This isn’t some gobsmacking revelation about baseball, but when you throw a fastball right down the middle, bad things tend to happen. Unless you throw 100 miles per hour and have electric movement, those pitches tend to get crushed—and even then, batters will sometimes sit on that offering and hit it hard somewhere. Matthews has allowed a .612 slugging average on heaters this year, despite a fairly lively pitch with two-plane movement and an average velocity north of 96 miles per hour.

The problem is location. Matthews has great control, but he hasn’t always had good command of his four-seamer within the strike zone. When you look at where he locates that pitch, it’s not as much of a mystery that it tends to get hammered. Let’s look at where he throws his heaters and where he has the most success with them, side-by-side, to illustrate the point. First, for righty batters:

(16).png.4f2cdabea1c83f67596d9a7d807fc333.png)

Whenever he can put the fastball on the top rail or along the outer edge of the plate, he does well with it. The pitch has more ride than the hitter would expect, based on Matthews’s arm angle, and it also runs more to his arm side than his delivery suggests. That leads to righties sometimes giving up on a fastball away and taking a called strike, and to guys swinging under those balls at the top of the zone. Matthews gets into trouble, by contrast, when he ends up throwing the heater right down the middle, or in but belt-high. Those aren’t unusual places for a pitcher to get hurt. What’s unusual is that Matthews leaves such a glaring percentage of his heaters in the heart of the zone. You can see that he’s trying to go up and away from righties, but he’s ending up throwing far too many pipeshots.

Part of the problem is that that natural arm-side movement works against his efforts to attack that upper and outer quadrant, rather than for them. Pitchers who can drill the upper, glove-side portion of the zone with their fastball drive hitters crazy (Chris Paddack talked to us about why it’s such a staple of his arsenal back in April), but most of them can do that because they throw from a fairly high arm slot and/or have a fastball that cuts more than most four-seamers. Matthews’s, by contrast, runs more than most similar pitches, so the tendency is for that ball he’s aiming at the outer edge to wander over the meaty part of the dish—like this:

WU9reTdfVjBZQUhRPT1fVUZSVUFRVUdWUVVBQ2dBQkJBQUhBbE1GQUFBTlVsZ0FDMWNBQ1FKVUJsZFhCVk5l.mp4

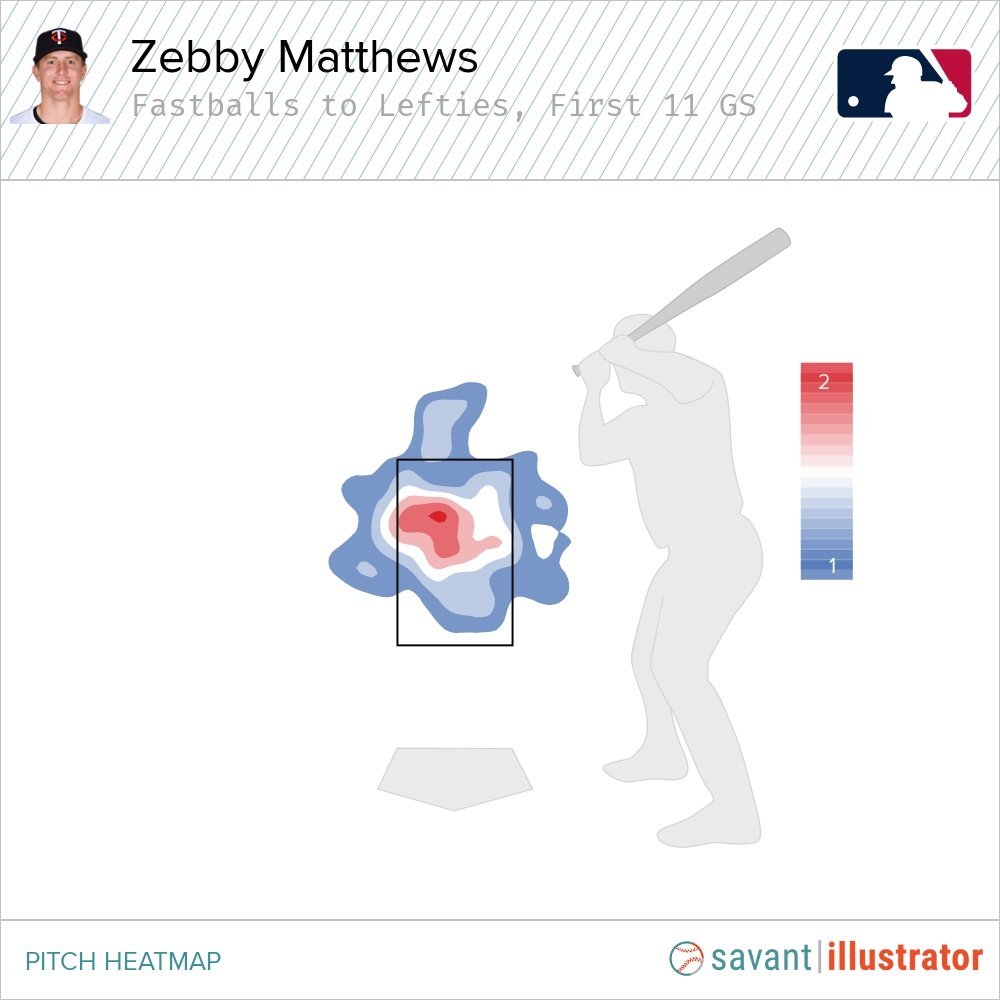

The story is slightly different against lefties, but the broad strokes are similar. Matthews still has success at the top of the zone and on the glove side, but he still throws too many of the things right down the middle, where success is almost impossible.

(17).png.86104999e1189d90aa4074b10dd3b8ee.png)

As you can see, Matthews fares well almost everywhere but the center of the zone when throwing his fastball to lefties. This is where the deceptive run on that pitch comes into play for him. That the offering has horizontal movement a bit like a sinker but rides like a four-seamer gets a lot of lefties reacting oddly to it. He seems to be throwing it right at them, and they can read and adjust to the vertical movement, but they pull their hands in too far and hit lazy flies on balls down and in (which is usually a lefty’s wheelhouse), not expecting it to tail back onto the plate instead of getting in on their hands.

That only works, though, when he executes and gets that pitch down and in, or keeps it up on the top line of the zone. Just as he has against righties, Matthews has too often ended up leaving the pitch out over the middle of the plate to lefties.

All of that is changing, though. Two starts ago, between his outing in Chicago and one at home against San Diego, Matthews slid over on the rubber. Instead of starting in the middle of the pitching plate, he now sets up on the first-base side. Here’s a game-by-game chart of his average horizontal release point. As you can see, he moved over to that place in the center of the mound after returning from his shoulder injury this summer, but now, he’s back where he started the season—and maybe even a hair farther toward first base.

.jpeg.2ef8008ee75b737fcc8e55f8580e51f4.jpeg)

That’s made a huge difference in Matthews’s ability to attack the glove-side edge of the plate. Here’s where his fastballs to lefties went over all his starts prior to the last one in August:

Here’s where those pitches have gone to those batters over his last two outings.

Being more aligned with the inside edge to lefties (and the outside one to righties) means Matthews doesn’t have to be quite as fine to locate there. Instead of coming back to the heart of the plate, a pitch with the same shape can come back from off the corner to a perfect location for called strikes.

ZFh6M2pfWGw0TUFRPT1fQlFCVUJWTldWQVVBQzFRRFVRQUhCUU1DQUFCUlZsSUFWbHdEVmxKV0F3TUhCbFpX.mp4

When he does want to elevate, meanwhile, he can cut it loose and find the upper arm-side quadrant a bit more easily. Like this:

ZFh6M2pfWGw0TUFRPT1fRGxkV1hWRU5BZ2NBWEFNR0J3QUhCRkJRQUZoVFVGTUFBMU1OVWdjTVVGSldCd3BV.mp4

Matthews is a better pronator than supinator, meaning that (although he’s found a feel for two breaking balls and a cutter) he doesn’t get the ball moving much toward the glove side. His breaking stuff all works more vertically than horizontally, and his four-seamer, sinker and changeup have considerable arm-side run. Moving to the side of the mound that gives his stuff more room to work in that direction (and that keeps him out of the middle of the plate better, with all his pitches) just makes good sense.

In these two outings, Mstthews has worked 12 total innings, striking out eight, walking two, allowing 10 hits, and yielding just three earned runs in total. He might still run into home-run problems in the future, given the nature of his stuff and the imperfect feel he has for some of it, but this was an important shift for him. It should lead to less hard contact from opponents and, in the long run, a series of other benefits.