If you’re anything like me, you’ve found yourself pleasantly surprised a couple of times this year, when Matt Wallner really caught hold of a ball. The first time I noticed it was June 7, when the Blue Jays were in town. Wallner blasted a ball from Toronto starter Kevin Gausman down the right-field line. He’s hit balls much harder, but though it was launched 41° upward at less than 100 miles per hour off the bat, it carried out of the park for a homer.

It didn’t surprise me that the ball cleared the fence. Off the bat, it was clear that he’d gotten enough of it for that, given the cozy dimensions of the corner and the way he barrels the ball when he gets off an ‘A’ swing. I assumed, though, that the ball would turn foul. It was hit close to the line, but instead of the spin pushing it foul as it traced its steep parabola, it stayed true. In fact, it seemed to drift slightly away from the pole.

MTZxbjNfWGw0TUFRPT1fQUFRQ0J3QURBQUFBQ3dNQkFBQUhCZzllQUFOWEFBTUFWZ2RYVXdwWEFGRlFWQWRV.mp4

In this particular case, there’s some reason to credit Wallner for keeping it straight enough to get a home run instead of a foul out of a mistake pitch by Gausman. His swing is slightly under the ball, to be sure (hence the very high launch angle), but he keeps his hands in and gets to the ball very directly. It’s a 96-mph fastball from Gausman, so far from being early, Wallner is right on time. His steep attack angle gives the ball backspin, but his attack direction at impact is just 6° to the pull side, so he doesn’t impart much sidespin on the ball (the way most swings that result in long, pulled flies do). A compact, on-time swing can help keep that ball fair. The Statcast readout of the swing tells that story. He didn’t catch the ball quite on the sweet spot, but the arc of his swing and the timing made it easy to maintain true ball flight.

Two weeks later, though, Wallner did get a little bit lucky—or did he? More on that later. For now, consider this ball, the first hit Jacob Misiorowski gave up in his big-league career.

b0daZDlfWGw0TUFRPT1fRGdnRlZGd0dVd0FBWGxzTEJ3QUhCUVZWQUZsWFYxVUFVVnhUQTFWV0JBRUJWZ3ND.mp4

This is an 0-1 slider, and Wallner is a hair earlier on it. He would have been way early, but because Misiorowski is who he is, the ball was coming in at 93 miles per hour. Thus, Wallner’s last-minute adjustment didn’t need to be a major deceleration of the bat; he just had to dip slightly to find the lower half of the ball. It’s fascinating, in watching this pitch’s equivalent of the Statcast visualization above, to see the differences in the swing he got off. Again, he catches it just up the bat from the sweet spot, this time with more hook on it. Reading slider late, you can see him flatten his swing and go straight through the lower half of the ball.

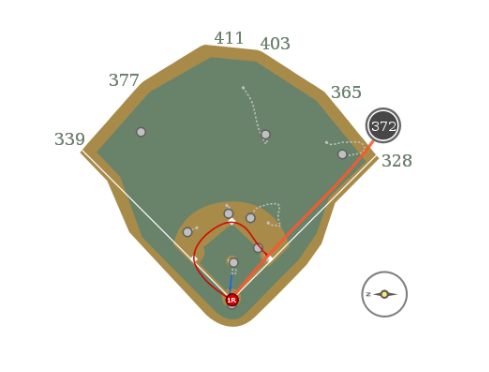

Doing that took some sidespin off the ball, too, relative to what we’d normally expect when a ball sails down the line. Because I couldn’t see him doing that in real time, though, I was even more certain that this ball would twist foul—and when you see the overhead visualization of the trajectory of the ball, you can see how reasonable that belief was, and how strangely the actual flight of it defied that belief.

Almost any ball hit down the lines will spin toward the lines. That’s an axiom of baseball, because of the kinds of swings and contact that generate such batted balls. We’ve now seen two examples of Wallner’s swing helping kill that sidespin, but even accounting for that, the ball should have had enough spin to push closer to (or beyond) the pole.

Fast-forward another three weeks with me, though, because we’re about to find the most extreme example of this phenomenon. In the bottom of the second inning on July 9, Wallner got into a 2-1 slider from Cubs starter Cade Horton.

OHl3ajJfWGw0TUFRPT1fQWxVQ0FGY0NCVk1BWGxZRFVRQUhWRklIQUZrTlV3SUFVUU5VVkFWWENBUlNCUVFI.mp4

The swing tells us the most interesting story yet about this one, because unlike Misiorowski, Horton had Wallner sitting on a fastball, and unlike Misiorowski, Horton has a big speed differential between his heater and his breaking ball. Wallner was ready for 96 mph, but he got 85. As a result, you can see him actually throttle back from his maximum bat speed before contact. When baseball people talk about the value of raw strength in generating power, this is the kind of thing they’re talking about. Not many hitters are strong enough to slow down their own bat after reaching a speed just under 80 mph, while maintaining enough speed to do damage when they catch the ball flush.

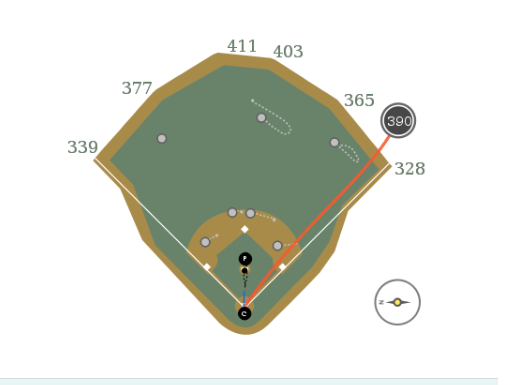

Unlike the homer against Gausman (7.2-foot swing length, 6° attack direction) and the one against Misiorowski (7.4 feet, 16°), though, this is a long swing on which Wallner was way out in front (8.1 feet, 20°). He gets the sweet spot here, which is why the ball leaves his bat at 113 miles per hour, but he’s way around it and working steeply uphill through it. The 43° launch angle sends the ball soaring. It’s right down the line. This ball should go foul. Again, though, it didn’t. Again, it moved away from the line.

We have to acknowledge that Wallner is capable of unique, freaky contact. His blend of bat speed and swing plane can generate fly balls down the line with less sidespin than most of them have. That’s one factor in these (and a few others, which we’ll leave out here in the name of brevity) balls going for extra bases. Fascinatingly, though, another factor might be Target Field’s architecture itself.

Having seen a few of these balls turn improbably toward the plaza, I reached out to Weather Applied Metrics’s Ken Arneson. A long-time baseball writer, Arneson now plays in the sandbox of the endlessly complex, idiosyncratic interactions of weather (especially wind) with sports, and baseball is one major subject of study and analysis for the company.

“Target Field has a gap between its roof and the top of its upper deck,” Arneson wrote. “The top of the upper deck is about 122 feet above the field and the roof is about 150 feet above the field. As the wind tries to squeeze through that 28-foot gap, it will accelerate.”

That’s true; it’s the result of the Venturi Effect, which describes the way pressure is reduced when speed increases as a fluid moves from a larger space to a smaller one.

“So if you have a southwest wind blowing perpendicular to the first base line … and you have a fly ball with an apex around that height (122-150 foot apex), you’re going to get a kind of perfect storm to push the ball back towards the field, and counteract the spin that wants to hook the ball foul,” Arneson continued. “Under those conditions, the wind will push the ball back towards fair territory about 5-6 feet with a 10 mph wind.”

Batted balls even to right-center will be unaffected by this microatmosphere. The Venturi Effect wears off quickly once any wind passes through the aperture between roof and stands, petering out not far beyond the right-field line. If a player is strong enough to consistently hit the ball up into that space far down the line, though, it can make a substantial difference—especially if that player has an unusual swing that results in balls down that line not having as much sidespin as most hitters’ similar shots would.

Arneson notes that the wind pattern needed to create this phenomenon is relatively rare, at least as a prevailing wind on a given day. With the right momentary gust or buffet, though, it doesn’t have to be blowing that way the whole day. Wallner clearly got some help from the elements on these homers, even if it was neither the sole nor the decisive factor in their staying fair.

Baseball is wonderful, because it’s so hard to apply any rule too broadly. It’s not just the deep right-field corner at Target Field; each batter and pitcher is a microenvironment of their own. Wallner’s special skill set begets a special set of batted balls, which can benefit from a special effect of the home park in which many of them are hit. It’s a bit of serendipity—a tiny hometown advantage for a Minnesota native who plays for the home team. Next time he hits a long drive down the line, allow yourself to hold onto more hope for the ball to stay fair than you normally would—and if it does, say a little baseball prayer of thanks to the Wallner winds of Target Field.