Wednesday concludes Hispanic Heritage Month. It began Sept. 15, the same day MLB celebrates Roberto Clemente Day.

Clemente died on Dec. 31, 1972, when the plane he chartered to deliver relief supplies to victims of the Nicaraguan earthquake crashed into the ocean less than two miles from the Puerto Rican coast.

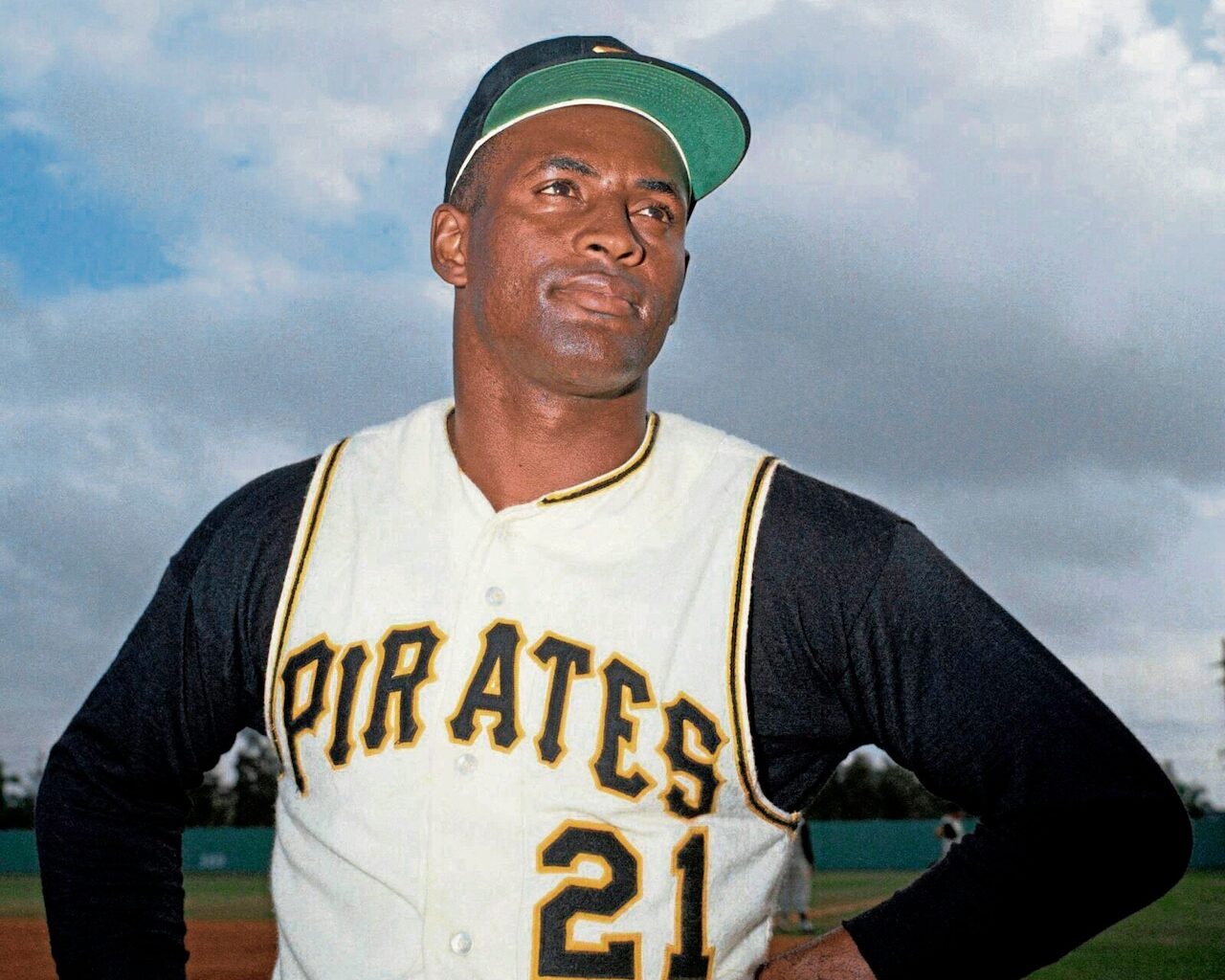

The record book will tell you that Roberto Clemente collected 3,000 hits during his major-league career. It will say that over 2,433 games, he came to bat 9,454 times and drove in 1,305 runs over 18 years.

But it won’t tell you about Carolina, Puerto Rico, and the old square. And the narrow, twisting streets, and the roots that produced him. It won’t tell you about the Julio Coronado School and a remarkable woman named Maria Isabella Casaresi whom he called “Teacher” until the day he died and helped to shape his life in times of despair and depression. It won’t tell you about a man named Pedrin Zarrilla, who found him on a country softball team and put him in the uniform of the Santurce Crabbers and nursed him from a promising young athlete to a major-league superstar.

And most of all, those cold numbers won’t begin to delineate the man Roberto Clemente was. To even begin to understand what this magnificent athlete was all about, you have to work backward. The search begins at the site of its ending.

The Newark Star-Ledger sent me to Puerto Rico a month after he died on a mission of discovery. Baseball is a game of statistics and fan loyalty and marvelously talented athletes. That combination is the formula that passes love of the game and love of its heroes from family generation to family generation. We all knew the numbers, but I went there in search of the man.

Pittsburgh, where Clemente had become a legend, had a Latino population of no more than 1% when he arrived. Yet here came a brown-skinned Latino-born migrant who would win the hearts and baseball soul of what had been a blue-collar factory town – a city that had few folks who looked like him and even fewer with his accent.

I went to his island in search of an answer to a question that few people who so admired him knew. What really shaped their most admired hero?

The quest began on a pre-dawn street in search of a place colloquially known as Punta Maldinado. The paved street turns down a bumpy secondary road and moves past small shantytowns. Then there is another turn onto hard-packed dirt and sand, and although the light has not yet quite begun to break into pre-dawn, you can sense the nearness of the ocean. You can hear its waves, pounding harshly against the jagged rocks.

You can smell its saltiness. The car nosed to a stop, and the driver said: “From here you must walk. This is the nearest place. This is where they came by the thousands on that New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day. Out there,” he said, gesturing with his right hand. “Out there, perhaps a mile and a half from where we stand. That’s where we think the plane went down.”

The final hours of Roberto Clemente were like this:

Just a month earlier, he had agreed to take a junior-league baseball team to Nicaragua and manage it in an all-star game in Managua. He had met people and made friends there. He was not a man who made friends casually. He had always said that the people you wanted to give your friendship to were the people to whom you had to be willing to give something more — no matter what the price.

Just two weeks after he returned from that trip, Managua, Nicaragua, exploded into flames. The earth trembled, and five people died. It was the worst earthquake anywhere in the hemisphere in a long time.

Back in Puerto Rico, a television personality named Luis Vigereaux heard the news and was moved to try to help the victims. He needed someone to whom the people would listen, someone who could say what had to be said and get the work done that had to be done and help the people who had to be helped.

“I knew,” Luis Vigereaux told me, “that Roberto was such a person, perhaps, the only such person who would be willing to help.”

And so the mercy project, which would eventually claim Clemente’s life, began. He appeared on television, but he needed a staging area. The city agreed to give him Sixto Escobar Stadium.

“Bring what you can,” he told the people. “Bring medicine … bring clothes … bring food … bring shoes … bring yourself to help us load. We need so much. Whatever you bring, we will use.“

And the people of San Juan came. They walked through the heat, and they drove old cars and battered little trucks, and the mound of supplies grew and grew. Within two days, the first mercy planes left for Nicaragua.

Meanwhile, a ship had been chartered and loaded. And as it prepared to steam away, unhappy stories began to drift back from Nicaragua. Not all the supplies that had been flown in, it was rumored, were getting through. Puerto Ricans, who had flown the planes, had no passports, and Nicaragua was in a state of panic.

“We have people there who must be protected. Black-market types must not be allowed to get their hands on these supplies,” Clemente told Luis Vigereaux. “Someone must make sure — particularly before the ship gets there. I’m going on the next plane.”

The plane they had rented was an old DC-7. It was scheduled to take off at 4 p.m. on Dec. 31, 1972. Long before takeoff time, it was apparent that the plane needed more work. It had even taxied onto the runway and then turned back. The trouble, a mechanic who was at the airstrip that day conjectured, “had to do with both port engines. We worked on them most of the afternoon.”

The departure time was delayed an hour, then two, then three. At 9 p.m., even as the first stirrings of the annual New Year’s Eve celebration were beginning in downtown San Juan, the DC-7 taxied onto the runway, received clearance, rumbled down the narrow concrete strip, and pulled away from the earth. It headed out over the Atlantic and banked toward Nicaragua, and its tiny lights disappeared on the horizon.

Just ninety seconds later, the tower at San Juan International Airport received this message from the DC-7 pilot, “We are coming back around.”

Just that.

Nothing more.

And then there was a great silence.

“It was almost midnight,” recalls Rudy Hernandez, a former teammate of Clemente’s, “We were having this party in my restaurant. Somebody turned on the radio, and the announcer was saying that Roberto’s plane was feared missing. And then, because my place is on the beach, we saw these giant floodlights crisscrossing the waves, and we heard the sound of the helicopters and the little search planes.”

Drawn by a common sadness, the people of San Juan began to make their way toward the beach, toward Punta Maldonado. A cold rain had begun to fall. It washed their faces and blended with the tears.

They came by the thousands, and they watched for three days. The government sent a team of expert divers into the area, but the battering of the waves defeated them as well.. Midway through the week, the pilot’s body was found in the swift-moving currents to the north. On Saturday, bits of the cockpit were sighted.

And then — nothing else.

Rudy Hernandez told me, “I have never seen a time or a sadness like that. The streets were empty, the radios silent, except for the constant bulletins about Clemente. Traffic? Forget it. All of us cried. All of us who knew him and many of those who didn’t, wept that week. There will never be another like Roberto.”

This series will continue on Tuesday

If you purchase a product or register for an account through a link on our site, we may receive compensation. By using this site, you consent to our User Agreement and agree that your clicks, interactions, and personal information may be collected, recorded, and/or stored by us and social media and other third-party partners in accordance with our Privacy Policy.