Generally speaking, we don’t celebrate the 1925 Yankees, and understandably so. The team finished in seventh place in the American League with a 69-85-2 record. Amidst a stretch where the team won multiple World Series titles that established the first true Yankees dynasty, the 1925 squad limped through the season; in truth, the only moment worth celebrating from that team would be the beginning of Lou Gehrig’s Iron Man streak on June 1st. Babe Ruth’s infamous “Bellyache Heard ‘Round the World” was the main story of this lost year, which remarkably was the Yanks’ lone losing season between 1919 and 1964.

So why exactly are we diving into the archives to look at this squad today? Because, much like the game that the Yankees would win on the road in Cleveland 25 years ago (featured today in our 2000 Yankees Diary), the 1925 club found themselves mired in a crazy game a century ago — although unfortunately for them, they would come out on the losing side.

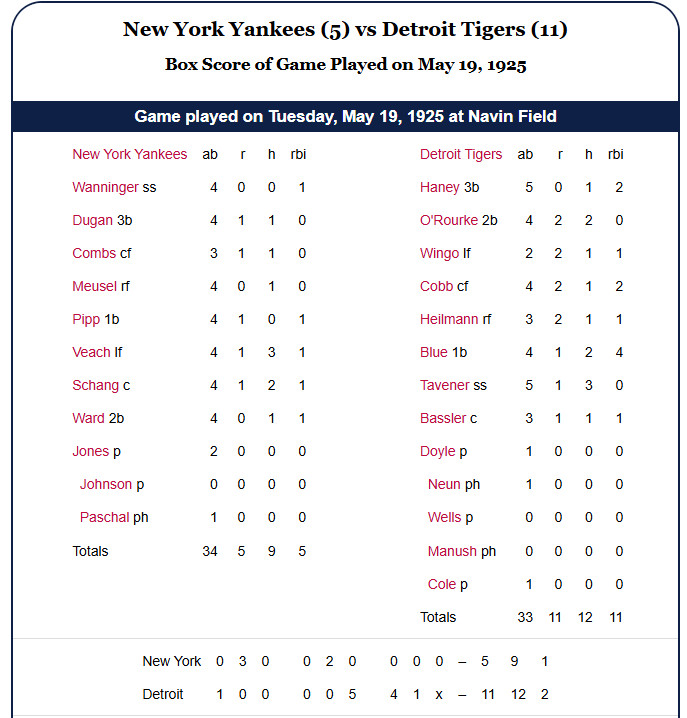

Box Score courtesy of Baseball Almanac.

Sad Sam Jones would get the ball for the Yankees, the pitcher best known for throwing the other Yankees no-hitter on September 4th. The Detroit Tigers punched first, with Frank O’Rourke tripling with one away and Al Wingo bringing him home on a sacrifice fly. That would be all the Tigers would get though, at least in the early going.

Meanwhile, the Yankees offense—sans Bambino, due to the aforementioned “bellyache”—jumped on Detroit Tigers starter Jess Doyle in the top of the second. The soon-to-be displaced first baseman Wally Pipp led off the frame by reaching on an error. Bobby Veach, Wally Schang, and Aaron Ward followed that up with singles that plated two runs, and starting pitcher Sad Sam Jones worked a walk to load the bases. Paul “Pee-Wee” Wanninger brought in Schang on a sacrifice fly to left, giving the Yankees an early 3-1 lead.

They would add to this lead with another rally in the top of the fifth. Jumpin’ Joe Dugan reached on a bunt single to lead off the inning. Hall of Fame center fielder Earle Combs followed that up with a walk, and a Bob Meusel sacrifice bunt attempt loaded the bases. While Pipp grounded into a double play, Dugan scored and Combs went to third; Bobby Veach then brought him home with a single to right field, giving the Yankees a 5-1 lead.

All of these details, however, were relegated to the bottom of the New York Times article about the game; all that mattered to reporter James R. Harrison was Jones’ meltdown in the sixth and seventh, when “Sad Samuel began exuding passes and perspiration.”

Frank O’Rourke led off the bottom of the sixth with a walk; Wingo followed with one of his own. Player/manager Ty Cobb then plated them both with a triple “into the temporary seats in right” — no, I’m not exactly certain what that means, but I’m assuming it has to do with the numerous renovations and expansion Navin Field (later Tiger Stadium) would undergo throughout its history. Cobb would himself score to bring the Tigers within one on a Harry Heilmann single.

After getting a pair of groundouts, which would advance Heilmann to third, Jones intentionally walked Johnny Bassler to bring Tigers pitcher Ed Wells to the plate. Cobb countered by sending up Heinie Manush as a pinch-hitter, who worked a walk. Fred Haney followed that up with a two-run single that gave the Tigers a 6-5 lead.

As Harrison put it, “The seventh was also sad” (see, it’s not just modern bloggers who like puns!). With one out, Jones lost the strike zone completely, throwing 11 consecutive balls to walk Cobb and Heilmann and give Lu Blue a 3-0 count. At long last, Jones threw something over the plate…which Blue laced into center field. Not only was Combs unable to come up with it, he couldn’t keep it in front of him, and Blue came all the way around to score on an inside-the-park home run.

The next batter, Jackie Tavener, attempted to bunt for a hit. He would find himself on third base, as Schang, the catcher, didn’t throw the ball to Pipp at first base, but to the fans in the right-field bleachers. Johnny Bassler then laced a single to left, scoring Tavener. While Jones was able to get out of the inning without further damage, his day ended there, with Hank Johnson coming on in relief in the eighth (who, himself, would walk two batters and tack on another run).

At the time, this game was considered a bit of an outlier: after all, it’s not exactly common for a pitcher to be dealing for five innings, only to completely lose the strike zone, walk six batters in two innings, and allow nine runs in two innings. By modern standards, it is borderline lunacy — any manager who wouldn’t pull their pitcher after Heilmann’s single in the sixth at the latest would be subject to brutal questioning from the media, and if the game was important enough, might find a pink slip on their desk in the morning. That didn’t happen here, though; Harrison’s article does not question the decision-making of manager Miller Huggins in the slightest, and he would continue to helm the Yankees until his sudden passing in 1929.

Ultimately, a look back into the archives like this is a nice reminder of just how much the game of baseball has changed over the last century.