Inside most dugouts these days, a baseball game doubles as a film festival. Follow a frustrated hitter back to the bench and chances are he’ll call up the video on an iPad to deconstruct the wayward at-bat.

During a World Series game last fall, New York Yankees slugger Aaron Judge, wielding a tablet, approached Austin Wells and coached him through how to attack a high fastball. In Wells’ next at-bat, he walloped a high fastball 384 feet into the right-field seats.

Matt Dahlgren watches scenes like this play out on TV and thinks of his grandfather.

“I smile internally knowing that the concept of studying their mechanics on film, studying their swings, that started with Babe,” he said.

Babe Dahlgren is best remembered, if he is remembered at all, as the man who replaced Lou Gehrig as the Yankees’ first baseman. You might see him in the background of images on Friday, the anniversary of Gehrig’s searing “luckiest man” speech on July 4, 1939.

Dahlgren is the Yankees player positioned closest to Gehrig on the third-base side during the ceremony. Manager Joe McCarthy stationed Dahlgren, a deft fielder, nearest to Gehrig in case the ailing Iron Horse collapsed. “If he starts to go down,’’ McCarthy instructed, “catch him.”

“Babe always told me that the entire time Gehrig was giving that speech, Lou’s legs were trembling,’’ Matt Dahlgren, 54, said. “Babe would get emotional till the day he died talking about that speech. His eyes would well up and his lips would quiver.”

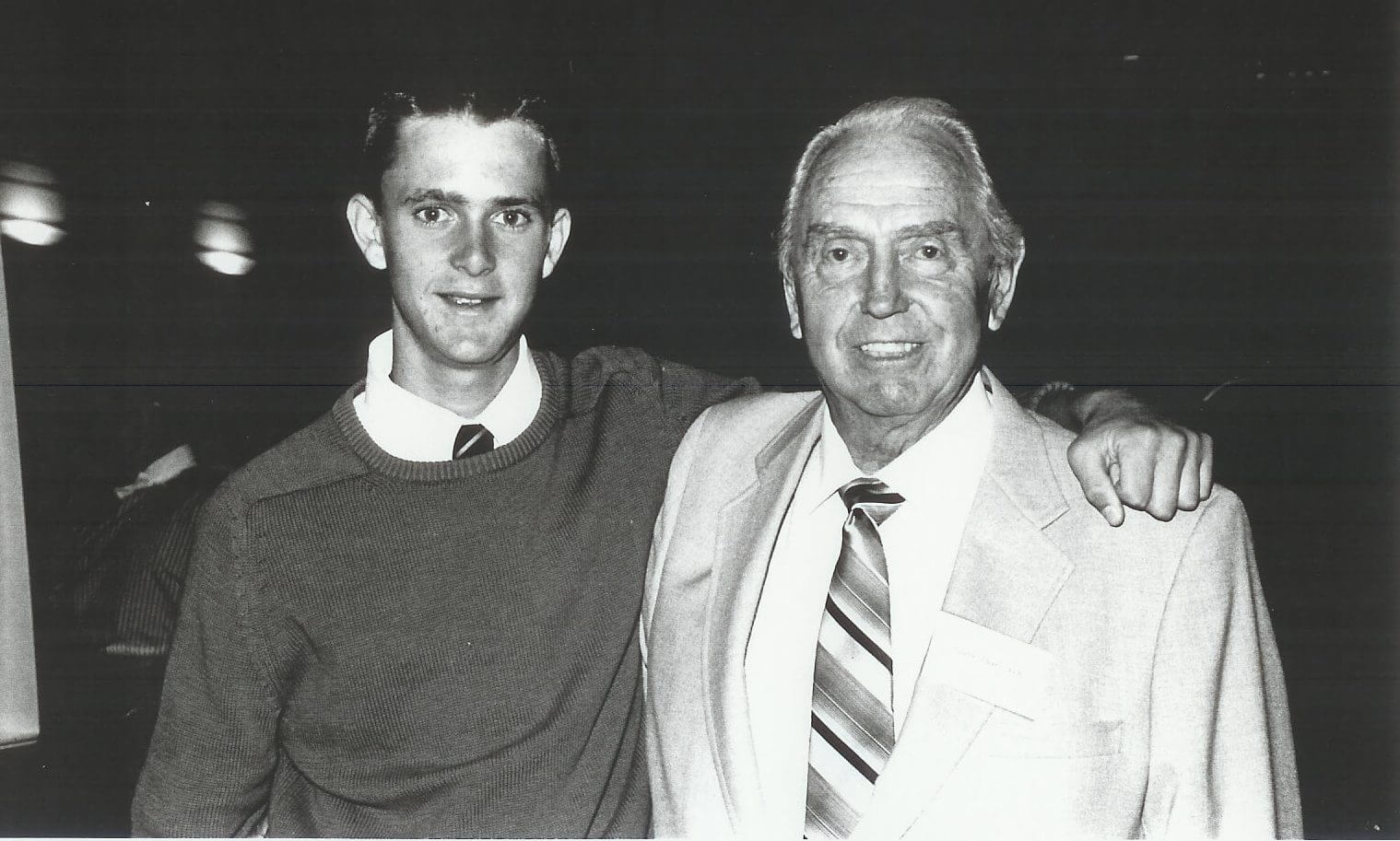

Matt Dahlgren, age 15, with his grandfather during a visit to San Francisco in 1986. (Courtesy: Dahlgren family)

But Ellsworth “Babe” Dahlgren’s lasting contribution to baseball goes beyond joining Wally Pipp as the bookends to Gehrig’s legendary streak of 2,130 consecutive games played.

It involved lugging a Bell & Howell motion picture camera around the ballyard as early as the 1940s, having deduced that recording hitters in action might be useful as a teaching tool. It took decades, and a fateful elevator ride, but Dahlgren became the first major-league coach to implement film study in his instruction, initially with the Kansas City Athletics in 1964.

“I always tell people he’s the first guy that I ever knew that started taking pictures of players,’’ said Jim Gentile, 91, a six-time All-Star who played for that ’64 team, in a recent phone interview.

Dahlgren took a job with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1965, reprising his role as a coach who used film. He made one last go with the Oakland A’s in 1970, when Dahlgren and his camera were summoned midseason to help stir Reggie Jackson out of a slump.

Dahlgren bought his first 8-millimeter camera in 1938 to film attractions on Yankee road trips. This apprenticeship would serve him years later when he invested in top-of-the-line equipment and began recording miles of 16mm footage of hitters’ swings, as well as filming interviews with 25 legends, including Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, Al Kaline and Rocky Colavito.

Such practice is ubiquitous these days. So why isn’t Dahlgren recognized as a landmark figure in the history of baseball cinema?

Why aren’t his invaluable films playing on a continuous loop in Cooperstown?

The trouble began with a missed phone call in the middle of the night, and the capricious nature of the Santa Ana winds.

Sir Isaac Newton had his apple. Babe Dahlgren had Joe DiMaggio.

Dahlgren’s origin story as a cameraman can be traced to watching Joltin’ Joe from the dugout while they were Yankees teammates in the late 1930s and early ’40s. Dahlgren, also a right-handed hitter, wanted to know what made DiMaggio’s swing so much better.

So, for DiMaggio’s at-bats, Babe would take to covering his face with his cap and isolating his view of the hitter by watching through an eyelet – one of the little holes that allows a cap to ventilate. That let Dahlgren block out all distractions and focus on the hitter’s mechanics.

“That was the original iPad,’’ Matt Dahlgren said. “That’s how he studied it. It’s amazing how far it’s come.”

My great-grandpa replaced Lou Gehrig on this day in 1939. Big shoes to fill. I wish I could have met him. #BabeDahlgren ❤️ pic.twitter.com/Dz827RMMBW

— Emma Dahlgren (@emmadahlgren2) May 2, 2025

On May 2, 1939, in his first game as the successor, Dahlgren went 2-for-5 with a home run. He later told The Sporting News: “(Gehrig) grabbed me when I got back to the bench and shouted at me, ‘Hey, why didn’t you tell me you felt that way about it? I woulda got out of there long ago.’”

But over his 12 big-league seasons, Dahlgren batted .261 with 82 homers and a .713 OPS. Teams did not have batting coaches when he started playing, but he spent his career looking for someone who could break things down.

The closest he came to a hitting guru was in 1941, not long after joining the Chicago Cubs. Manager Jimmie Wilson sauntered up to Dahlgren in the clubhouse one day and said, “Babe, let’s talk hitting.”

Wilson threw a glove down on the floor of the clubhouse to serve as a makeshift home plate. From there, Wilson demonstrated different stances and had Babe stand next to the glove and do the same.

Dahlgren went on to hit 23 home runs that season, the only time in his career he topped 20. Bolstered by his thoughtful new approach, he began keeping detailed notes on 3×5 cards about certain pitchers and stored them away in little metal boxes.

But he soon concluded that pictures were worth a thousand words.

After two final seasons in the Pacific Coast League, Dahlgren retired from baseball in 1948 and embarked on a second career as an insurance salesman in Arcadia (Los Angeles County), Calif.

But the game lured Dahlgren back, and it should surprise no one that the man who studied DiMaggio through the eyelet of his cap became a scout. Hired by the Kansas City Athletics, he had a knack for the job.

Dahlgren identified a star in the making after watching a youngster named Roger Maris take batting practice for the Cleveland Indians during spring training in 1957. Maris had yet to play a major-league game, but Dahlgren saw a swing that reminded him of Gehrig’s.

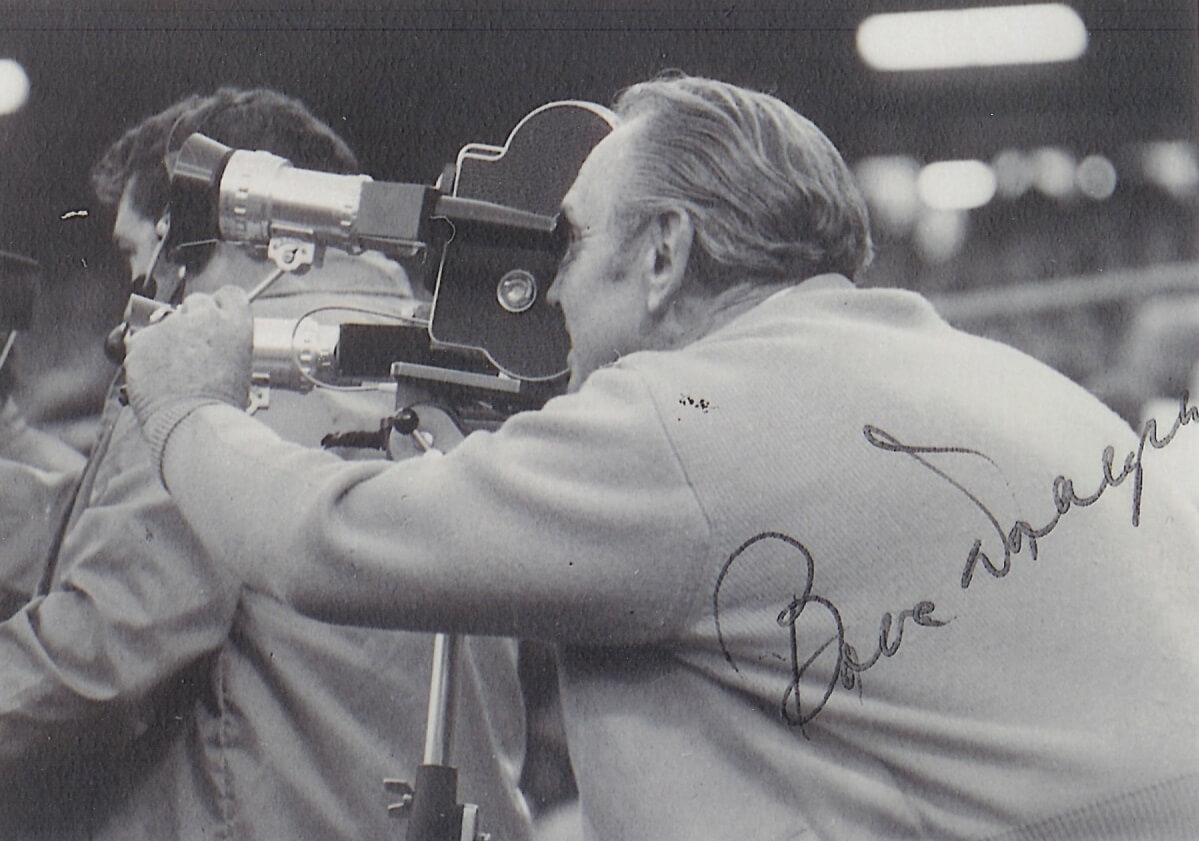

Babe Dahlgren filming the action at the Oakland Coliseum in 1970. (Courtesy: Matt Dahlgren)

Two years later, when the Athletics traded Maris to New York, Dahlgren penned a letter to Yankees general manager George Weiss. The Los Angeles Times unearthed that letter for a story published in September 1961, when Maris was on the verge of setting the single-season major-league record with 61 home runs. It read:

I think you won several pennants in obtaining Roger Maris. I honestly feel that as time passes, this deal will be considered a masterstroke. That boy is capable of slamming between 60-70 homers a year, and he has the short porch to hit with the ability to pull.

During this time, Dahlgren was coaching his teenage boys, Ray and Don, and noticed how quickly he sussed out what was working with their swings and what wasn’t. He was a mechanic who could spot the problem as soon as he opened the hood.

Dahlgren wrote in his unpublished memoirs about the thunderclap feeling of deciding, in 1958, that he wanted to become a hitting coach.

“When you feel in your mind that you can identify the ingredients that must gel in their proper order during the swing progression … you want to shout to the world that you know how it’s done, and how to help others.

“To accomplish this feat, I decided to film the action and to learn how to use cameras and sound and how to splice the film and put the story together step by step.”

He dedicated the next years to filming the swings of the game’s greats, and leaning on his connections to secure one-on-one interviews about their craft. (On the day a retired DiMaggio demonstrated his approach at Yankee spring training camp in 1961, his ex-wife Marilyn Monroe waited patiently on a dugout bench.)

Matt Dahlgren remembers visiting his grandparents’ house in Bradbury Estates, a gated community in Los Angeles County, in the 1970s and stepping into Babe’s “dark little office” just off the family room.

“I just remember seeing shelves lined with silver film canisters,’’ Matt said. “He was like a mad scientist. It was priceless, priceless film.”

Five years after embarking on his quest to film hitters, in December 1963, Dahlgren pulled his car into the Statler Hotel parking lot on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles.

This was the site of the Winter Meetings. With a canister containing his life’s work, a two-hour film on hitting called “Half a Second,” Dahlgren wandered the halls, like so many others in Hollywood, looking for his big break.

“The lobby was just buzzing with baseball people – GMs, farm directors, owners,’’ Matt Dahlgren said. “He felt that if somebody would be willing to at least listen to him right out of the gate, it would be Charlie Finley. He felt that Finley was just kind of a free-spirited guy.”

Dahlgren finally spotted the Athletics executive waiting for an elevator and made a mad dash before the doors opened. Finley apologized; he had plane reservations and was running late. But Dahlgren knew from his days as an insurance salesman how to keep the conversation going, and he stepped inside the elevator.

“Charlie, you are dealing with baseball players every day, and you can’t afford to trade away talent. You’ve got to know what to look for in a batter, and that is what my film is all about!” Dahlgren recalled saying, in his memoirs. “I could see I struck a nerve, so I shut up, giving him time to think. The elevator stopped at his floor, and we got out.

“He stopped in the hall and asked, ‘Where is the film and how long would it take to get it?’’’

They set up a projector and watched the film in Finley’s suite, where the Athletics owner grew so enamored he canceled his flight.

The Athletics already had Luke Appling as a batting coach, but Dahlgren came aboard as a second voice, in charge of filming both hitters and pitchers.

By spring training in Bradenton, Fla., the media was abuzz about Dahlgren’s new approach. Joe McGuff of The Sporting News wrote that this would be the first time baseball would embrace an expanded role for images.

Blue Jays first baseman Vladimir Guerrero Jr. studies on an iPad on May 28. In-game film study is a common sight. (Kevin Jairaj / Imagn Images)

Gentile, who was 31 that season and three years removed from leading the American League with 141 RBIs in 1961, was open to anything as Dahlgren made the rounds asking players if they wanted to be filmed for analysis.

“I said, ‘You want to do it on me’” Gentile recalled by phone from his home in Edmond, Okla. “And he did.”

Dahlgren filmed the 6-foot-3, 210-pound slugger taking his left-handed hacks. Then the two headed underneath the stands, where Dahlgren hung up a white bedsheet to serve as the screen, their version of the video room.

“He’d talk about it: ‘Maybe you’re pulling your right shoulder too quickly. That’s why you’re tipping the ball instead of hitting the ball hard,’’’ Gentile said.

Still, the A’s performance in ’64 did nothing to launch baseball’s film revolution. They finished near the bottom in almost every offensive category, and Finley fired most of the coaching staff after a 105-loss season.

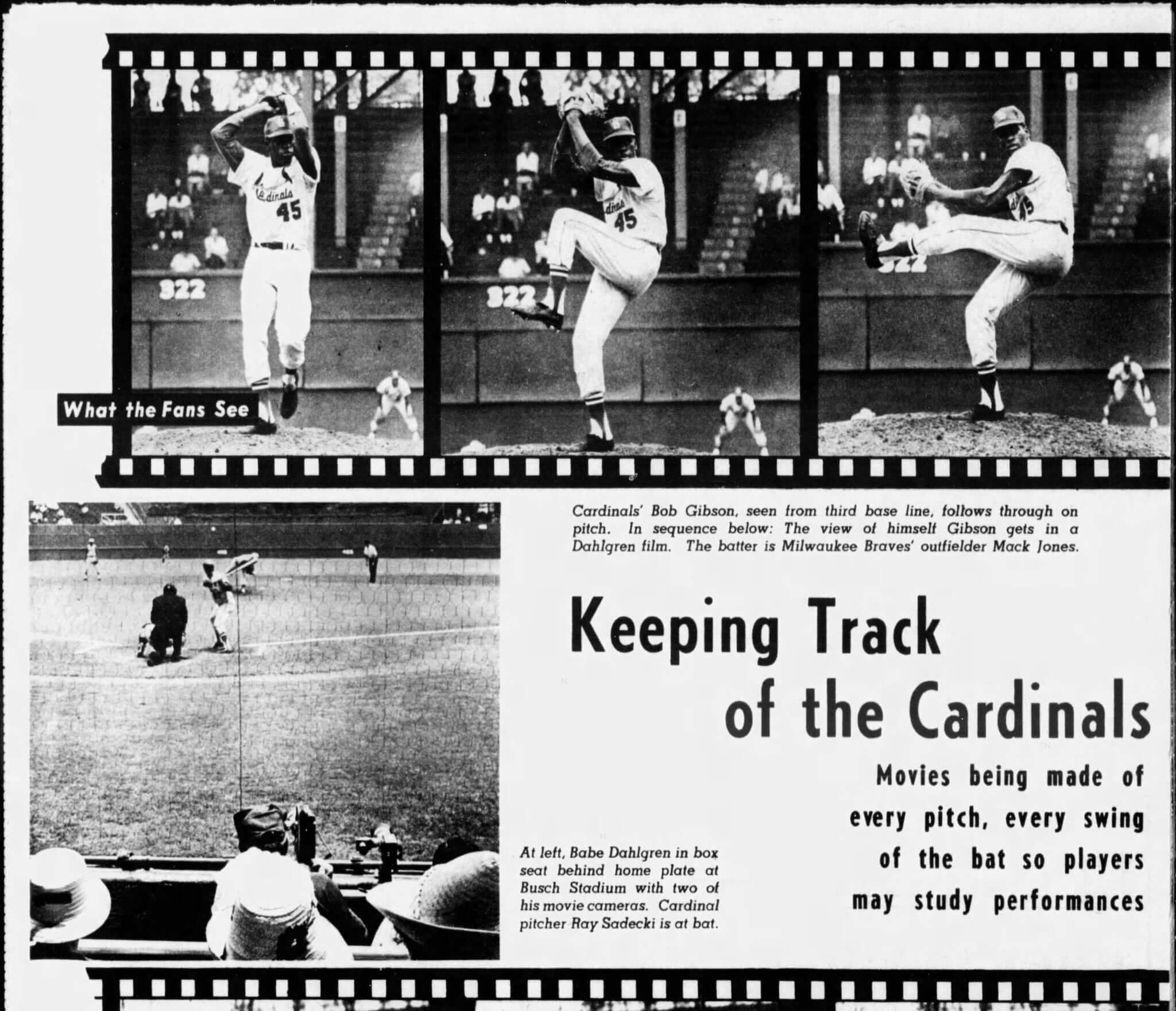

The Cardinals hired Dahlgren for a similar role in 1965. St. Louis manager Red Schoendienst was an early proponent, recommending that players watch the movies that showed them when they were in the groove.

The St. Louis Dispatch at the time underscored the novelty of the approach: “Dahlgren has been shooting hundreds of feet of film during every game… Thus, a player may study his most recent form on a movie screen before taking the field again, just as easily he may compare his current form with earlier performances.”

That Cardinals team, fresh off a World Series victory, went 80-81 and finished 16 1/2 games out, again leaving Dahlgren out of a job.

A newspaper clipping of the St. Louis-Post Dispatch from 1964. (Courtesy: the Dahlgren family)

He had one last gasp, reuniting with Finley and the A’s midway through the 1970 season. Reggie Jackson, coming off a 9.3 bWAR season in ’69 that heralded the arrival of a superstar, slumped out of the gate, batting .228 in the first half with 76 strikeouts in 254 at-bats.

Dahlgren was summoned to join the staff on July 23. “It was kind of a last-ditch effort by Charlie to try to get Reggie going,’’ former A’s clubhouse manager Steve Vucinich said in a phone interview.

Dahlgren quickly discovered he didn’t have much to do. Jackson was in a bad place mentally, but his mechanics remained impeccable. “In all my years in baseball, I’ve never seen anyone with a better swing,” he told the Cumberland Evening Times, “and that includes Gehrig.”

Still, Dahlgren savored one breakthrough. During a trip to Detroit, Reggie called Dahlgren’s room. “Babe, do you have time to show me some film?” So they sat together in a darkened hotel suite as images flickered on a white sheet.

“Geez, I look like horse(bleep),’’ Jackson said, according to Dahlgren’s notes.

As it turns out, Jackson had the same problem Dahlgren once had: He was lunging. Dahlgren suggested a way to avoid getting out on the front foot, the kiss of death for a power hitter.

The next day, on Aug. 30, 1970, Jackson walloped his first dinger in a month, a pinch-hit home run that traveled an estimated 440 feet to dead center field against the Tigers.

That was the last hurrah for Dahlgren, who retired and headed back to his home in Southern California. Matt, who lived in nearby Irvine, would grow up to visit Bradbury Estates during summers and climb into a reclining chair while Babe spun yarns about baseball gods.

“We’d stay up late into the night and just talk about baseball,’’ Matt Dahlgren said. “That’s all I wanted to do was hear his stories.”

They were lucky to get out alive.

The phone call came in the wee hours of Nov. 16, 1980, prompting Babe, nearly 70, to hoist himself out of bed, shuffle to the phone and lift the receiver just as it stopped ringing.

As Dahlgren tottered back toward bed, he noticed a red haze radiating through the skylight. “That’s odd,’’ he thought.

Dahlgren returned to his bedroom and tugged on the blinds for a better look. That’s when he saw the inferno. His two-acre property was ablaze, engulfed by a hard-charging Southern California wildfire. Gusts from the Santa Ana winds that night hit 90 mph.

“He screamed at my grandma. ‘Mabel, get up! Get up! We got to get outta here!’” Matt recounted. “So he grabbed the clothes they had had on the night before that he had draped over a chair.”

There wasn’t time to grasp much else. Dahlgren snatched a handful of Mabel’s jewelry off her dresser. He wrapped his hands around his 1938 World Series ring.

But all that film? All those silver canisters?

Matt Dahlgren responded to those questions by texting a picture. Like his grandfather, he knows the power of images.

It’s a grainy photo of Babe Dahlgren standing by a brick fireplace, the only structure of the home still standing. Elsewhere in the image, shellshocked children walk on a floor of ash. One of those children is Matt.

“It was still smoldering,’’ he said softly. “I can still smell it to this day.”

One person died and 62 homes were destroyed in those Bradbury-Duarte fires, which blackened an estimated 6,200 acres.

The lone fatality was Dr. John Hervey, 47, who died of a heart attack while trying to evacuate. Hervey’s wife, Mercedes, is the one who tried calling Babe and Mabel at 3:30 a.m., trying to warn them to get out.

“That woman saved my grandparents’ lives,’’ Matt said.

Dahlgren’s life’s work, however, melted into the ashy rubble. Those silver canisters, the treasure trove of Cooperstown legends showing off their swings, the interviews with DiMaggio and Williams, all lost.

“Everything he had — 18 years of professional memorabilia, all of his film, his book he was writing, the bat he hit a home run in the World Series with — everything gone. Gone,’’ Matt Dahlgren said.

Late in life, Dahlgren developed advanced dementia and ultimately died of natural causes in Arcadia on Sept. 4, 1996. He was 84. His final years remained happy, though, even if his movie’s ending wasn’t.

“He didn’t lose his will to live,’’ Matt said. “He rebuilt. He enjoyed the hell out of his family and watching us grow. And he never complained.”

When baseball remembers Gehrig this week, there ought to also be a tip of the cap to the man who followed him.

Nearly a century ago, Babe Dahlgren looked through the eyelet of his cap to watch DiMaggio’s swing.

What he saw was the future.

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Associated Press photo, additional imagery courtesy of Matt Dahlgren)