In 2024 Rays catchers managed only 1.2 fWAR, with most of it on the defensive side of the ball. So they went out and signed Danny Jansen, a highly-regarded veteran free agent, to fill that hole at and behind the plate.

So far Jansen been among the worst pitch framers in baseball. And that’s weird! To understand just how weird, we need to back up.

In 2011, Mike Fast published his research into the impact of catcher framing, expanding on previous work done by Dan Durkenkopf and by Bill Letson. The following season the Rays signed 37 year old journeyman Jose Molina, the star or Fast’s findings, to be their starting catcher.

All of these early attempts to quantify framing — how the way catchers receive pitches influences the calls made by umpires — arrived at a similar and startling conclusion: catchers have a lot of power over whether a pitch near the edge of the strike zone was called a ball or a strike. The revolutionary finding wasn’t that the framing skill existed. We already knew that. It was the magnitude.

Before being quantified, framing had been treated as an afterthought. But it turned out to be the most important aspect of catcher defense by far, and arguably the most important part of a catchers’ entire job. The differences in run value between the best and worst framers were every bit as large as those between the best and worst hitters.

Fast forward 14 years and the catching landscape is different. There will never be another Jose Molina because there are no more Ryan Doumits — these days all catchers can catch. The average skill is higher and the spread in framing talent is more narrow. Catchers work more on their defense now than they ever have before, just to be acceptable.

Even the technique has changed.

One Knee Down

It used to be that most catchers crouched. Now almost everyone puts a knee down on almost every pitch.

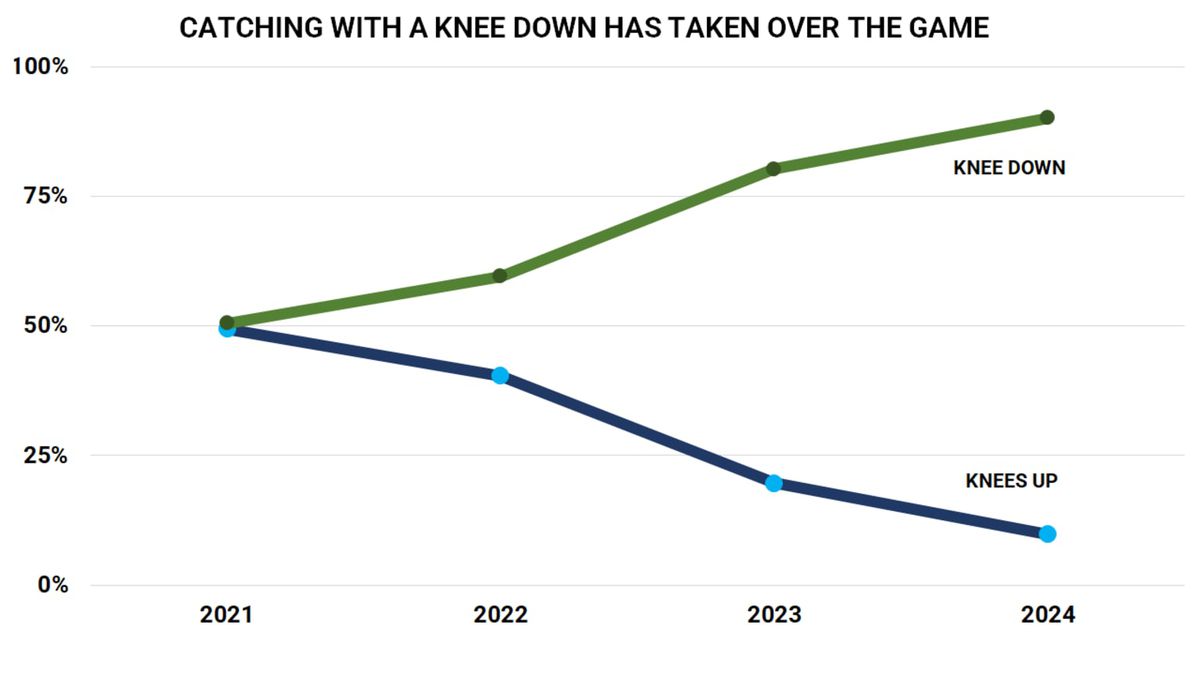

Travis Sawchik wrote an excellent article about how the Twins adopted one-knee-down catching as an organizational philosophy beginning in 2018, and Baseball America has tracked the proliferation through the league. Just last year before the World Series, Mike Petriello wrote about the phenomen, sharing this graphic:

Mike Petriello

The basic story is that catching with one knee down helps with framing, especially for tall catchers (but not just for them), and especially on pitches near the bottom of the strike zone. Lowering the base allows catchers to receive the ball without their glove needing to move down to the catch point.

And while intuitively it seems like putting a knee down would hurt a catcher’s ability to block and throw (which are relatively less important components of catcher defense than is framing), the numbers don’t support that.

Putting a knee down may also decrease the physical wear catchers experience during the season.

And that brings us to Danny Jansen.

The Holdout

Begin with the understanding that Jansen has been a good catcher for a long time, especially at blocking pitches. Since he entered the league in 2018, according to the Statcast blocking metric, Jansen has blocked 62 more pitches than an average catcher would have, best in the league (second best on a per-game basis) and good for 16 runs. He did this mostly with both knees up. He was quick and comfortable in a crouch.

And despite having his knees up he was a decent framer as well.

There are two main publicly available framing metrics, one from Statcast, and one from Baseball Prospectus. The Statcast one looks at all of the pitches near the edge of the zone (called the “shadow”) and assigns the catcher .125 runs for every shadow pitch called a strike (after adjusting for pitcher and park). The Baseball Prospectus one is a little bit more granular on the per-pitch basis for how it assigns credit between catcher and pitcher.

But you don’t have to worry about those nuances because for the first five years of Jansen’s career they tell a similar story. Baseball prospectus has him as 12 runs better than average over that time, and Statcast has him at +4.

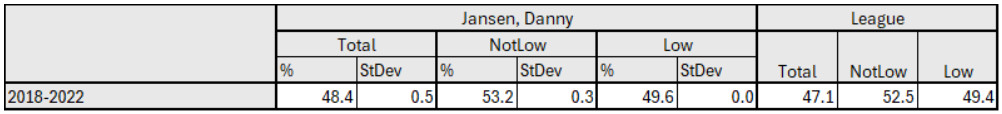

I’ve broken his framing numbers out by zone, basically recreating the Statcast metric without the adjustments. Through 2022, Jansen got called strikes on 48% of pitches in the shadow zone (attack zones 11-19 in a Baseball Savant search), which is half a standard deviation better than the average. He was exactly average on pitches directly below the strike zone (attack zone 18).

Data from Baseball Savant

Perhaps because of that relative weakness in framing low pitches, in 2023 Jansen began to put his left knee down with no one on base and fewer than two strikes. But with two strikes, and with men on base in any count, he kept both knees up.

A few weeks ago, Marc Topkin of the Tampa Bay Times wrote about Jansen’s stance changes. Quoted in that article, Jansen described how important it was to him to be able to block:

“I’m stubborn, and I’ve been around a little bit and I’ve done this,” said Jansen, 29 and in his eighth-big league season. “I’ve been a one-knee guy with nobody on base. But we’re talking about secondary stance, the action stance, I’ve always been (on) two feet.

“I just loved it. I never wanted to give anything up to get something in a way. Whether that was my block-first mentality, maybe that’s the reason I kept doing it.”

Jansen kept this pattern throughout both 2023 and 2024, and this is where we start to get into small sample sizes that make rock solid narratives slippery. For 2023 Jansen was an above average framer, and secured an average strike rate on low pitches. For 2024 he was a below average framer, with a below average strike rate on low pitches. Taken in the aggregate across both years, it’s difficult to see the impact of putting the knee down.

Data from Baseball Savant

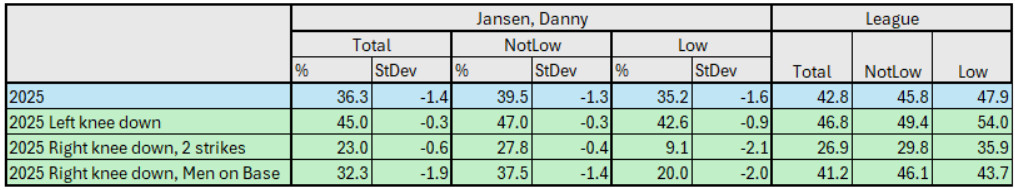

In the above chart I’ve separated Jansen’s framing into three categories: left knee down (bases empty, less than two strikes), knees up (two strikes), and knees up (men on base). Note that the two knees up categories overlap. I didn’t combine them because also note that the league as a whole gets dramatically fewer shadow zone strikes called with two strikes than they do with less than two strikes. This may have to do with pitch selection, with umpire shyness, or maybe some combination of both.

It is not clear from these numbers whether putting his left knee down helped or hurt Jansen’s framing. Across all situations the low strike remained a weakness for him, and during this period that weakness was accentuated relative to his past results, no matter the stance.

Despite those mixed results, Jansen took it a step further this year, his first with the Rays. Again from Topkin:

“I think with Tommy not forcing it but (being) willing to talk about it and experiment with [putting a knee down] and (let me) just try it, finally after a couple spring games I was like, ‘All right, I’m going to do it. I can really see the benefit for me.‘”

Jansen liked how, from a base of his right knee down, he came up in a direct line to throw to second base. He said it kept him from “getting squirrelly” as he sometimes would and rushing his throw.

This is the interesting detail — Jansen putting a knee down isn’t new. It’s WHICH KNEE that’s changed since he arrived in Tampa Bay.

With no one on base and with fewer than two stikes, he now positions himself the same as he did in 2023 and 2024, with his left knee down. But when there are runners on base or the count has two strikes — those situations where last year he stayed in a crouch because he wanted to be ready to block and throw — he now lowers the right knee.

The Best Laid Plans

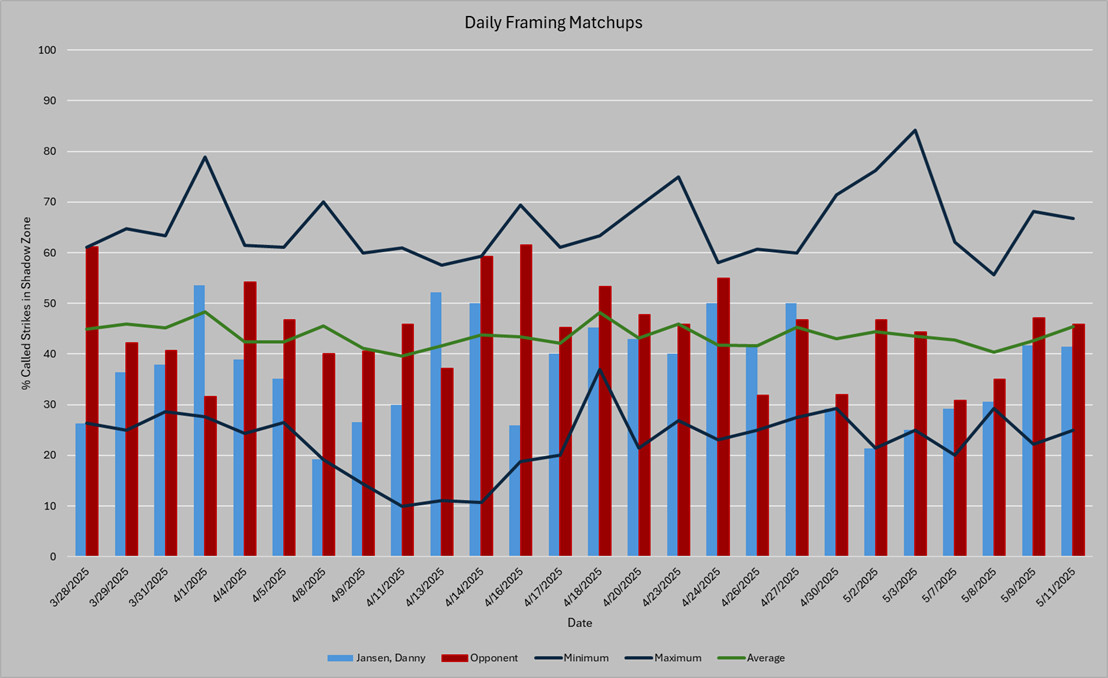

It was reasonable to think that moving Jansen’s setup to rest entirely on a knee would help solve his low strike problems, but so far it’s going about as poorly as it could. By the Statcast framing metric Jansen is 60th out of 61 qualified catchers this year, three runs worse than the average. Baseball Prospectus has him as 32nd out of 35 qualified catchers, 2.2 runs below average. And looking at it through the lens of the matchups with the opposing catcher (to try to control for daily umpire tendencies) it’s just as bad as the overall numbers suggest.

Data from Baseball Savant

Jansen has “lost” to his opposing catcher (meaning the Rays got a lower percentage of pitches in the shadow of the zone called as strikes) in 22 out of 26 games. And he’s recorded the lowest number of strikes of any catcher in the league (minimum 10 pitches in the shadow zone) on four of those days.

Those are bad numbers, and unexpectedly so from a catcher who has generally been average or above throughout his career. But this is where that detail about the right vs left knee comes into play.

Data from Baseball Savant

The major dropoff in Jansen’s framing is almost entirely coming in those situations where he’s dropped his right knee. With the left knee down he’s less than half a standard deviation below average, but worse on low strikes. These are numbers we hoped Jansen could improve on, but they’re in line with his previous career.

But with the right knee down and men on base he’s recorded nearly two standard deviations overall fewer strikes than the average catcher would expect, with that familiar special struggle on the low strike.

So what’s next?

Three runs worse than average over 26 games doesn’t sound like very much, which is a testament to just how excellent framing technique has become across the league, and how difficult it is to fool a modern umpire. The framing floor isn’t low as it once was. And Jansen’s bat has also gotten off to an uncharacterisitcally slow start, sitting nearly four runs below average over this same time period.

But the framing runs are more noteworthy because they seem to be systematic. The lost strikes are disproportionately coming when the right knee goes down, and because of that they’re highly leveraged to run and and win expectancy. Third strikes are the ones that end plate appearances, and runners on base need to be stranded.

At the same time, a systematic problem implies the potential for a systematic fix.

A part of me wonders what would happen if Jansen simply bucked the trend and picked both his knees back up, going back to the setup he used when he graded as an above average framer. But one of the supposed pluses to one knee down catching is decreased wear and tear, and that 24 year old Jansen who was 12 BP framing runs above average in 2019 had a lot less mileage on his knees than the 30 year old Jansen on the Rays now.

Maybe there’s a tweak to his right knee setup that Jansen and Rays catching coach Tomas Francisco can figure to help him get more fluidly to the catch point. While unfortunately there’s no public data to show it, I think Jansen’s catch point is often further back behind the plate than that of some other receivers in the league, which can make it more difficult to present a low strike. And in an article that will post later today, Brian Menendez identified one specific aspect of Jansen’s knee-down setup that doesn’t match that of the league’s best framers.

Or maybe the problem will fix itself as the year goes on and Jansen becomes more comfortable in the setup and more familiar with the Rays pitchers’ stuff. Perhaps from here on out it simply fades into the statistical background noise like so many other findings, leaving us to wonder whether it was ever real in the first place.

A big thank you to Ben Whitelaw who reviewed video of hundreds of pitches spanning multiple years to establish and fact check the catching setups reflected in these stats, and who is consistently a lively and thought provoking partner in a baseball discussion.