When a player with a long track record of average or worse production suddenly enjoys a half-season of excellence, it’s natural to expect some regression. Baseball is a game of adjustments, and every time a player gets ahead of the curve for a bit, the league adjusts to them, forcing them to make changes in reply. That’s what makes it so hard to sustain success, even for exceptionally talented players. For those who start from a lower baseline and have to make relatively major tweaks to get to a new level of performance, there’s often a greater vulnerability to the adjustments the league makes; a big shift in process leaves one a bit off-balance (metaphorically) and prone to exploitation when opponents force the next shift.

Of course, a really good process is still valuable, and if you want to evaluate the staying power of a sudden performance change, you have to understand the changes that brought it about. Did the player get lucky for a while, or did they make concrete adjustments that let them tap into their talent more fully? Just as importantly, since having made real changes doesn’t guarantee that a change in performance has staying power, how sustainable is their new process, if they have one?

In the case of Brewers first baseman Andrew Vaughn, there are lots of good indicators. By way of quick review (one most of us won’t need, already being familiar with the team and the season of which Vaughn was such a big part), Vaughn batted .246/.297/.402 last season with the White Sox, and was hitting .189/.218/.314 for them when he was demoted to the minor leagues early this year. Milwaukee traded Aaron Civale for him, and called him up in early July after Rhys Hoskins got hurt. For the Crew, he batted .308/.375/.493 in 254 plate appearances during the regular season, and although he was just 4-for-26 in the playoffs, two of those hits were huge home runs. His strikeout (13.7%) and walk (9.9%) rates after joining the Brewers easily bested anything he managed during his White Sox tenure, and he tapped into more power after the trade, too.

Immediately, Vaughn’s adjustments in his new organization were clear. He began chasing less outside the strike zone (dwon from 36.1% of the time to 24.6%, according to Statcast); that grabbed the headlines. By not expanding his zone as much, he was able to draw more walks, but also get into better counts and attack pitches more effectively.

There were also key changes, though, in what his stroke looked like when he did swing. I chronicled some of them back in late August. Vaughn’s upper and lower halves worked in sync better after the trade, and he adopted a more aggressive leg kick. He also got his hands moving a bit sooner.

Now, though, I’d like to delve a little more into the rest of his swing. Vaughn incrementally (though only incrementally) increased his swing speed after the trade, but interestingly, he also reduced the length of his swing pretty substantially. The tip of his bat traveled farther from the start of his swing to the contact point when he was with Chicago than after he joined the Brewers. That’s not usually how things work.

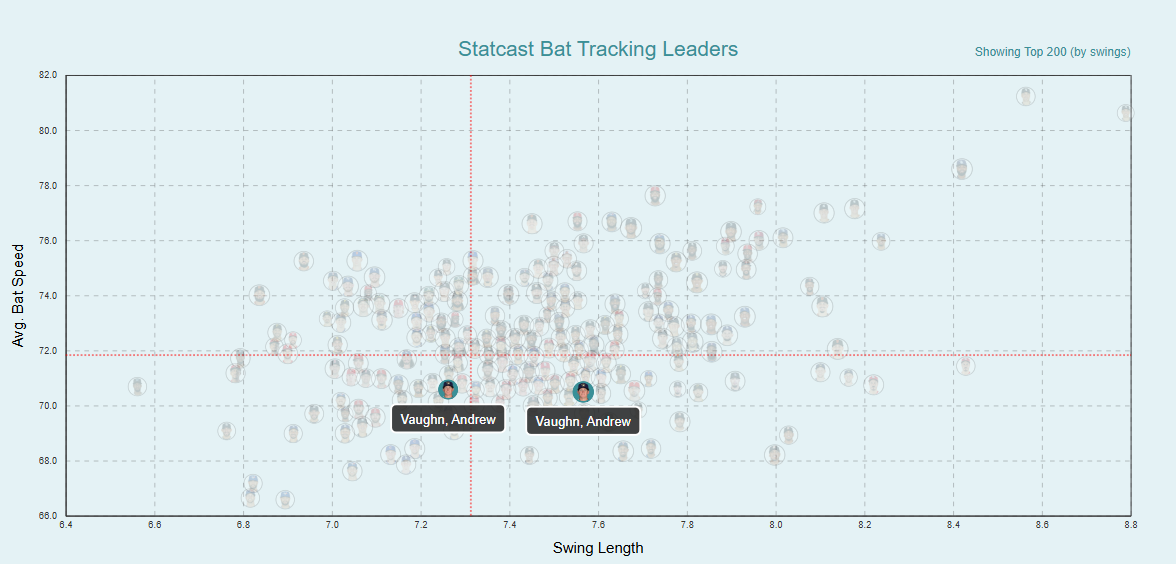

This is a chart showing swing length and bat speed for right-handed batters in 2024 and 2025, broken down by season. I’ve highlighted Vaughn, whose swing shows up as much shorter, but essentially the same speed this year. Usually, swinging harder means extending your arms more and swinging bigger. Naturally, that leads to more whiffs, but it also allows you to access more power. As you can see, the mass of data points rises from left to right, albeit imperfectly: the longer your swing, the faster, and vice-versa.

The chart doesn’t even tell the story, in full. Vaughn’s 2025 data for that visual still has his time with the White Sox baked in; he swung a tick faster and his swing was a hair shorter after the change of scenery. This is an extreme change: more swing speed from, in a sense, less swing.

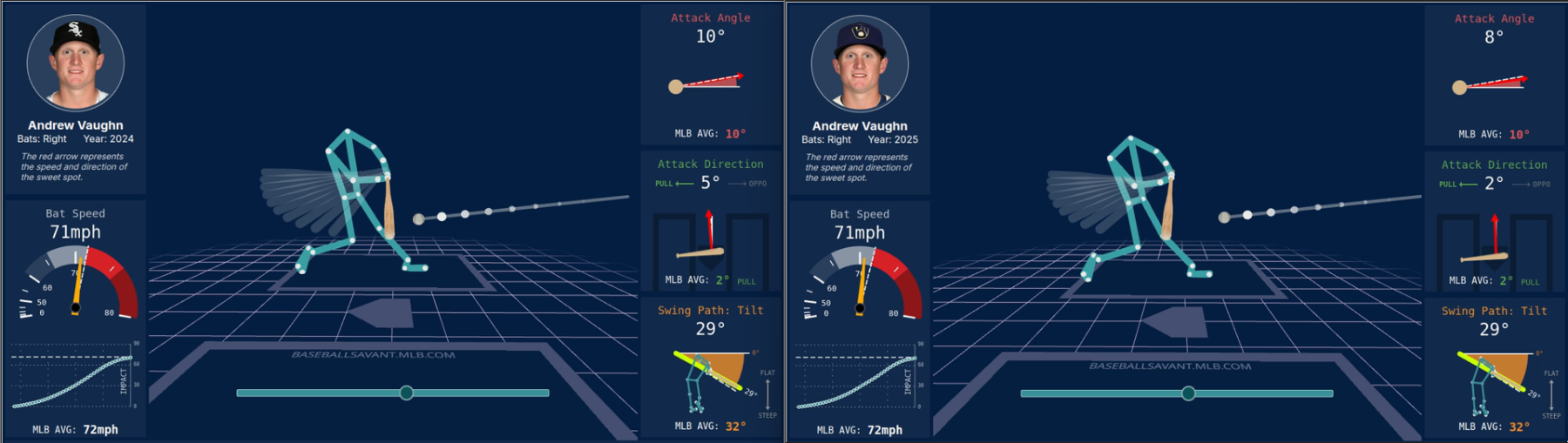

How did that happen? In short (no pun intended), he got better at targeting the pitches on which his swing is compact, but still powerful. Here’s his swing, at a glance, for both 2024 and 2025. This is the frame just before his bat meets the baseball; notice the way he’s carrying his hands higher and closer to his body this season than last.

If you’re going to hit the outside pitch or the low pitch, your swing is going to get a little long. You have to go from up high to down low, or from where you’re standing out to the other side of the plate. Often, those balls down in the zone are breaking or offspeed pitches, which the batter catches farther out in front of themselves, which shows up as greater swing length. That’s fine; not all swing length is bad. But it does mean your swing is longer.

Vaughn did two different things, after coming to the Brewers, that led to his swing length being so much shorter: adjust the way he swings, and adjust the pitches (even within the zone) at which he swings. To wit, here are his swing lengths (top) and swing rates (bottom) by pitch location, with the White Sox (left) and with the Brewers (right).

.png.30a9b8f25aef83e754737eedfc9a1238.png)

It matters, to be sure, that Vaughn clearly started attacking pitches at and above the belt and on the inner half, while letting low and outside offerings go. However, as you can see, his swing is also shorter, regardless of pitch location. To visualize that (and understand how significant a change it is), let’s look at how he addressed the ball on similar pitches, before and after being traded.

.png.fea3526f7a0258e874d0171ab19eadf5.png)

On top, we have two images of Vaughn going after slow pitches from left-handed pitchers, each of which ended up basically in the middle of the strike zone. On the bottom, we have firm sinkers from righty hurlers, around waist-high but boring in on him. All of them are clipped at the same point in the rotation of his hands—the same moment within his swing.

To accentuate the crucial difference, I’ve added arcs that show the relationship between his right hip, armpit and elbow in each swing. It’s easy to see what’s going on. After his sojourn in the minors and being recalled by his new team, Vaughn kept his hands in much closer to his body. This shared instant of the swing is a telling one, because of what’s happening with his front shoulder. Instead of letting his hands take his bat on a wide arc through the hitting zone, Vaughn is rotating that front shoulder out and backward, pulling the bat through closer to his body and creating that extra bat speed he found with the Crew. It’s a more compact, cleaner attack. It’s a shorter and a faster swing, and (relatedly, but not only on that basis) it’s a better swing.

Vaughn’s batted-ball data didn’t look all that different after he joined the Brewers than it did before. By better organizing his strike zone, though, he was able to be more selectively aggressive. His swing was more repeatable and less manipulable, for pitchers trying to poke holes in his approach.

These changes all have to survive an offseason, now, and then they’ll have to survive the new ways that teams pick on him and his new profile in 2026. He had to do a lot to come this far, and that means he might slide backward next year. If he does, though, it’s not likely to be a radical regression. Don’t expect Vaughn to hit over .300 again, but the modicum of power and patience (and the improved contact rate) all look real. A collapse back to what he looked like early in 2025 is out of the question. Even production as sluggish as his 2024 numbers would be an unexpected disappointment. If Vaughn maintains the work ethic and discipline he showed when the organization first brought him aboard, he should be something like a .280/.350/.450 hitter next season. His adjustments are real, and while all adjustments beget counteradjustments, his are well-selected to survive that next challenging phase.