Quick Take

On the final day of the Oakland A’s long run in the Bay Area, one of the team’s most iconic figures, cheerleader and longtime Capitola resident Krazy George Henderson, reflects on his long career in the stands and the legacy of his creation, The Wave.

On the day the Oakland Athletics play their final home game in the East Bay before what certainly looks like an ill-fated move to Las Vegas via Sacramento, nostalgia compels A’s fans everywhere to look back in sad fondness to the GOATs of the franchise.

Greatest A’s player? Gotta be Rickey Henderson (but the discussion for second place on that list would be fascinating). Greatest manager: Probably Tony La Russa. Greatest broadcaster: Can anyone touch the erudite hipster, Bill King? Greatest moment: My vote is for the last out of the threepeat, three consecutive World Series titles, 50 years ago this fall, or Scott Hatteberg’s homer giving the A’s their 20th win in a row back in 2002.

Ah, but what about greatest A’s fan?

Hundreds, maybe thousands, could make a good case to be on that ballot. But if it’s purely by popular vote, then the inevitable choice is probably “Krazy George.”

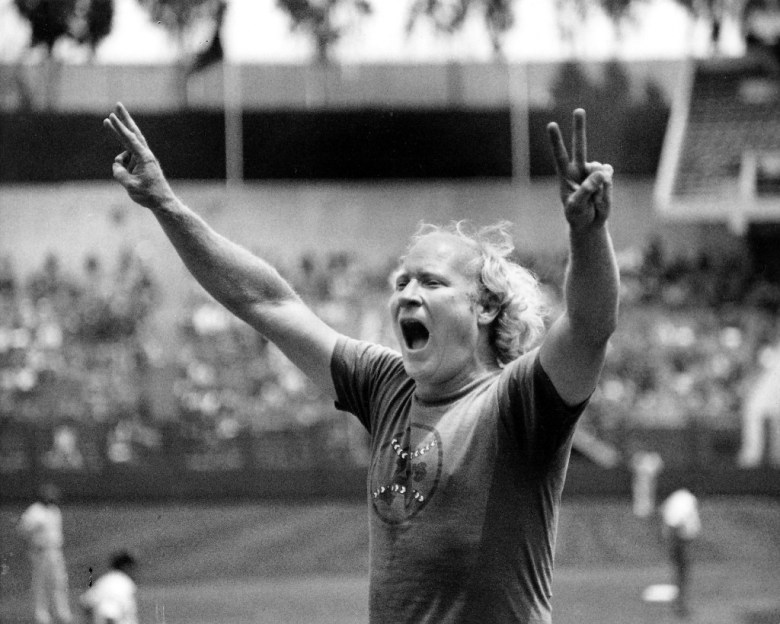

If you don’t recognize the creatively spelled name, you might recognize the image of the snarling, gap-toothed man with the wild blond locks banging a hand drum in cutoffs.

His given name is George Henderson (no relation to Rickey) and he might be one of America’s most iconic sports fans. He’s a professional cheerleader credited with the invention of The Wave, the stadium crowd move that has been delighting, and occasionally annoying, ballpark audiences for generations.

As it turns out, Krazy George is also an icon in Capitola, where he has lived for decades, and where he seemingly has a friend in every bar, restaurant and retail shop in town. On the week that the A’s close up shop in Oakland after 57 years at the Oakland Coliseum, I thought it would be fitting to commiserate with George on this sad occasion.

In fact, George is planning to be at the Coliseum for Thursday’s final home game against the Texas Rangers, a guest of longtime A’s executive Andy Dolich.

“Ah, it’s just so demoralizing,” he said, sitting in his favorite pub, Capitola’s Britannia Arms, which features a framed jersey on the wall as a kind of shrine to Krazy George. “I just feel so bad for Oakland. Every team has left. It’s just so sad.”

For the record, George, who celebrated his 80th birthday last spring, has worked for more than 50 years as a cheerleader for hire, and, in that capacity, has drawn a paycheck from an impressively long list of sports teams throughout North America, from the reigning National Football League champion Kansas City Chiefs to the minor-league hockey team in Yellowknife, Yukon Territory. So, the A’s have no exclusive claim on him. (Of course, Rickey played for eight other MLB teams, too.)

Still, the A’s maintain a special place in George’s sports-fan heart. He’s worked for a half-dozen franchises in the NFL, and just as many in the National Hockey League. He’s riled up crowds for close to 40 minor-league teams. But the Athletics remain the only Major League Baseball team that George has ever worked for. And it was at the Coliseum, while rooting on the A’s in a nationally televised playoff game against the New York Yankees in 1981, that he introduced The Wave to the wider world. On the cover of his 2014 memoir, “Still Krazy After All These Years,” there he is standing on the top of the dugout in the Coliseum, in his trademark golden yellow “Swingin’ A’s” T shirt.

“The A’s are definitely one of my main teams,” he said in that strangled voice which is almost as familiar as his trademark snarl.

“Krazy George” Henderson was hired by the A’s in the late 1970s to revive fan interest in a once-mighty team laid low by free-agent departures. Credit: George Henderson

“Krazy George” Henderson was hired by the A’s in the late 1970s to revive fan interest in a once-mighty team laid low by free-agent departures. Credit: George Henderson

Even before he was “Krazy,” George began his eccentric career way back in the late ’60s while a student at San Jose State University. After graduation, he got a job as a high school teacher in the South Bay, but soon landed a job leading cheers for the California Golden Seals, the long-forgotten first NHL franchise in the Bay Area, based at the Oakland Coliseum Arena. If there’s one sports team that George is more deeply attached to than the A’s, it’s the professional soccer team the San Jose Earthquakes, which hired him for its initial season in 1974, and with which he maintains a relationship to this day (though, technically speaking, today’s Earthquakes are a completely different franchise than the original).

Soon, he landed his first NFL gig with the Chiefs in 1975, an odyssey that took him to the sidelines of the Houston Oilers, New Orleans Saints, Minnesota Vikings and others.

Unlike football, though, baseball has never had any kind of cheerleading tradition, despite the fact that there is so much down time at a baseball game. During the heyday of George’s antics with the A’s, the only other figures in MLB like him were Wild Bill Hagy in Baltimore and the brilliant clown in a bird suit, the San Diego Chicken.

George said he was hired by the A’s in the late 1970s after the franchise had been gutted by infamously cheap former owner Charles Finley, and the new ownership, the Haas family, were looking to reignite interest in a young, rebuilding team (led by a charismatic rookie named, you guessed it, Rickey Henderson).

“That’s why the Haas family, when they saw me and heard about me, [hired me],” he said. “I’ve always thought that they’re not selling sports, they’re selling entertainment, and that’s what the Haas family recognized.”

Already with wide experience in other sports, George had some lessons to learn about the unique challenge of baseball. During his first game with the A’s, he took every opportunity to beat his drum and get the crowd excited. “[At one point], I’m going up in the bleachers like I do at a football game and I’m exhausted. And I turn around and look — it was only the fourth inning. I had to learn how to compensate for baseball.”

The Wave remains Krazy George’s signature move and its popularity with fans of all kinds has endured — I was at a concert at the Greek Theatre in Berkeley in August and I was mildly surprised when The Wave rippled through the audience a few times. People are still doing that?

George said he first started engineering The Wave while working for the NHL’s Colorado Rockies. (Yes, it gets a bit confusing here: The Colorado Rockies are now a Major League Baseball team, but in the 1970s, before the baseball team even existed, the same name was used for Denver’s NHL team.)

The Rockies at the time where a bad hockey team with tiny crowds, and The Wave didn’t really work: “I did The Wave once in a while, and it was really pathetic. There’d be five thousand people, and nobody ever saw it. There was no internet. The team wasn’t televised because they were so bad.”

But when the A’s made the postseason playoffs in 1981 — against the immensely popular Yankees, no less — George had his big audience. Later that year, the University of Washington did something similar at a college football game, but George still lays claim to being the first. After that, he began choreographing The Wave in other venues, including at a soccer game during the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. From there, the craze took on a life of its own. Many soccer crowds throughout Mexico adopted it, and it soon became an international phenomenon.

“Krazy George” Henderson is a familiar face in Capitola Village, particularly at Britannia Arms, which honors him with a framed jersey. Credit: Wallace Baine / Lookout Santa Cruz

“Krazy George” Henderson is a familiar face in Capitola Village, particularly at Britannia Arms, which honors him with a framed jersey. Credit: Wallace Baine / Lookout Santa Cruz

Krazy George expects to be emotional when he visits the Coliseum for the last time on Thursday. He is recognized as a part of the A’s legacy in Oakland, and even has his image painted on a mural on an interior wall at the Coliseum.

He admitted that he doesn’t know what to expect. He hopes that some older fans will recognize him, as they’ve done so many times in recent years, and ask for selfies. But the ushers on hand are, he said, likely not to have any idea who he is or what he represents to A’s fans. Still, he’s proud of his role in developing the A’s fan base, especially during a time when the thrill of the three-time champion “Swingin’ A’s” had faded to sparse crowds.

Sure, it was mostly the exciting young team of the early ’80s that revived the Oakland dream. But Rickey wasn’t the only Henderson to play a role in the dawn of a new era of a franchise that would be world champs again by the decade’s end.

“The fans have always been so good to me whenever I went there,” said George. “I would do games when I would just go as a civilian, leave the drum behind, see a game with my brother. And people were always eager to come up and say hi and remember the old days. I hope I’ll see some fans again, take a selfie or two.”

Have something to say? Lookout welcomes letters to the editor, within our policies, from readers. Guidelines here.