Narratives abound in October. Often, these are baseballisms handed down from announcer to announcer, such as “players need to bunt more” and “small ball wins playoff games”, and their accuracy can waver depending on how nostalgic the source is feeling. One that consistently arises, though, is that relievers are pitching more than ever in October with each successive season.

Logically, this tracks. Teams are smart, maybe too smart, and have realized several things. Firstly, starting pitchers pitch better in shorter stints; they can max out a bit sooner and don’t have to face the three time through the order penalty. Secondly, relievers generally perform better than starters, as they can rip off nasty breaking balls and high-octane fastballs in short bursts without remorse. But is it true?

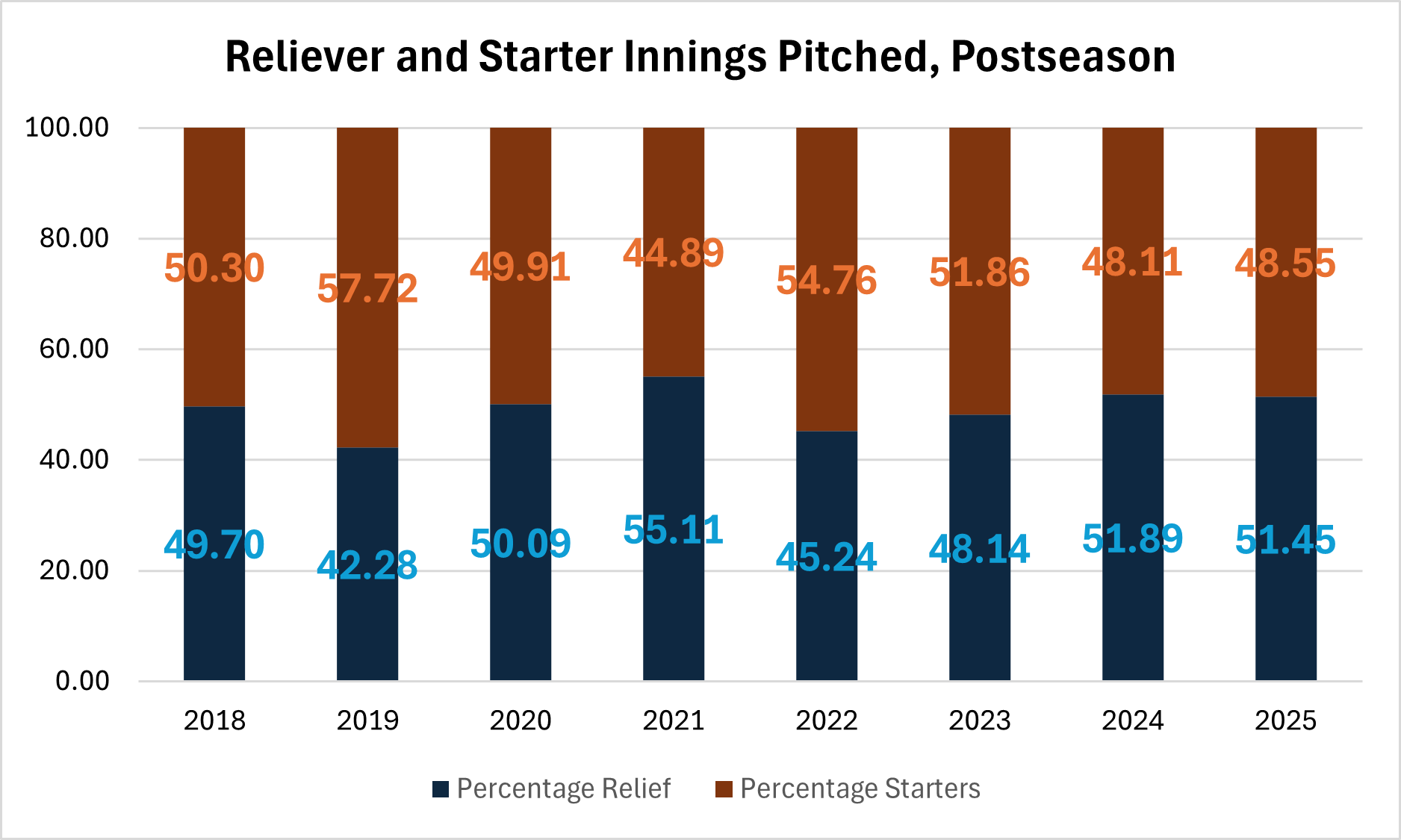

For years it has certainly been the trend, but this year, not so much. For the first time since 2022, when the playoffs expanded from the Wild Card game to a series, and teams backed off relievers with those addition innings to cover in a postseason run, relievers are throwing a lower percentage of innings in October than they did the year before. It’s a narrow decline, and they still throw more than 50% of all innings so far, but it is the potential start of a downward trend. For our visual learners, here’s what that looks like:

Naturally, I needed to investigate. What could be causing teams to reverse course this year? Are teams wising up to the risks of overusing their relievers? Maybe starting pitchers are better rested thanks to their reduced workloads in the regular season? Is this just the best crop of starting pitchers in the playoffs recently?

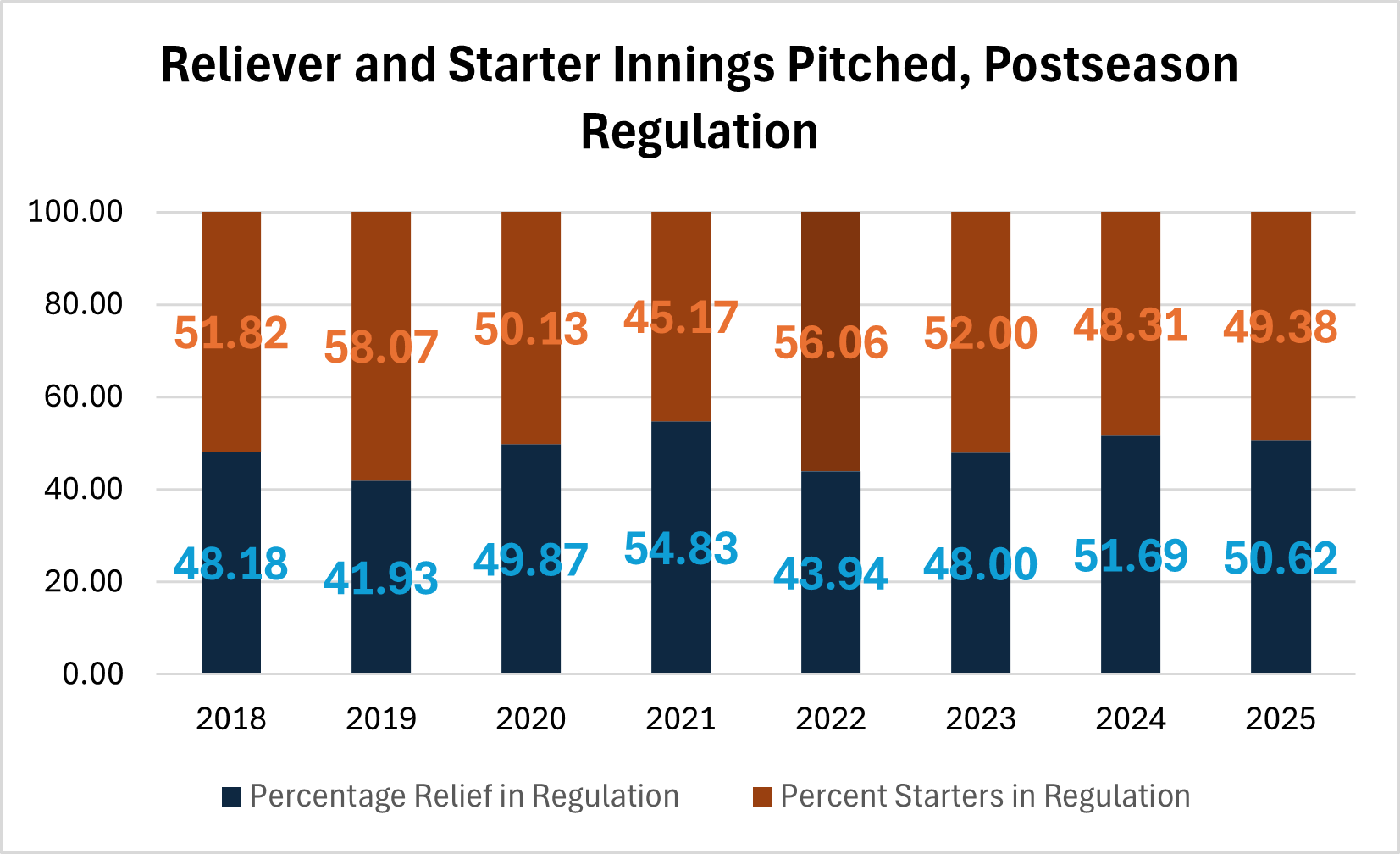

I started with none of those, funnily enough. My first thought was the data was being skewed by the uptick in extra innings affairs. Obviously, extra innings are typically thrown by relievers, and this year has seemed to have a lot of them. So I went through every postseason since 2018 – Nathan Eovaldi’s legacy game out of the bullpen seemed like something I wanted to include here – and removed extra innings from the equation to get a better understanding of the situation.

This confirmed my suspicions, at least. There’s been a disproportionate number of extra innings thrown this year, which is artificially inflating how many innings relievers are pitching. We’re only in the beginnings of the championship series and are only 8 extra-innings away from 2018’s peak of 18! Relievers couldn’t throw innings didn’t exist in 2020, which saw only 4 extra innings the entire postseason despite having the most games of any postseason ever, for one example.

The other thing I strongly suspect is influencing the count, but that I can’t check nearly as easily, is openers. This trend, which sees a reliever start the game and a starter relieve him for favorable matchups, got started in 2018 with the Tampa Bay Rays, and most small-market teams have used it since. That can skew the data by putting starting pitchers into what is technically still a “relief” role.

Consider Game 1 of the NLCS, when the Milwaukee Brewers opened with Aaron Ashby for an inning before Quinn Priester threw four against the LA Dodgers; those four innings count as a relief appearance from the arm with the second most innings on Milwaukee’s roster. Really? Unfortunately, without going through each playoff game’s box score since 2018 and arbitrarily deciding if the starter was actually a starting pitcher (ignoring the traps of piggyback starters or all-hands-on-deck elimination games), verifying this trend’s impact would be nearly impossible. Just know it’s extremely likely that the players we think of as “starting pitchers” are throwing more than the numbers suggest on the surface.

As for relievers pitching more and more innings in October, that trend is finally starting to peter out, which I, for one, am glad for. Dominant starting pitching from the best in the sport is exciting and I strongly prefer that to the endless bullpen carousel starting in the 4th or 5th inning. Certainly that strategy will always have it’s place, as few teams are really strong 1-5 in their rotation, and they don’t want to expose their backend starters. A.J. Hinch was careful not to push Jack Flaherty and Casey Mize too far, as one example. But if you have the horses, it makes sense to let your best arms handle as much as possible.

I’m not sure exactly why this reversal of trend is happening, though, unless it’s just the Dodgers riding four of the best starters in the sport hard because their bullpen isn’t nearly as good. Yoshinobu Yamamoto’s complete game one hitter for the Dodgers in Game 2 of the NLCS is the prime example to date, but Blake Snell threw eight shutout innings of one-hit ball in Game 1 as well. A new trend toward more work from starting pitchers will have to play out over years to really change the narrative that bullpens dominate in the postseason.

I don’t think we’ll ever return to the days of starting pitchers throwing 70% or more of playoff innings without some changes to the rules governing pitcher usage, unless the Dodgers throw 5 more complete games to win the World Series. Even that would be an outlier, not the trend. But things aren’t nearly as dire as the stats make them seem right now, either, which is a step in the right direction for baseball as a spectator sport. Baseball is better when the best pitchers in the game are more involved and going deeper into the biggest, most watched games of the season.