MLBbro.com, founded by veteran journalist and NABJ HOF Rob Parker, regularly spotlights Black and brown pro baseball players. The MSR does its best to keep pace with a similar emphasis on U.S.-born Black players at Minnesota Twins home games.

The Twins this season had four Black players — position players Byron Buxton and Royce Lewis, and pitchers Simeon Woods Richardson and Taj Bradley. All four saw time on our pages during the season.

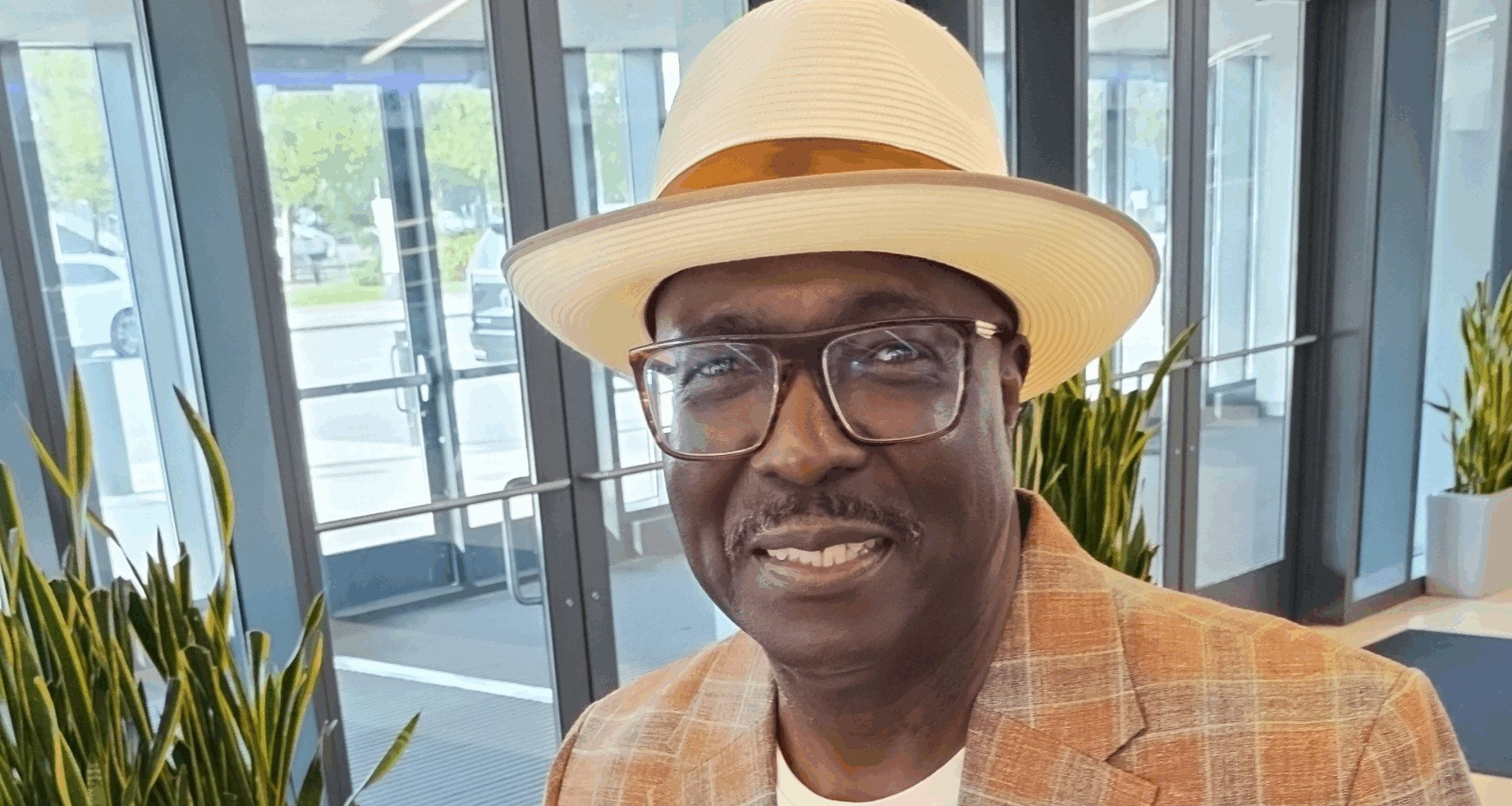

The MSR ran into Bob Kendrick, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum’s main man, before he spoke to a room full of Black sportswriters at this year’s NABJ in Cleveland. Kendrick lives and breathes Black baseball and the Negro Leagues, the precursor before MLB’s integration in the mid-20th Century.

We asked him if the major leagues will ever return to the levels in the 1990s when Black players made up almost 20% — it’s barely six% these days. Will Black fans return to America’s pastime as they once populated the ballparks around the country to watch the Black stars. You rarely see a Black face at Twins games for a myriad of reasons.

“I think these two things are synonymous,” stressed Kendrick. “The more Black players we get into the game, I think the likelihood of seeing that [Black] fan base [increase]. Representation really does matter.”

“We sure are moving the wrong way,” Kendrick continued. “I’m going to say that again: No one played this game better than we did.” Later, he spoke and took questions on the past and present state of baseball.

“Our game went from being what I would call a blue collar sport once upon a time to being a country club, pay to play kind of sport, and got extremely expensive,” bemoaned Kendrick. “I know people who are paying the equivalent of a college tuition for their child to play summer baseball, those travel teams, those league fees, and now [baseball] is an element of specialization.”

He easily reflected on the Negro Leagues, which was more than just baseball for many U.S. cities for many years. It was essentially an economic lifeline for the Black community in the decades of segregation.

“The more Black players we get into the game, I think the likelihood of seeing that Black fan base increase.”

“When we lost the Negro Leagues” starting in the mid-to-late 1950s, continued Kendrick, “we lost the catalyst that sparked economic development in so many urban communities. It brought a level of excitement that drew not only Black fans, but also a large contingent of white fans who went to Negro Leagues games because they were seeing something that they just were not accustomed to seeing, and it was a better brand of baseball.”

Black teams stayed at Black-owned and -operated hotels. The players and coaches ate at Black-owned eateries. Black fans did too, and patronized other Black businesses in the area as well.

“These businesses perished,” said Kendrick.

Fast forward to today, Kendrick told us he remains optimistic about baseball today when it comes to Black involvement. “What we’re starting to see now is more Black kids playing the game,” he said.

“Organizations like The Players Alliance are having a tremendous impact. So we’re getting more Black kids playing the game.

“We’re got to get them seen,” concluded Kendrick on Blacks playing baseball, beginning at the youth level and proceeding up through prep, minor and major leagues, “and then get them signed and into minor league organizations.

“And as we see the minor leagues continue to populate, I think we’ll be able to predict when the pendulum may shift the other way, and then hopefully the interest in African Americans in [watching the game], and the game will grow right alongside it.”

Charles Hallman welcomes reader comments to challman@spokesman-recorder.com.

Your Might Also Like