two outs, for a run expectancy of .51.

Obviously, the scenario where Perez is safe is the best. But when comparing what did happen and what would’ve happened if he were safe to the outcome if they don’t go on contact, you’ll see the Tigers cost themselves approximately 0.06 runs for the chance of gaining 1.62 runs. With some quick back-of-the-envelope math, we can find out he only needed to have a 3.7% chance of being safe to “breakeven” and make the decision a good one.

We can all imagine four ways out of 100 where the fielder takes his eye off the ball, or double-clutches the throw, or the catcher gets short-hopped, or drops the ball in the process of sweeping for a tag. Then Perez sneaks in under a cloud of dust, right? Yes, Perez was out by a mile in that instance, but the condensed nature of the play meant he was either out by a mile or safe on an error. It wasn’t a question of beating the tag on a bang-bang play, it was a matter of forcing the defense not to mess up.

If they choose to keep Perez at third and not run on contact? Well, unless Dingler gets a hit or a walk or hits a sacrifice fly, in which case all this is moot anyway, Perez is still at third, but now you have two outs. There’s no more sacrifice fly possible, and odds of scoring go from 1.41 runs down to 0.57 runs. If you send him and he’s thrown out at home? Well the runner on second advances to third, Dingler is safe at first, there are two outs, but you still have a runner in scoring position on any hit or error. So there’s really no reason not to take the chance, force the defense to make a less common play under pressure, and see if you can press the issue.

Late in the game, decisions get magnified and consequences seem worse than they are, but this was the right call. Making the right decision isn’t always about things working out, but rather about putting yourself in the best position to succeed. Playing for the low odds of an error if the ball is hit directly to an infielder had a better chance of winning the game than doing nothing, as bad as having the tying run thrown out at home seems.

AJ Hinch and the Tigers have crunched the numbers, and they know the odds in each game state. This is just another way in which the Tigers are taking every edge possible and squeezing every ounce of value out of their players. Less tangible is the stress on opposing infields when their manager comes out in a scenario like this and tells them the Tigers are almost certain to break from home on contact, and that they need to be ready. In many of these situations, there’s nothing for the Tigers to lose by sending the runner, and plenty to gain.