Tommy John, the man who inspired a million elbow surgeries, was the one who broke the news to Gavin Osteen, albeit indirectly: He was going to the major leagues.

Finally, after nearly a decade in the minors, an illness that scuttled a previous call-up and a shoulder injury that cost him nearly two seasons, Osteen’s time had arrived.

John delivered the news in his guise as a New York Yankees’ television analyst, during a day game against the Orioles, right before the 1998 All-Star break. By then, he was far removed from his 26-year career as a major league pitcher, much less the “Eponymous Medical Procedure” (as described by baseball-reference.com) he underwent in 1975. Tommy John Surgery has since become the preferred method of repairing the ulnar collateral ligament in the elbows of overtaxed hurlers.

But that July day in 1998, John said on the air that Osteen, then a 28-year-old left-handed pitcher, would soon be promoted from Baltimore’s Triple-A affiliate in Rochester, New York, to the bigs. It no doubt resonated with John, since he had been close with Gavin’s dad, Claude, when the two of them pitched for the Dodgers in the early ’70s. It also made sense, since the Birds, 38-50 and going nowhere, were ready to clean house.

The younger Osteen happened to be watching the telecast before heading to the ballpark for a Red Wings game.

“That’s the first I heard of it – on TV,” the Annville-Cleona graduate said recently.

He remembers arriving in the clubhouse, and that the pitching coach, Larry McCall, was “kind of looking at me … out of the corner of his eye to see if I knew anything.”

“And I kind of did, but I wasn’t going to say anything,” Osteen said.

Finally, McCall approached.

“You’re going up to the big leagues at the All-Star break,” he told Osteen.

Only he wasn’t. Gavin would later learn that Ray Miller, the Orioles’ first-year manager, asked team owner Peter Angelos to keep the club’s nucleus together a little longer, just to see if the Birds could turn things around. And they did for a time, winning nine in a row and 14 of 15 after the Break to creep above .500. They topped out at 68-58 in mid-August, and while they sagged late in the season, finishing just 79-83, Osteen’s call never came.

And it never would.

The ace of A-C’s 1986 state championship team, he pitched professionally for 13 years in all (1989-2002), going 64-59 with a 4.01 ERA. In four of those seasons, he was employed at the highest level of the minors. Now 55 and a coach and instructor locally, he long ago came to grips with the fact that the majors proved to be a bridge too far.

“I’ve got nothing to complain about,” he said. “This game, it’s about being in the right place at the right time.”

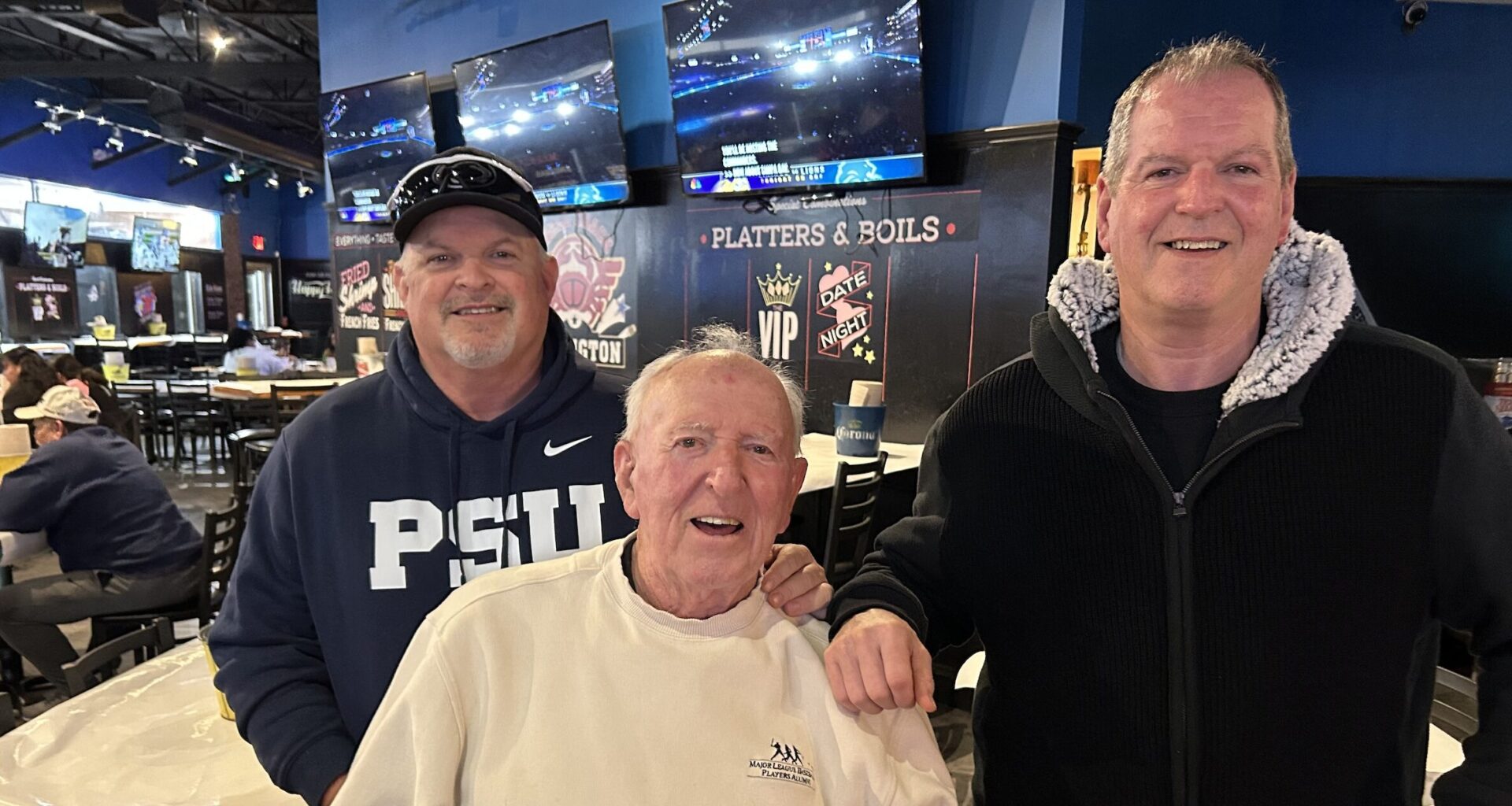

Gavin’s older brother Dave, 62, long ago reached the same conclusion. Like Gavin, he pitched for the Dutchmen, leading them to a Lancaster-Lebanon League title in 1981. And like his younger brother, Dave, a right-hander, competed at Triple-A, in the St. Louis Cardinals’ organization.

But he also hit a glass ceiling, despite going 54-30 with a 3.43 ERA in six minor-league seasons, including 15-5 at Double-A Arkansas in 1989. The next season, he was also doing well at Triple-A Louisville, going 5-2 with a 3.42 ERA, and he remembers his roommate, former major league reliever Ernie Camacho, telling him he deserved a call-up.

Dave Osteen pitches for Arkansas, a Double-A affiliate in the St. Louis Cardinals’ chain. (Provided photo)

Dave Osteen pitches for Arkansas, a Double-A affiliate in the St. Louis Cardinals’ chain. (Provided photo)

Dave Osteen pitches for Arkansas, a Double-A affiliate in the St. Louis Cardinals’ chain. (Provided photo)

Dave Osteen pitches for Arkansas, a Double-A affiliate in the St. Louis Cardinals’ chain. (Provided photo)

“I wasn’t the type who would say anything, but in my mind, I go, ‘Yeah, he’s right,’” Dave said. “So it got my hopes up a little bit, and sure enough, Sept. 1 came, and they called about five guys into the manager’s office, and I wasn’t one of them. It really crushed me.”

But baseball always demands that the page be turned. And so it is with Dave, who serves as a pitching instructor in the Dallas/Fort Worth area and lives near his 86-year-old father, who pitched in the majors for 18 years and served as a pitching coach for 15.

“I’ve come to grips with it,” Dave said. “I wish I’d have gotten at least a chance, because of the way that I pitched, and because of the type of pitcher I became.”

Which is to say, a guy who didn’t throw hard – his fastball topped out at 89, 4 mph slower than Gavin’s – but could hit his spots, pitch to contact, and put his defense to work. And if his inability to light up a radar gun worked against him, so too did his age. He began his professional career at 22, which is old for someone in the low minors, after three years at Elon and two at Oklahoma State.

So he knew the score then, and still does now.

“It will kill you,” he said, “if you sit there and dwell on all that.”

At least the Osteen brothers, the oldest and fourth-oldest of five children born to Claude and his first wife Georgie, have their memories to sustain them. Gavin recalls starting A-C’s victory over Salisbury in the ’86 state semifinals and closing its title-game victory over Ford City. He also preserved the victory in the semis with a diving catch in center field.

Good times. But what made that stretch even better – what made it “the greatest time in (his) life,” as he put it – was accompanying his dad, the Phillies’ pitching coach from 1982 to ’88, to Veterans Stadium on game day. They would arrive hours before first pitch, and the way Gavin tells it, find one player awaiting them in the clubhouse – Pete Rose.

Gavin acknowledges that Rose is a “controversial” figure, but he would already be in uniform, chomping at the bit.

“And he’d be like, ‘Let’s go, let’s go. We’re going out,’” Gavin said.

They would head out to the field, and Rose would put the younger Osteen through his paces. Same for whatever friend he might have in tow. They would take some swings, take some grounders, soak up any pointers the self-proclaimed Hit King might have to offer.

Rose departed after the ’83 season, which saw the Phillies fall to the Orioles in the World Series. And still Gavin and his buddies headed down to the Vet. They would, he recalled, play Home Run Derby from second base – “and knock out the bulbs of the PhanaVision,” the video screen perched beyond the outfield fence.

Dave, for his part, remembers playing winter ball in Venezuela before boisterous crowds. After one controversial road victory, his team, which included major leaguers Omar Vizquel and Tony Armas, hurried to their bus as the home fans bombarded them with anything they could get their hands on.

“The bus driver takes off, and it’s like Clint Eastwood in ‘The Gauntlet,’” Osteen said. “He’s slamming into parked cars, and they’re throwing stuff at the bus. They broke out every window in the bus.”

As for Gavin, he remembers falling ill just as Oakland called him up from Triple-A Tacoma in 1994.

Gavin Osteen during his time in the Oakland Athletics’ chain. (Provided photo)

Gavin Osteen during his time in the Oakland Athletics’ chain. (Provided photo)

“I tried to fight it, and I tried to hide it,” he said.

To no avail. That opportunity passed. Then he tore the labrum in his pitching shoulder, and appeared in exactly one game in 1995 and none in ’96. He worked his way back and spent four more years in affiliated ball, then mostly played independent ball his final three.

Dave wrapped up his career in 1991. And, he said, “The first thing I wanted to do was go to the beach, because I had spent every summer of my life playing baseball.”

So he bartended in Bethany Beach for two years, and in Northern Virginia for one. Then he embarked on a coaching career that took him to Florida, Australia, Bridgeport, Conn., Purdue University, and finally, High Desert, the Milwaukee Brewers’ affiliate in the Class A California League.

He spent the 1999 season at that last stop before the Brewers jettisoned the entire staff. Fine with him.

“I didn’t like the moving around,” he said. “I always wanted a dog, and with a minor league schedule, you couldn’t have a dog.”

He has had three pups since then, while settling into an area that, for whatever reason, has a massive demand for pitching instruction. Dave usually works with hurlers between the ages of 8 and 18, though he also counts a 70-year-old among his mentees.

“He is a pilot, and he plays in an over-70 league in Arizona,” he said. “I guess he’s based in Dallas, and whenever he’s here, he comes to me to prepare for his next season. And he throws it pretty good for 70.”

Gavin has worked with the Midstate Mavericks, a cluster of age-group travel teams, since 2000, and Future Stars Tournaments, which organizes baseball events, since 2005. He also coaches the Palmyra Orioles, a fall-ball team.

Meantime, he has seen one son, Derrick, play at Cedar Crest and William & Mary. Another son, Nate, played at Palmyra through last spring and plans to do the same at Penn State-Altoona.

The game remains the thing. It’s part of Gavin and Dave’s DNA, an integral part of their lives. It didn’t take them to its highest heights, and if that once stuck in their craws, that is no longer the case. After all, time heals all wounds. Heals them as readily as a certain Eponymous Medical Procedure.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Support Lebanon County journalism.

Cancel anytime.

Still no paywall!

Fewer ads

Exclusive events and emails

All monthly benefits

Most popular option

Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Quality local journalism takes time and resources. While LebTown is free to read, we rely on reader support to sustain our in-depth coverage of Lebanon County. Become a monthly or annual member to help us expand our reporting, or support our work with a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.