In ways familiar and excruciatingly new, Zebby Matthews keeps underachieving. He throws 96 miles per hour, and can reach 99 semi-regularly. He has six pitches, including a couple of bat-missing breaking balls. He fills up the strike zone. He even has a great, folksy baseball name—the kind of name baseball needs a really good player or two to have, in every generation. Alas: he’s not that really good player, so far. In 25 starts and 117 innings over parts of the last two seasons, Matthews has a 5.92 ERA.

In theory, he should be much better than that. The stuff is certainly better, and so are his peripheral numbers. Matthews has fanned 24.7% of the batters he’s faced in the majors, and walked just 6.6%. He had a major home-run problem in his rookie stint last season, but brought that under control in 2025. Though his FIP is a still-underwhelming 4.41, all the building blocks of a pitcher with a sub-4.00 ERA are here. He just hasn’t been that guy—or anything close to it.

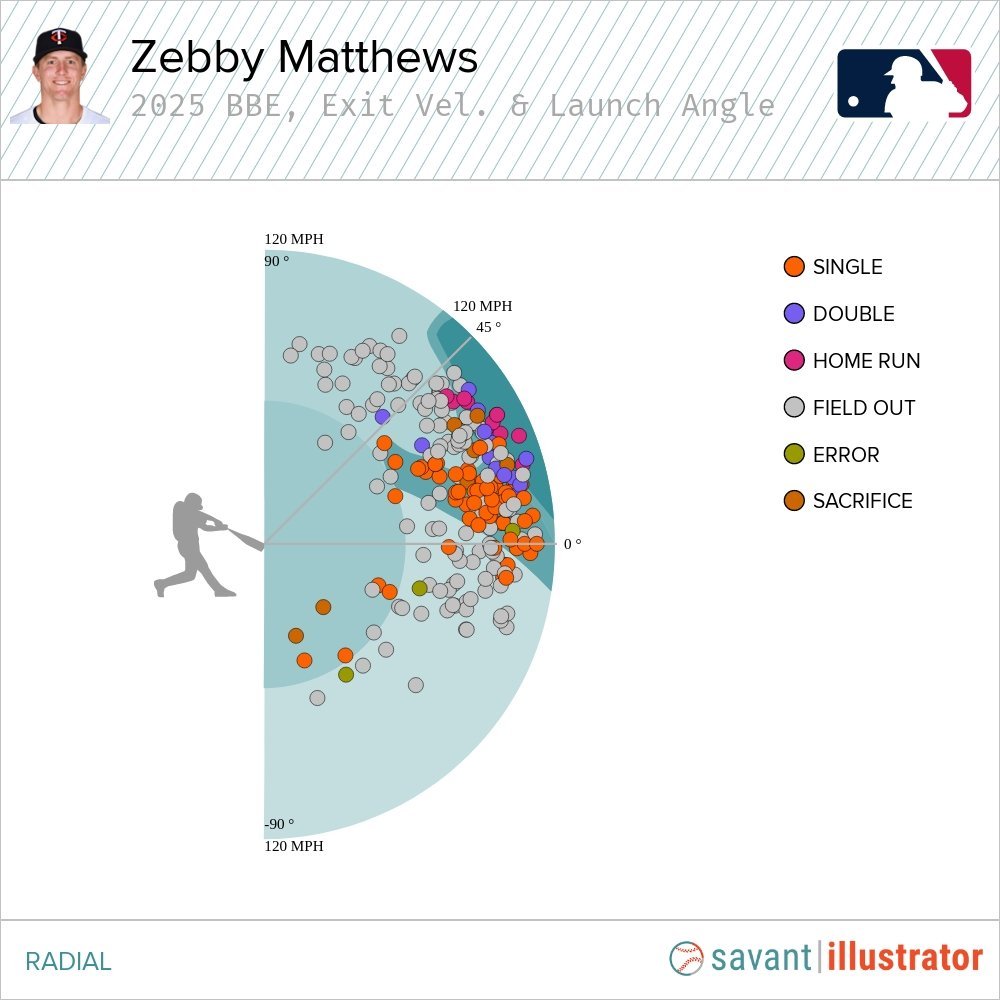

The problem—the reason why Matthews has been so unsuccessful—is simple: hitters just keep finding singles against him. He’s allowed a .361 batting average on balls in play so far in his career, which is too high to permit any pitcher to function well. Whenever a hurler is running that high a BABIP, the temptation is to declare them unlucky. In Matthews’s case, though, that’s only half-true, and the half of it that’s true is a more lasting and existential kind of bad luck, rather than the fluky kind that time and nature take care of.

First of all, Matthews gives up too many batted balls that have a very good chance to be hits. Of the 192 pitchers who allowed at least 200 batted balls in the majors this season, only two had a higher percentage of those batted balls fall into the bucket Statcast labels “Flares and Burners”. That category is made up, basically, of three kinds of hits, though they scatter along a spectrum (rather than neatly subdividing themselves):

Low line drives

Extremely hard ground balls

Softly-hit fly balls at launch angles too low to be pop-ups; the kind that fall between infielders and outfielders

On “Flares and Burners,” the global batting average is right around .660. Thus, the fact that Matthews gives up so many of those batted balls is a problem. Here’s the other problem: when Matthews allowed those batted balls, opponents batted .789. In that same sample of 192 hurlers, the only one who gave up a higher batting average on flares and burners was Austin Gomber.

We have to engage with both of these facts, but let’s start with the second one. That’s where a kind of bad luck is infecting Matthews—only, it’s not the bad luck of a ball just being hit to the wrong spot four or five times, where nothing could be done. Rather, it’s the bad luck of having pitched in front of the Twins’ defense. Unfortunately for Matthews, that group is unlikely to be stronger next year than it was in 2025.

For all pitchers, the Twins allowed a .699 batting average on flares and burners this season. Only the Angels were worse. Batted balls like those test a defense as much as any others, and the Twins failed that test more often than almost any other team. They simply don’t have the personnel to convert those plays into outs at even an average level.

Unless the team rededicates itself to defense this winter, the likely starters at third base, shortstop and second base will be Royce Lewis, Brooks Lee and Luke Keaschall, respectively. Those three are all average-minus defenders. There’s a slightly better chance that Minnesota will have above-average fielders in the outfield, but Byron Buxton is aging and might not be long for center. It won’t turn out any better if Matthews shows up in 2026 and continues giving up batted balls like these. They’re hits most of the time, and the poor defense behind Twins hurlers will exacerbate that.

Let’s talk, then, about the fact that Matthews gives up so many of those batted balls in the first place. Is that something he can fix? Or is it an intrinsic aspect of his game?

Alas, it’s closer to the latter. Unless Matthews makes some changes to the way he pitches, he’s likely to keep giving up a lot of those batted balls. He limits very hard-hit fly balls (the Barrels you’ve probably heard much more about, relative to the flares and burners) reasonably well, and his stuff profile can induce whiffs, but he’s not good at manipulating batters’ launch angles. That begets a lot of near-automatic singles.

Matthews fills up the zone, even though he’s walked more batters since reaching the big leagues than he did in the minors. Among the 260 pitchers who threw at least 1,000 pitches this year, he was in the 78th percentile for Called Strike Probability, according to Baseball Prospectus. That reflects not just the frequency with which a ball is technically in the zone, but the average likelihood of a pitch they throw being called a strike if not swung at. As such, his standing within the league means that Matthews is throwing pretty hittable stuff; he leaves a lot of white on either side of the ball. He doesn’t perfectly target the edges, laterally or at the top and bottom of the zone.

Location is an issue, then. Unfortunately, so is raw stuff. Only Matthews’s slider reliably avoids being hittable; hitters square him up a lot. A change of pitch mix (ratcheting up the frequency with which he throws his sinker to righties, for instance) could help, but it’s not obvious that he can either shape or locate that pitch (or any other, save his very good slider) well enough to prevent an abundance of this kind of hit.

Even if there’s no major roster overhaul, the Twins could use their very best defensive lineups behind Matthews in 2026 and achieve a modest improvement in outcomes. Even if Matthews can’t avoid giving up this kind of contact when hitters do touch him, he might be able to miss more bats by using strike-to-ball breaking or offspeed stuff more often, or by better elevating his fastball. There are plenty of ways he can take a big step forward next season, but doing so will require at least some mitigation of the tendency to give up lots and lots of singles by letting opponents hit lots and lots of balls with high expected batting averages—even if the high expected slugging average that plagues some similar hurlers isn’t among his problems.