Editor’s Note: This story is part of Peak, The Athletic’s desk covering leadership, personal development and performance through the lens of sports. Follow Peak here.

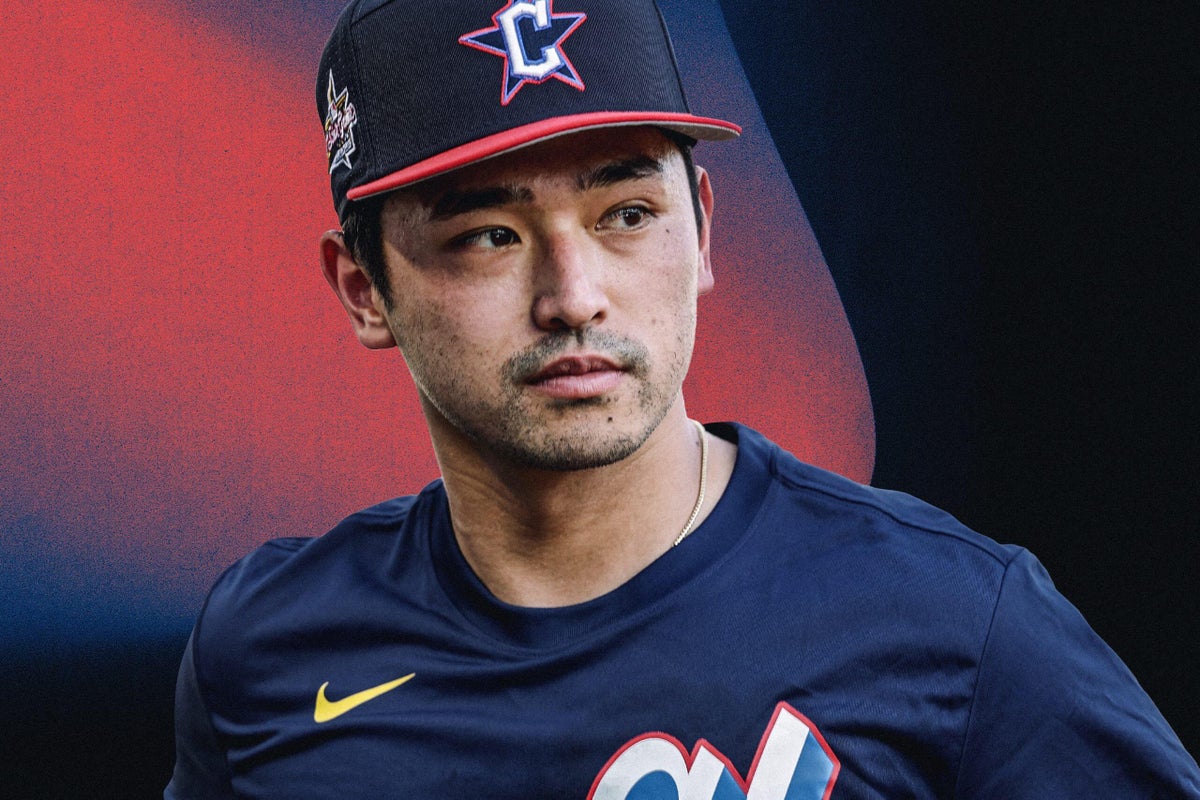

Steven Kwan is a two-time All-Star, a three-time Gold Glove winner and the leadoff hitter for the Cleveland Guardians.

CLEVELAND — I get nervous. Every game. People who say they don’t get nervous are either lying, or they’re José Ramírez. I don’t know if José ever gets nervous.

The national anthem is my last chance to center myself before first pitch. It’s a constant, a chance to maintain a routine. It’s something I can depend on and something I can control in a game in which there’s so much we cannot. So as I stand on the baseline, I start counting.

Breathe in. One.

Breathe out. Two.

As I make my way to 10, it’s funny how many thoughts can flood your mind: What am I gonna do in my first at-bat? What’s the third-base umpire’s name? Do I have time to go to the bathroom?

When you’re in the heat of the battle, staring down a pitcher who knows your weaknesses, your tendencies and your plan of attack, you’re probably going to have hundreds of things cross your mind. Those thoughts can take over. But they’re just thoughts, and if you can identify that in the moment, the thoughts don’t seem so terrifying or real.

That breathing exercise during the anthem basically simulates what I’m going to experience at the plate when I lead off a game a few minutes later.

As much as certain aspects of Major League Baseball have become desensitized now that I’m nearing the end of my fourth season, so much of it still seems surreal and, at times, overwhelming.

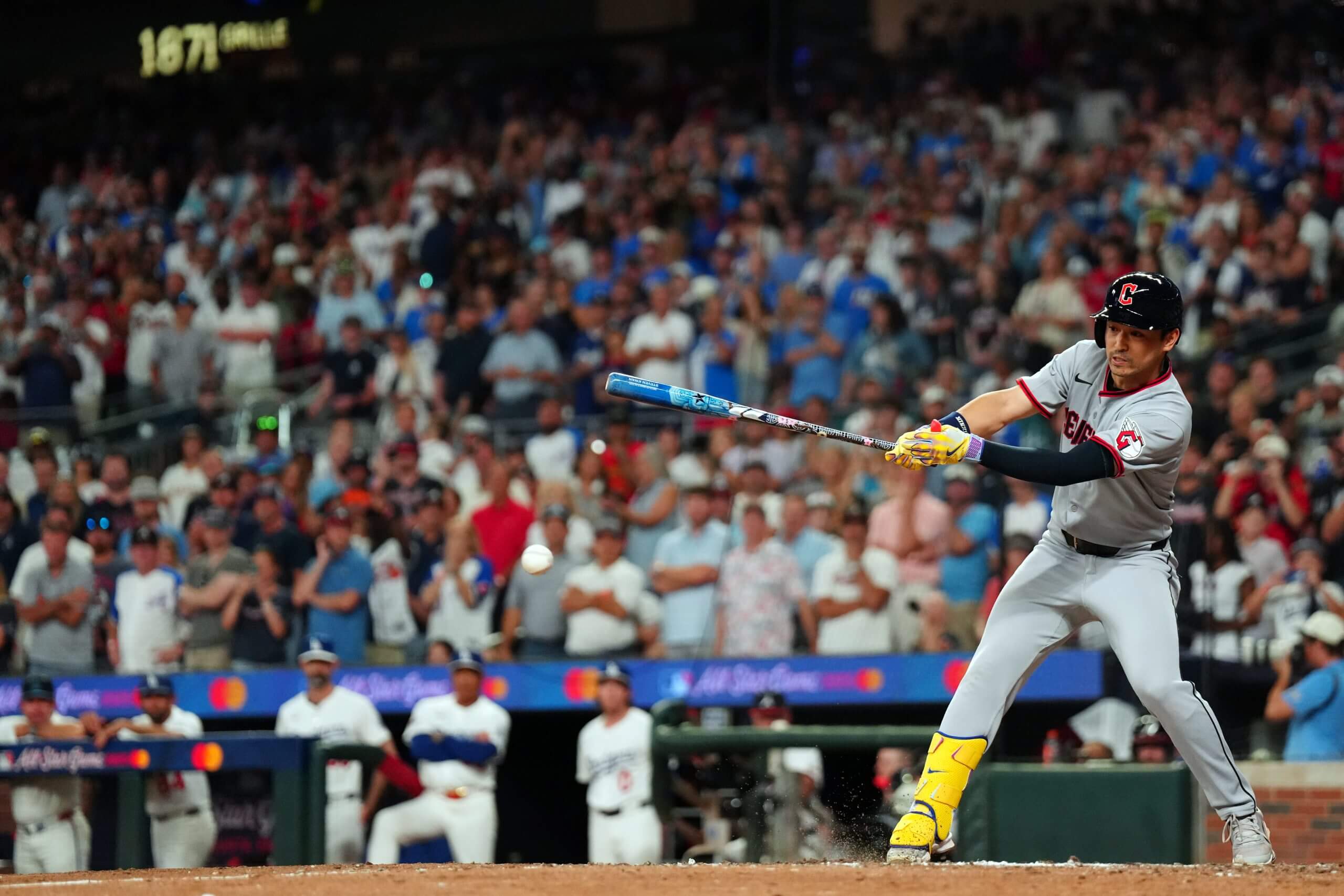

Look no further than an at-bat I had on July 15 at the All-Star Game.

I had been dealing with a sore wrist since late May, when it sort of folded underneath my arm on an awkward slide into second base. I spoke with Aaron Boone, the manager of the American League team, and Stephen Vogt, my manager in Cleveland and a member of Boone’s American League coaching staff, about what I was feeling. The plan was for me to get one at-bat.

We were trailing 6-0, and it seemed like it would all go according to plan. I’d get my one at-bat, head back to Cleveland and start preparing for the second half.

The next thing I know, I’m stepping up to the plate with two outs in the ninth inning, the AL down by one and the tying run at third base.

My heart was beating out of my chest.

Steven Kwan felt familiar nerves when he came up to bat in a key moment this year at the MLB All-Star game. (Mary DeCicco / MLB Photos via Getty Images)

It felt like my major-league debut in Kansas City in April 2022. That was a whirlwind. The lockout delayed spring training that year, and even though I had been invited to Guardians big-league camp, in my mind, I was going to be in the minors until at least August. At no point did I think I would make the Opening Day roster, and I certainly never imagined myself in Terry Francona’s starting lineup on a snowy afternoon at Kauffman Stadium. Francona initially made it seem like I was being cut when he called me to his office to deliver the news at the end of camp. That was a roller coaster of emotions.

The night before my debut, I had dinner with my parents and then had no trouble falling asleep. But I woke up in the middle of the night with a coughing fit, and that’s when the gravity of everything hit me. That’s when I try to catch those big thoughts and not give them any more power.

I don’t even remember much about my first at-bat. Salvador Pérez was catching and Zack Greinke was pitching, which is just crazy. That’s two Hall of Famers right there. I just remember the outcome (a groundout to short), which probably speaks to how sped up I was.

That’s how I felt as I strolled to the plate with a chance to tie the All-Star Game this July. I couldn’t calm down my heart, but in a good way. Those are the moments we live for. Those are the moments that seem unrealistic when you’re an overmatched freshman at Oregon State who doesn’t think he belongs on the same field as future big leaguers Adley Rutschman or Trevor Larnach. On a rare good day, I’d compare my results to whatever Nick Madrigal did, just to knock myself down a few pegs. Those guys, my teammates, were all bound for the big leagues and everybody knew it.

I wouldn’t allow myself to believe the same about me.

To a degree, that mindset hasn’t completely disappeared. I looked around the field at the All-Star Game and wondered if I belonged. Julio Rodriguez made the All-Star team and he faced some backlash because of his numbers. Well, my numbers weren’t too different from his. I could have been Cal Raleigh and I would have found something to doubt. It just never goes away. That’s just who I am in my head, a self-saboteur and a deprecator. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t think my first All-Star Game last year would also be my only All-Star Game appearance.

There’s a level of that impostor syndrome that’s key to my success — never letting myself get complacent, never letting myself think I belong. It’s probably not healthy, but I think it helps in the grand scheme. It motivates me to keep up with my routines — the meditating, the breathing exercises, the journaling, the reading. All the stuff that becomes more and more difficult to stay disciplined with the deeper you get into the 162-game grind.

My wife, Sam, has been a huge help, too.

The thing I love most about her is she really doesn’t care about baseball. I’ll be upset about going 0-for-5 or that we lost and she’ll lighten the mood and provide some perspective. She just got her Master’s in nursing. She’s saving lives. She’ll make in a year what we make in a week. That’s ridiculous. That’s not how it should be. But having her continually pointing me north and keeping me grounded, that’s been the most important thing. You see a lot of people spiral really fast if you don’t have somebody keeping you accountable.

It’s funny, I got the All-Star nod this year, so you look on paper and you might think, “Oh, he had another career year.” But that’s not how it is at all. My hitting is far from where I wanted it. I was dealing with that wrist injury, but there’s no context there when you just look at the numbers. And in a lot of ways, we are defined by our numbers, so it’s a constant struggle. The only solution is to play better. It’s why this game saps so much from everybody.

This is a terrible way to think, but I never want to be a rookie’s first strikeout. I never want to be the last out of the game.

So when I was at the plate with the All-Star Game on the line, with two outs and two strikes, I’m like, “I am not gonna let there be a highlight reel on ESPN of me striking out.” That stress and anxiety locked me in. In a weird way, it freed me and gave me confidence to keep battling in the at-bat. It was a good kind of stress, a reminder that it’s OK to be nervous, whether you’re a 5-foot-8 dude from Fremont, Calif., with a collage of Sports Illustrated cutouts still hanging on the bedroom wall of his childhood home, or you’re Aaron Judge.

That’s what the breathing exercises are for.

The pitcher, Edwin Díaz, called a timeout in a 1-2 count, and I remember briefly smiling and being able to take inventory of what was happening, though looking back, it was kind of torturous. The moment felt so familiar, like a playoff game in Cleveland. The nerves from not wanting to let down Cleveland and my team prepared me for that moment.

And I tied the game with a 53.9-mph infield grounder, just as I planned.

— As told to Zack Meisel

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Kevin C. Cox / Getty Images)