When Will Warren made his debut in 2024, there were flashes of brilliance scattered across his six appearances, but mostly we saw a rookie pitcher struggling to adjust to the huge leap from Triple-A to the majors. It was much of the same story across his first seven starts this season as injuries to Gerrit Cole, Luis Gil, Clarke Schmidt, and Marcus Stroman pressed the Yankees’ top pitching prospect into service in the MLB rotation. The 34 strikeouts in 28.2 innings proved that the stuff played in the bigs, but struggles with walks, home runs, elevated pitch counts in the early innings, and exposure the second time through the order converged to produce a 5.65 ERA and just over four innings per start.

There are signs lately that he may be rounding a corner. He has now stacked back-to-back strong starts — a career-high 7.1 innings of one-run ball against the Athletics followed by five innings of two-run ball with a career-high nine strikeouts last time out against the Mariners. He walked just one batter in each of those contests and didn’t surrender any home runs. Much of this owes to Warren trusting the fastball more and gaining confidence to throw it in the zone. However, it’s the curveball — a pitch he scrapped in the minors before reintegrating it into his arsenal this spring training — that caught the eye against the Mariners, racking up four strikeouts and a 63-percent whiff rate, earning him a spot on Sequence of the Week.

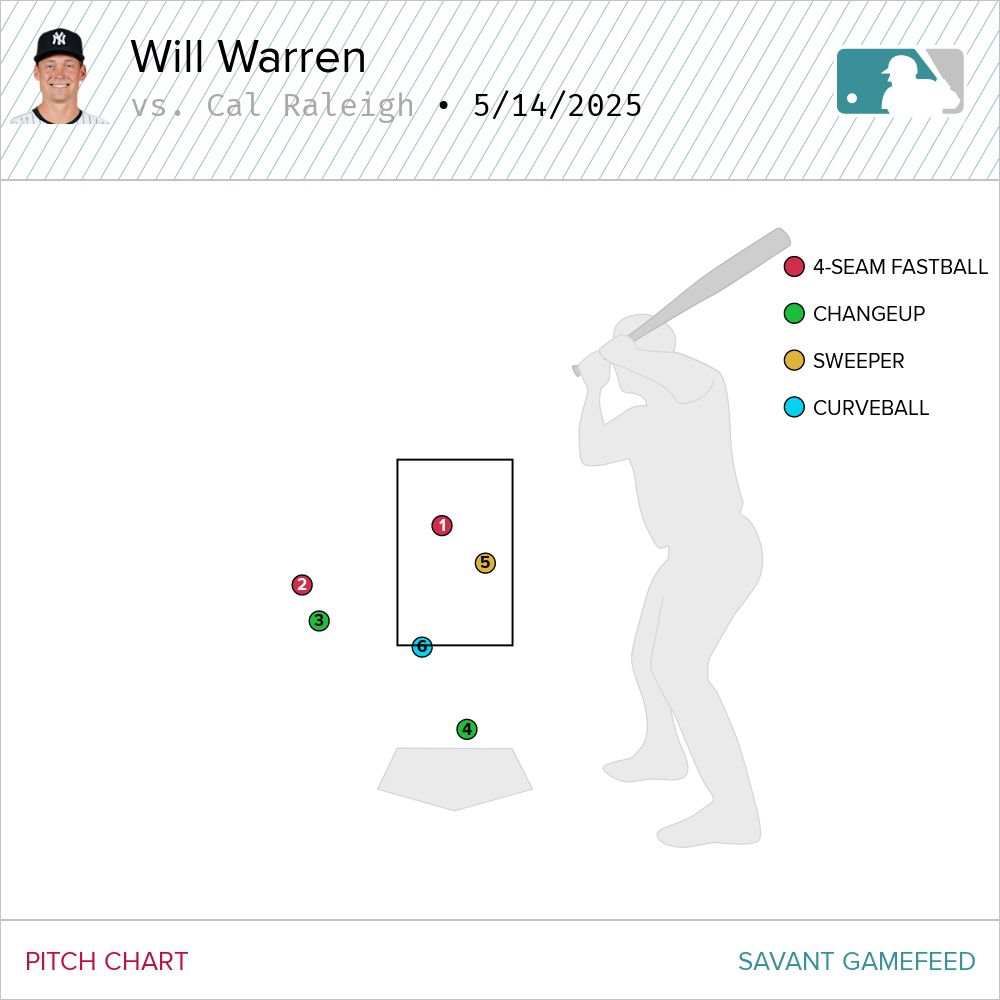

We join Warren with no outs in the bottom of the second of a 0-0 game facing probably the best catcher in baseball in Cal Raleigh. Warren starts Raleigh off with a first pitch four-seamer at 93 mph.

This pitch is pretty much right down the pipe. However, Raleigh almost seems surprised to see a first-pitch heater given Warren’s affinity for the sweeper, and the resulting late swing fouls the pitch back to the screen.

Seeing the late swing, Warren doubles up on the fastball hoping to again catch Raleigh off guard.

Warren’s most common miss with the fastball is arm-side and that’s exactly what happens here. He has a tendency to open his front shoulder a touch early when trying to command the fastball to the arm-side half of the plate, causing the pitch to sail high and wide, and this pitch misses outside by almost a full plate’s width.

After two straight heaters, Warren changes speeds to the changeup. It’s his most trusted pitch against lefties, and after setting Raleigh’s sights away with the previous pitch, Warren attempts to command it to the target he intended to hit with that last fastball.

It’s another miss off the plate away, Warren once again opening that front shoulder a bit too early.

Warren sticks with the changeup for his 2-1 pitch, perhaps hoping that Raleigh is hunting the fastball after the missed execution of the last pitch.

Warren keeps that front shoulder closed this time and gets the ball over the plate, but he tugs this pitch as he tries to mirror the arm speed of the fastball and it ends up below the zone for ball three.

Now that Raleigh has worked himself into a hitter’s count, you have to believe that he is sitting heater. Warren doesn’t give in, instead opting for a get-me-over sweeper to get back in the count.

That’s just what he does, pouring this pitch over the heart of the plate for called strike two. You can see that Raleigh is not expecting a breaking pitch and is unable to trigger his swing by the time he realizes the meatball that Warren left down the middle. For a hitter sitting fastball, out of the hand this looks like a heater that will sail wide for ball four, which is probably why he gives up on the pitch.

Warren has battled back to work the count full. A walk isn’t the worst outcome in the world facing this particular hitter, so there’s no need to give in a groove a fastball. Instead, Warren has license to pursue the strikeout, and he unleashes by far his best pitch of the encounter to punch Raleigh out.

This is the definition of a nasty curveball. Warren starts the pitch right off the outside edge of plate, and it hovers in the zone for most of its path toward the batter before plummeting below Raleigh’s flailing bat.

Here’s the full sequence:

Courtesy of Baseball Savant

I’d like to pay special attention to the interaction between the final two pitches of the at-bat. Warren throws the sweeper and curveball out of an almost identical release point, and the two pitches tunnel for an impressive amount of time before diverging at the last second, ultimately landing a foot-and-a-half apart.

See how the two pitches pass through the exact same spot right at the hitter’s swing decision point? Even if the hitter correctly diagnoses breaking ball as the curveball leaves Warren’s hand, there is still a wide area of the zone they need to cover based on the divergent movement profiles of the sweeper and curveball. This looks like a carbon copy of the pitch Warren threw for strike two, but whereas the sweeper ended up down Broadway, the curve lands below the zone away.

This sweeper-curveball sequencing encapsulates how important it is for a starting pitcher to throw two different breaking pitches. We’ve seen the way that Gerrit Cole and Carlos Rodón have closed the gap between slider and curveball usage and how Max Fried and Clarke Schmidt mix-and-match their sweepers and curveballs. The differential in speed of the curveball from the rest of one’s arsenal creates a wider velocity band that hitters have to account for while the divergence in movement between slider/sweeper and curveball makes it difficult to judge final pitch location even upon successful identification of breaking ball out of the pitcher’s hand.

Finally, the curveball gives Warren a real strikeout weapon against lefties alongside the changeup given it does not suffer the same platoon disadvantage as a sweeper. The curve is certainly a pitch to monitor as Warren’s season progresses and is a tool that I think can give him staying power in a major league rotation.