The Milwaukee Brewers are putting up some historically bad offensive numbers in this year’s NLCS. And while the Los Angeles Dodgers’ pitchers deserve some of the credit, it appears many of the Brewers have lost all semblance of their identity. Is it just a terribly timed cold streak, or is there a mental component to what is happening?

Hitting big home runs feels good, and everyone says you need them to win in the playoffs, so who knows if that success tweaked some things. My eye-test analysis for the past several games focused on the swing paths and body direction of multiple hitters. It was mostly clear against Blake Snell in Game 1 when I leaned in on Jackson Chourio and William Contreras’ at-bats. Both were pulling off the ball against Snell despite constant soft and away deliveries. It appeared they were gripping and ripping to knock the ball out.

Chourio seemed to correct himself quickly with a deep sacrifice fly in the ninth inning of Game 1 and his leadoff home run in Game 2, each to right-center field. Unfortunately, the apparent pull-happy swings haven’t only been present with those two, and upon reviewing some Statcast numbers, there might be some evidence to support my thoughts.

The beginning of the end for the Brewers’ typically hitting styles might stem from their Game 2 win in the NLDS when they used three home runs (two of them three-run homers) to beat the Chicago Cubs 7-3. From that point through Game 3 of the NLCS, the Brewers have a .140 batting average and have scored 1.5 runs per game. This is not to say that players are intentionally trying to do things differently (though some look like they are), but that hitting is extremely mental. Guys can fall into the trap of subconsciously adjusting their swings.

There are a few areas to look at with a player’s swing to get a sense of how they are swinging. First is attack direction, which measures the angle at which the bat’s sweet spot is traveling at the point of impact. It’s measured in degrees to the pull side or to the opposite field.

The other two metrics are the intercept points compared to the front of home plate and compared to the batter’s center mass. Typically, hitting the ball slightly in front of the plate is ideal for hard contact and quality launch angles, due to the barrel position and the force exerted on the ball. But, too far out front leads to weaker contact. As far as where the intercept point is compared to a hitter’s body, the further out in front you get, the more likely it is that the hitter’s hands are extending too soon away from his body, an indication he is swinging “around the ball,” which often leads to easy grounders or top-spin flies.

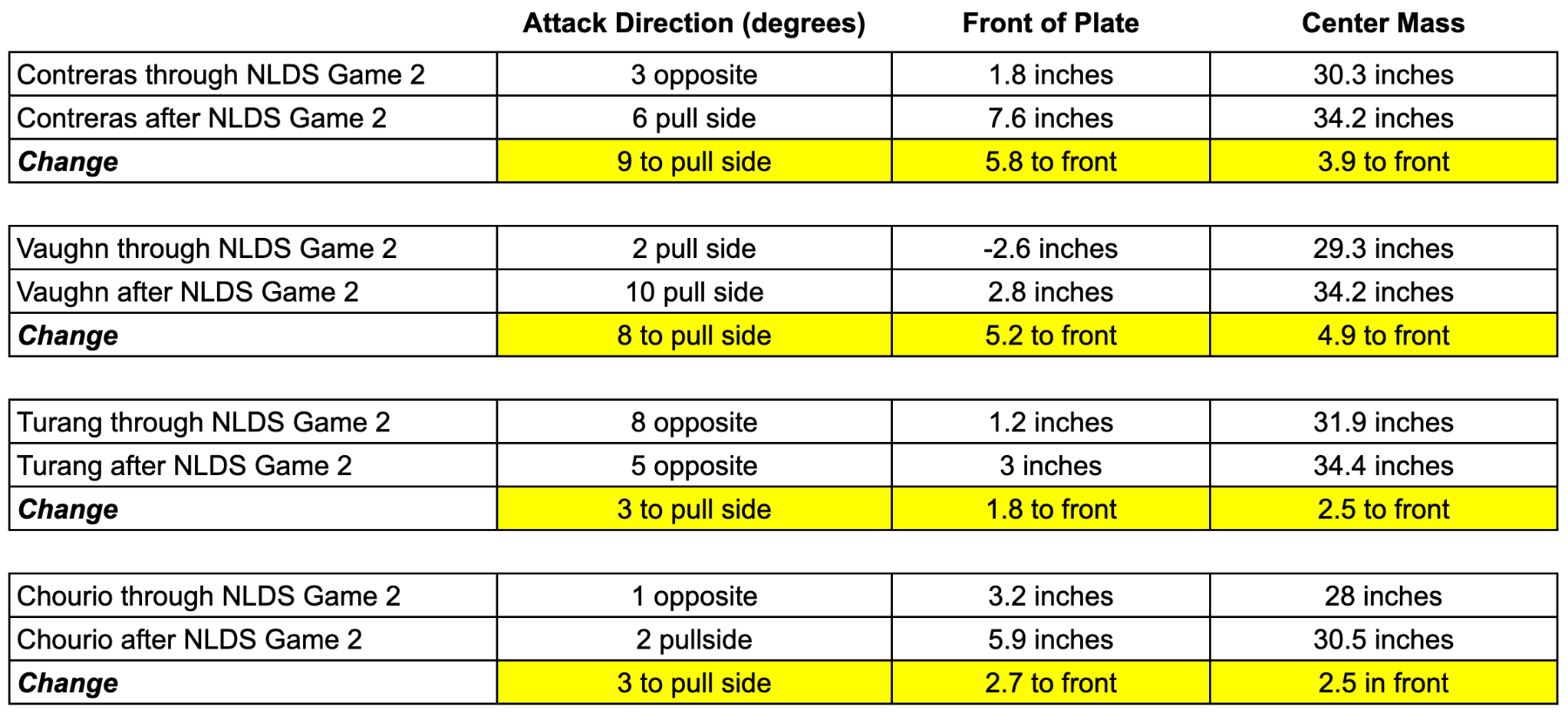

With that in mind, here are some of the figures comparing the numbers from Opening Day through NLDS Game 2 and then what they look like since then:

Contreras and Andrew Vaughn have seen their swing directions move extremely to the pull side. You also notice significant moves forward in their intercept points, both in front of the plate and in front of their bodies. All indications of looking to yank balls with shoulders and hips opening up, and their hands extending early and away from their bodies, often leading to the top hand rolling over. They have had plenty of pulled groundouts lately, and while some were hit harder, it’s been an overall struggle.

It’s interesting to note that all season, Contreras’ average attack direction was three degrees toward the opposite field—consistent with his strength of driving the ball that way while still handling inside pitches. Since that NLDS Game 2 homer he crushed down the left field line, he’s trying to pull everything. For Vaughn, the most intriguing part is that he typically made his contact about two-and-a-half inches behind the front of the plate, staying behind the ball longer. Since his huge three-run home run in that same Game 2, he’s leaned out to nearly three inches in front of the plate. Those are sizable changes for each.

Turang and Chourio haven’t been quite as extreme, and in fairness, Chourio clearly made adjustments and has fallen into some bad luck, especially in Game 3 of the NLCS. Turang has been downright brutal, though it looked like in the last game he was making an effort to sit back on the baseball better. For both of them, however, their swing issues have led to more strikeouts. In the last six games, the pair has combined for 16 strikeouts and just two walks.

Chourio, Contreras, and Vaughn were the ones to homer in the NLDS Game 2 that might have sparked some issues. Of course, Contreras, Vaughn and Turang then homered in Game 5 of that series, too. It’s just difficult to see these metrics and not believe some of the power swings, which were enormous in helping beat the Cubs, haven’t gotten into guys’ heads. Hitting is hard, and they are human.

For those wondering about Christian Yelich and Sal Frelick, they have their own issues to work through. Each of their intercept points versus the front of the plate has moved forward, while those points compared to their center mass have moved backward. This would indicate they are either pulling their shoulders or leaking their hands forward early while the barrel drags behind. Those movements seem more geared toward trying to cheat ahead on pitches or the opposite, major indecisions where the body is turned but the actual swing decision is last-second. Either way, more of a timing or pitch recognition problem, perhaps.

No matter how you slice it, the Brewers offense as we knew it in 2025 has disappeared – or more accurately – changed over the last half dozen games. Barring a miraculous and historic comeback in the NLCS, it will be a shame that the third-best scoring offense in baseball will have wasted the Brewers’ mostly terrific pitching against the powerful defending champion Dodgers.