In the past three years, baseball fans have watched with interest as a new, remarkably feckless team makes a push for the worst record of all time, and this year’s Rockies seem like a good contender. They have the worst ERA in all of baseball, and their starting pitching has been historically troubled. If the season ended today, their 6.17 starting rotation ERA would be the seventh-worst in MLB history.

In the age of pitch limits, this has put immense pressure on their bullpen as the starters often hand them impossible situations early in the game. Much has been written about the elements at Coors Field that bedevil Rockies pitchers, and much will be written about one of the most doomed run prevention efforts in MLB history (the 2025 Rockies), but I’m only interested in one young, talented reliever trying to break through under perhaps the worst circumstances imaginable.

Juan Mejia is a rookie reliever with a hard fastball and good slider who celebrated his 25th birthday 25 days ago. The mostly unknown righty was demoted once and then recalled in May when the team needed fresh arms. Looking at Mejia’s game logs from the beginning of the season is a good way to understand how bad the Rockies have been this year and how low Mejia was in the bullpen hierarchy.

In all of his first 12 appearances, the Rockies were losing when he entered, and in seven out of those 12 appearances, they were losing by five runs or more. In two of those games, he entered with his team losing by 12 runs. Seven of the eight earned runs Mejia had surrendered in that span came in two blowouts that he entered in the fourth inning.

The first came against the Padres when he had gotten seven outs just two days before, and the other came against the Mets in his first time pitching back-to-back days in the MLB. Mejia had to contend with a very unpredictable and imbalanced workload at the beginning of the year, and I would guess he did not envision pitching in the fourth inning on either of those days.

However, Mejia has flashed enough potential to earn himself more trust and has even recorded four holds in the second part of the season. At this point, Mejia’s ERA is 3.97 with a 3.70 FIP and .726 OPS against. His K% and BB% are both better than average, and his 30.3% CSW is a sign of his stuff’s potential.

Mejia currently has only two pitches. He has a 96.2 mph rising four-seam fastball with 11.8 inches of iVB and 1.7 inches of iHB and a sharp and diagonally breaking slider with -14.5 inches of iHB and -3.1 iVB. His slider doesn’t get a lot of whiffs, but it is very effective in the zone as it has a 17.8% called strike rate (MLB average on sliders is 14.5%).

As a result of the altitude, pitches break significantly less at Coors Field than they do away from it, which changes the nature of Mejia’s arsenal. Though the very small sample size means they should be taken with a grain of salt, Mejia’s home/road splits so far are stark.

Part of this is, of course, the randomness of small sample sizes and the fact that balls travel much farther in Denver. But his individual pitches change, too.

Let’s look at those.

As you can see above, both his fastball and slider have significantly more break on the road, even with effectively the same spin rate. Now, for how well they perform:

As you can see in the tables above, Mejia loses over four inches of break on his fastball and almost three inches on his slider when he pitches at home instead of on the road. This, counterintuitively, has coincided with more swings and misses. But, unfortunately for Mejia, this is more than counteracted by a decrease in called strike rate as his pitches lose movement and he struggles to control them. One explanation for the whiff increase despite much worse overall performance is that he throws fewer pitches in the zone at home, leading to fewer called strikes but more swings and misses when hitters do swing.

As a result of the decreased movement, Mejia has gotten hit a lot harder at home, even as whiffs have increased. I was hoping this whiff/called strike change might represent some strategy on Mejia’s part that he can control—perhaps, for example, the different movement profile at home makes the slider a better chase pitch, so he throws it out of the zone more.

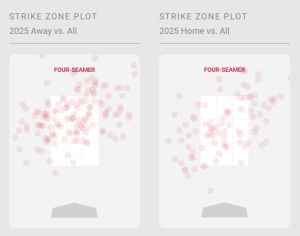

However, when I looked at where his pitches are actually going, it seems like he just can’t command his pitches at home. His fastball has the most dramatic change, losing 4.1 inches of rise on average at home, and you can see from a pitch plot comparison how pitching at home gives Mejia difficulty.

On the left is his fastball pitch plot on the road. Though the number of pitches makes it hard to see, there is a concentration of pitches up in the zone—where you would want to throw a fastball with that shape. However, his plot at Coors, which is on the right, shows a wild scatter of pitches with a concentration of pitches middle-middle and middle-away—not typically the place you want to keep throwing your fastball.

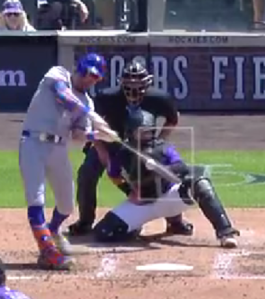

I’m not in Mejia’s or his catcher’s mind and can’t know for sure, but Mejia may be trying to hit the upper third of the zone, but, because the pitch doesn’t rise as much as it usually does, it’s flat and lands right in the middle of the zone where hitters like it. This is what happened the second time he gave up a home run to Jeff McNeil. The catcher wants the pitch up and in (watch him flash the glove to the top-left corner as Mejia starts his motion), but Mejia misses a couple of inches low, making it belt-high and inside, where McNeil hits home runs.

The confusion of seeing a pitch remain in the hitting zone when it should break might make Mejia more cautious to attack hitters and lead to fewer strikes. Also, overcorrecting for the change in movement might explain the more scattered pitch plots at home.

That it’s difficult for pitchers to adjust to Coors Field is not a secret. And it is easy to throw your hands up and dismiss Mejia’s struggles at home as simply physics and impossible to fix. But the Rockies are also failing to mitigate the damage—something they should do automatically at this point. His fastball, though better on the road, is still decent at home, but his slider goes from a .203 wOBA against on the road to a .535 wOBA when he pitches at home. This isn’t necessarily just a result of the slider being worse, but the different fastball movement could be hurting the slider’s performance, too.

Adding a cutter would improve his tunnels and make both of his pitches perform better, as well as giving him an offering less affected by the high altitude, which he might be able to locate more consistently at home. Additionally, he has dramatic splits because his slider is much less effective against lefties, and he could use a changeup or a decent off-speed pitch against lefties.

This is all easier than it sounds. Adding MLB-level offerings is a difficult task, but that’s why pitching development teams are there. This analysis is centered around the unalterable challenges of the mile-high air, but a pitcher as talented as Mejia can adapt to the elements and become effective. The Rockies have commendably given Mejia more consistent usage in more important situations as he has proven himself. But Mejia has a lot of upside left to unlock, and to do so, he will have to overcome the albatross of thin air that has menaced Rockies pitchers since the franchise’s creation in 1993.