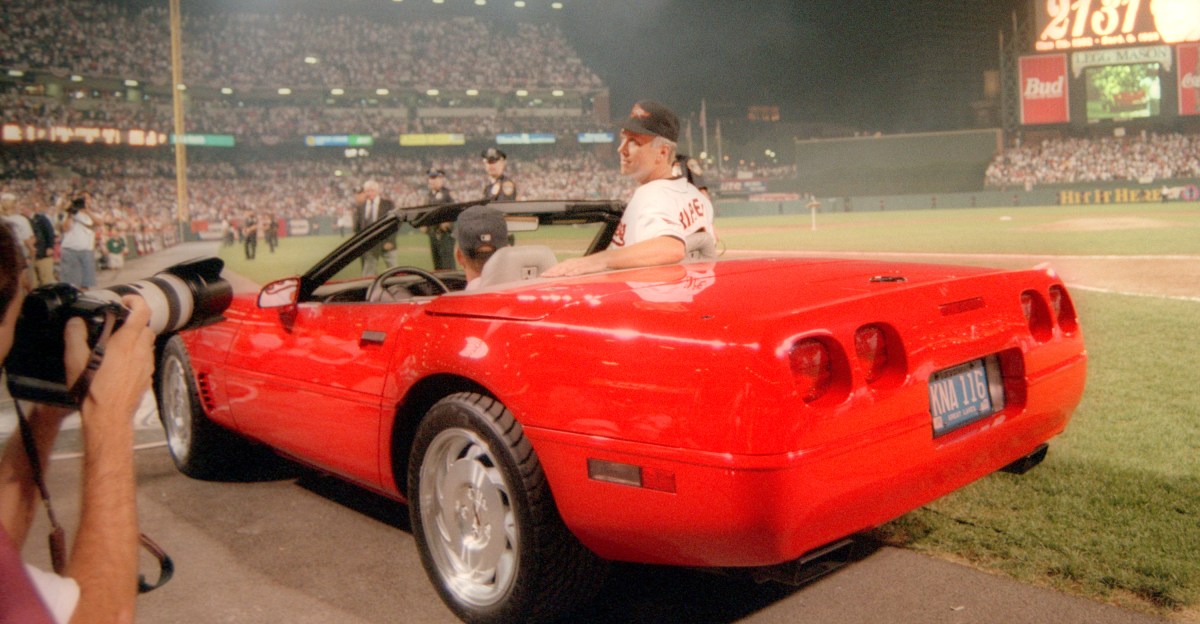

Either Chevy gave him this car as a promotion, or he got to drive his own car into the ballpark that day. (The rest of the time, players have to take the bus.) Photo by Mitchell Layton/Getty Images Getty Images

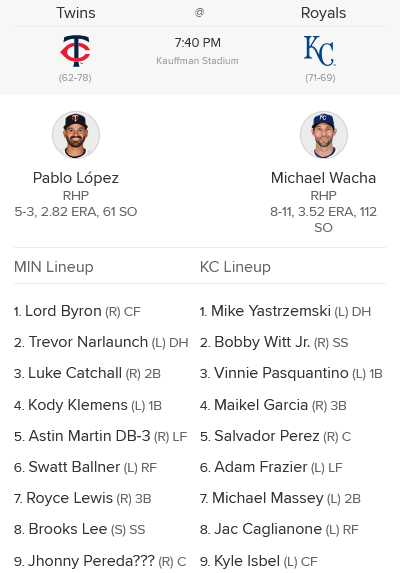

First pitch: 6:40 Central

Weather: National Weather Service somewhat still gutted, chance of showers decreasing, 62°Opponent’s SB site: Royals ReviewTV: Twins TV. Radio: Denny Matthews has been doing Royals games since 1969

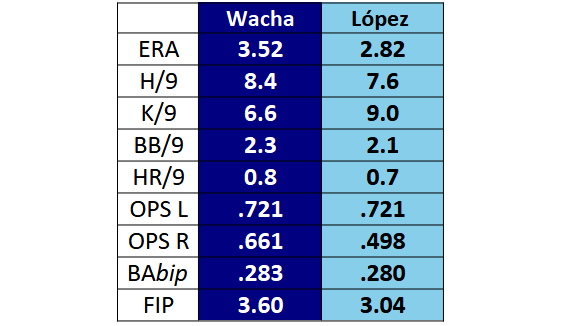

It’s the return of noted aviation enthusiast Pablo López, pitching for the first time since June 3rd. His mound opponent will be Michael Wacha, who’s become a very reliable starter the last several seasons. Wacha is primarily a fastball/changeup sort who throws in the low 90s and will add in a cutter and some breaking stuff. Baseball Savant has his “offspeed run value” at 100. That’s entirely because of the changeup. FanGraphs has it at a 18.2 pitch value, which is HIGH. It’s a good changeup.

I’m including the YTD stats not because they tell you anything about Pablo’s current ability level — he’s just coming back from injury — but because they indicate just how well his first 11 starts had gone. If he hadn’t gotten hurt, would the Twins have still had a giant “going out of business” sale later? Who knows. Will they trade López in the offseason for a player to be born later? Probably. Digits:

I’ve never heard Mr. Denny Matthews on the radio — I’ve never been to Missouri — but 57 seasons calling Royals games on the radio is darned impressive. From the team website, that’s longer than the late, great Bob Uecker in Milwaukee. The only ones longer? Both for the Dodgers. Vin Scully (67 years) and Jaime Jarrín (62 years). Jarrín was originally from Ecuador, and began broadcasting when he was 16! At 19, he arrived in America, and had never seen a baseball game. At age 22, he was hired by Walter O’Malley to broadcast the team’s first L.A. season in Spanish, and did so through 2022.

Matthews was a late bloomer by comparison — 24 when he worked his first Royals game (in their first season as an expansion team). Congrats to him on a great career.

The Royals have a mini-Ohtani. Sort of. Jac Caglianone. He was a two-way player in college. Not a great pitcher, though, merely average. So he hasn’t pitched in the minors or majors. Still, he could be kind of an emergency pitcher if the Royals needed one.

The day, however, goes to a non-Royal or Twin, Cal Ripken. It was 30 years ago today that Ripken officially tied Lou Gehrig’s record of consecutive games played. (The record pursuit sure didn’t hurt attendance any — they were regularly drawing over 40,000 despite being 15+ GB since mid-August.) Our sibling site Camden Chat has a memory post here.

Ripken’s tying (and, the next day, breaking) the record was seen as a huge positive for baseball. Remember, the 1994 season had stopped in August and never restarted, meaning there was no World Series — for the first time since 1904. Ripken, a soft-spoken player with bright blue eyes, was the perfect throwback to when baseball was popular and free from strife. (It was popular — it was NEVER free from strife. The public just didn’t see it / didn’t want to think about it.)

The widespread coverage of the event was also a huge positive for Camden Yards. Already widely-praised on its opening in 1992, the park’s luster had taken a bit of a dent in 1994, when an overloaded escalator lurched and sent scores of people tumbling backwards to the lower deck. 43 were injured.

But Gehrig record was seen all over the country — and not just by baseball fans. I wasn’t even big into baseball at the time, and I saw it live on TV; it made CNN, I believe. The moment the game became official, the scoreboard flashed the number 2130. A scoreboard in front of a picturesque “historic” adjacent warehouse.

Camden Yards opened in 1992. It was first of the “retro” ballparks. The 50s through the 80s had seen the construction of giant “multipurpose” stadiums, suitable for football or baseball, and usually built in the suburbs. (Architecture critic Paul Goldberger called them “concrete doughnuts” in his excellent coffee-table book, Ballpark.) Camden was strictly baseball-only, and meant to suggest the quirky, iconic features of old-timey parks squeezed into downtown locations. (It was built by the architectural film HOK Sport, now Populous, and it was their third MLB stadium — Tropicana Field had opened in 1990, and SomeDumbName had opened for the White Sox in 1991. Those were not a well-received as Camden.)

Camden is now the eighth-oldest stadium in MLB. (Ninth if the Rays ever return to Tropicana.) 23 stadiums, almost all with significant taxpayer funding, have been built since. The A’s are playing in a Sacramento stadium built in 2000, and while they have a lot of taxpayer money lined up for their preferred destination in Vegas, they don’t have nearly enough private investment, yet — and John Fisher won’t/can’t spend his own money to make up the difference.

(Does that math seem off? It’s because the last Texas stadium opened in 1994. And closed in 2020. That’s a longer life than Turner Field, 1997-2016.)

I recently read a very good 2022 article by The Ringer’s Dan Moore which sums up the legacy of Camden Yards accurately. In the old, pre-free-agency era of baseball, owners made money by exploiting the players. Now they make it by exploiting taxpayers.

Keep in mind that the Orioles themselves were threatening to leave Camden unless they got handed a giant pile of new taxpayer money. Which they got; at least $600 million in “renovation” money (it could go much higher). Plus a real estate deal giving them the exclusive right to develop property nearby (like that historic warehouse) that lasts 99 years.

Meanwhile, of the other “classic” stadiums, the Guardians, White Sox, and the Royals have all made noise about wanting new buildings. The mayor of Anaheim even went to jail for his role in accepting a bribe in trying to give the team a new building. Toronto’s owner would probably love one, but baseball is not eager to have the sport leave Canada, and Toronto/Ontario are not likely to give him one on typical American terms.

As Moore describes, this all really began after 1984. When Baltimore Colts owner Robert Irsay, literally under cover of darkness, moved the team from Baltimore to Indianapolis. Prior to that, when the Orioles demanded a new stadium, mayor William Schaefer had said, “Unless private enterprise builds it, we won’t build it.” Three years after the Colts left, the financing for Camden was passed.

This has been the threat ever since. New stadiums —- with ever-shorter lifespans and ever-growing additional real estate to develop — or the team will leave town. Your Major City will suddenly become a Minor One.

Which is ridiculous. No team ever got hurt by a sports team leaving. It hurts the fans, sure — there are still people who ache over the Dodgers moving to L.A. But it doesn’t hurt the city.

The Seattle SuperSonics played in Key Arena for the better part of 40 years, and when they hosted the Portland TrailBlazers, would frequently play in the Kingdome. Demand for tickets was that big. They went to the NBA Finals four times, winning once. My brother once played Pop-A-Shot in a Portland bar with Gary Payton and beat him about half the time. (My brother could not have beaten Gary Payton once in an actual game of one-on-one. Not if they played 1000 times.)

The Sonics left for Oklahoma City in 2009. Is Seattle a second-class city today? It is not.

Do new stadiums generate economic growth? Almost never. There’s been some in San Francisco (where private funds paid for almost all of the Giants’ stadium) and some in Sacramento (where private funds paid for most of the NBA Kings’ arena). Public money spent on these things is a waste. And, because people have a limited amount of entertainment money, when it goes to spending on a game, it’s not going to restaurants & such elsewhere. During the NHL lockout of 2004-2005, Toronto businesses reported sales going up because there was no hockey.

And, keep in mind that now team owners want all the land around stadiums for restaurants and fancy condos and such. That’s money that would have gone to many local business owners, now going entirely to one. One who’s likely to spend that money on other investments, not on buying things from local businesses.

So it was nice when nice guy Ripken tied Gehrig’s record. But the legacy of Camden’s shining moment has been scuffed up quite a bit since. Not Ripken’s fault, and not that particular stadium’s fault. But the way every owner in baseball began demanding to one-up the last new building. And the way nearly every politician caved. Sports owners are like spoiled children; they will never stop whining for more toys. And just like spoiled children, they sulk when they can’t get a new one. Which is what the Twins’ owners are doing right now.