MESA, Ariz. — Rarely has a Major League Baseball team’s jersey said as much, literally and figuratively, as the uniform the Athletics will wear in 2025.

On one shoulder will be a patch representing Sacramento, where the team begins a residence of at least three years starting March 31. After 57 years in Oakland — the last few drowned out by the should-I-stay-or-should-I-go-now antics of the team and the politicians it fought with over a new stadium — the A’s are temporarily moving into Sutter Health Park, a minor-league ballpark in West Sacramento never meant to host major-league games.

On the other shoulder will be a patch representing Las Vegas, where the A’s plan to open a new stadium for 2028. It’s normally unthinkable for a sports team to rep two cities at once, but the A’s remain in an unprecedented and at times surreal position, even as some of the recent chaos subsides heading into Sacramento.

The Athletics’ players — sandwiched in between the two cities’ patches — are an up-and-coming group. After enduring a noisy exit from Oakland that was entirely out of their control, the group would love for the conversation to now center on baseball. Brent Rooker, the team’s best hitter, took a dutiful tone when asked about the relocation drama, then laughed a little when asked if he were ready for people to stop inquiring.

“Yeah, the exciting thing is that our team is going to be good enough this year to where it’s going to stop a lot of that,” Rooker said.

This spring, owner John Fisher and the team’s management group have also been eager to turn the page. That’s unsurprising given what they faced, and in many ways invited, in Oakland.

Fans in Oakland remain heartbroken, but a Sacramento community just 85 or so miles away will enjoy the novelty of an MLB franchise, even if “sell the team” chants are reprised from time to time. The A’s say they have sold out of season tickets at Sutter Health Park, about 6,000 of them in a 14,000-seat capacity stadium.

“The community there is incredibly excited to have professional baseball coming to it. It’s a sports-crazy market,” Fisher said. “Lew Wolff and I bought the team in 2005 knowing that we needed to build a new stadium. And it’s a little hard to believe it’s taken the time that it’s taken. But I feel like now with construction expected to start this June in Las Vegas, with the team starting out playing in Sacramento, it’s just a very exciting time for the team.”

Fisher is also starting to show some signs of life in roster spending, a relative distinction considering he has long carried a bottom-feeding payroll. In this calendar year alone the A’s have given long-term extensions to two of their best players, Rooker and Lawrence Butler, as well as one to their manager, Mark Kotsay. They even inked a recognizable free agent over the winter, pitcher Luis Severino.

But no one in the world of the A’s has yet escaped the discomfort of being in-between: not Fisher or the fans who still denounce him, not the staff faced with relocation and hotel stays, and not the players, who have already seen the ballplayer’s adage “control what you can control” tested to the extreme. The move to Sacramento changes the A’s reality but in different ways for each group.

Early this month, some of the most visible and vocal A’s fans — or former A’s fans — gathered in West Oakland for their annual Fans’ Fest. In the past, the event served as a kickoff for baseball season, as well as a rally against relocation. Jorge Leon, one of the organizers, said the message now is that fans have moved on from the team.

“To be honest, I have in some sort of way,” said Leon, who runs a fan group called the Oakland 68s, a nod to the team’s first year in the city. “What hurts more is the things that they lost here.”

The event was held outside the stadium of the Oakland Ballers, a pro baseball team founded in direct response to the A’s move, but connections to the A’s inevitably remain. The festival featured former Athletics stars Jose Canseco and Miguel Tejada, among others.

Anson Cansanares, another Fans’ Fest organizer, said he too is moving on but acknowledged not everyone will.

“Sacramento to Oakland is 80 miles,” Cansanares said. “You can get there in like an hour and 20, an hour and 30 minutes. There’s gonna most likely be people over there just trolling the A’s, just chanting ‘Let’s go Oakland’ when they’re trying to veer away from Oakland. We’re not saying to do that, but you can’t stop someone from doing it who bought a ticket.

“I think the A’s are over their head if they thought that, ‘Oh, we’re in Sacramento now, it’s over.’ It’s like, ‘No, it’s not.’”

Fans and the team’s brass might have more in common than they realize: both seek what’s next, yet the past keeps its grip.

“Hey, the response from our Bay Area fans is completely understandable,” Fisher said when asked about the vitriol directed his way. “Losing a team is a really difficult thing. As I’ve said before, I’ve been at this now for 20 years, and we’re super excited about where we are today.

“Does that make up for the sadness that exists in the Bay Area, for the A’s moving? Of course not.”

The exit from Oakland was so acrimonious that perhaps the only direction left for the A’s to go was up. Even so, Fisher said he sees real momentum building in his organization.

This month alone, the team started accepting deposits for priority access to season tickets in Las Vegas; reached a seven-year, $65.5 million deal with Butler, a 24-year-old who hit three home runs in a game last season and is also armed with speed and charm; hired a new team president, Marc Badain, who held the same role with the Oakland Raiders; introduced the Las Vegas patch sponsorship; and released new renderings for the $1.75 billion stadium in Las Vegas, which is backed by $380 million in tax dollars.

“We have a home and the ability to know where we’re going, and to build upon that,” Fisher said. “There’s an awful lot of positive things going on, and there’ll be more in the future.”

There’s no gripe to be had with the Butler deal, which comes on the heels of Rooker’s five-year, $60 million contract. Both players are part of a nucleus that could grow together heading into Las Vegas, finally giving the A’s the kind of long-term, standout cornerstones fans can grow attached to and root for. This offseason was the first Butler found he was being consistently recognized in public: “It’s kind of crazy,” he said.

Lawrence Butler’s extension is the kind of deal the A’s rarely made in recent years. (Thearon W. Henderson / Getty Images)

But there remains room for raised eyebrows in the list of recent A’s happenings.

On the field, while extensions are a step toward contention, the A’s haven’t been a .500 team since 2021. They have the talent for a surprise run, but they also are not commonly expected to reach the playoffs — despite optimism from Fisher akin to what most owners say during spring training.

“This isn’t a build to the future,” the owner said. “We think that we can win today, and that’s really our goal.”

Last year, the A’s finished fourth in the five-team American League West, an improvement from consecutive last-place finishes in the two prior seasons. They won the division in the pandemic-shortened 2020 season, but the 2018 and 2019 seasons were their last hurrah in front of fans in Oakland, with 97 wins each year.

Payroll projects to be $112 million, per Cot’s Contracts, tying the A’s with the Pittsburgh Pirates for the fourth lowest. The team’s big signing, Severino, received $67 million over three years — a pittance for a team like the Los Angeles Dodgers, but the largest salary guarantee in A’s history.

But it’s unclear whether the commitment to Severino was made out of ambition or obligation. Had Fisher and general manager David Forst not reached roughly $105 million in salary this year, they would have put themselves in danger of a grievance from the players’ union over the team’s use of revenue-sharing dollars.

In most ways, the A’s are about the future, and how much the team spends in subsequent years will be more telling. Fisher said he plans “to continue to build the payroll.”

On the field, the A’s should be better. The field itself, though? That’s brought its own set of challenges.

The Major League Baseball Players Association successfully pushed the A’s and MLB to change a plan to install artificial turf at Sutter Health Park and to choose grass instead. The turf would have been more durable, an advantage with not one but two teams using the stadium. The Sacramento River Cats, the Triple-A team of the San Francisco Giants and the park’s regular inhabitants will play their home games there when the A’s are out of town.

The A’s have made improvements to Sutter Health Park, but it was never intended to host major-league games. (Rich Pedroncelli / Associated Press)

But Sacramento temperatures run significantly higher than Oakland in the summer, and turf will also would have made an already hot playing environment hotter, because it retains more heat than grass. How players fare in the heat, and how the A’s and visiting players alike find their accommodations at a renovated minor-league stadium, are open questions to start the season.

“There’s a lot of investment that was done in facilities that you just would not have done otherwise,” MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred said. “The ballpark is charming. I do think that fans are going to have an opportunity to see Major League Baseball all season long in a really intimate environment.”

The players may find that intimacy less attractive. Players work their way through multiple levels of the minors to feel as though they are in a big-league venue. Now they find themselves back where they started, through no fault of their own, which could lead to disappointment.

“Even if that does exist, it can’t matter and it can’t affect us, because it’s the situation that we’ve been given,” Rooker said.

But for all the A’s have done to the park, and for all the stoicism the players might display, one basic fact looms large. As Tony Clark, the head of the MLBPA, said, the A’s are “a major-league team playing in a minor-league facility.”

In their final years in Oakland, players could feel the pain of both fans and staff.

Starting pitcher J.P. Sears, who is in his fourth year with the team, said he and his teammates learned well how to compartmentalize their thoughts and focus on their task. They’re not unfeeling cinder blocks, though. Last season, Sears would sometimes lend an ear to the Oakland staff members he saw every day at the stadium.

“You feel for them because they don’t know what job they’re going to have in a couple months,” Sears said.

The move to Sacramento upends the lives of both full-time and seasonal workers, most of them outside of baseball operations.

Sandy Dean, a minority owner who served as interim president this winter, said the team is handling hotels and travel expenses for some employees. “We’re navigating something that’s unusual,” he said.

However, some staff will not follow the team, and even those who do might regard their stay as only temporary. Going from Oakland to Sacramento is one thing; California to Nevada is another.

Inside every baseball club, the group that manages the roster is always in something of a different world than the rest of the organization. Forst said that about 90 percent of his group in baseball operations is spared from the move’s disruption.

“Most of them, (Kotsay) and the coaching staff, player development, scouting, they live elsewhere,” Forst said. “I have a small group that is in the Bay Area that is absolutely affected by it, and that’s been difficult.

“It’s been hard to keep morale up because frankly, not everybody’s sure they want to move their entire lives for three years to one place and then have to move it again. So I will say, we’ve lost a couple people in baseball operations because of it. I don’t blame them at all.”

For as much change as the A’s face now, and for as much turmoil as the organization has seen, they have enjoyed a sense of continuity in leadership. Forst has been in Oakland for a quarter century, a holdover from the era of “Moneyball” and famed executive Billy Beane. This year is Forst’s 10th as the top baseball decision-maker.

“What if I said it felt like 30 years?” he joked.

The team’s relocation has bled into Forst’s friendships. Forst said that people close to him have asked, “What the hell are you doing? Why are you doing this to the community?” He understood it, but it was exhausting. Yet, he hasn’t fled to another organization where there might be less tumult. He said he has stayed because he loves the people inside the organization, and because his family loves the Bay Area.

Kotsay, meanwhile, saw how plenty of other teams do business while playing nearly 2,000 games as a big leaguer, including 472 with the A’s. He came back to the team as a coach in 2016 and took over as manager in 2022. He just signed an extension through 2028, the planned opening year in Las Vegas.

“If you ask everyone that’s been in this organization — let’s just use five years — that has left this organization, they will tell you there’s no better environment, no better place,” Kotsay said.

The relocation saga forced Kotsay into a particularly difficult position. Required to speak to the media every day of the season, and to walk a tightrope when responding to fan anger or management decisions, he nevertheless retained the respect of the players, the fans and management. He is perhaps the one thing all three groups can agree on.

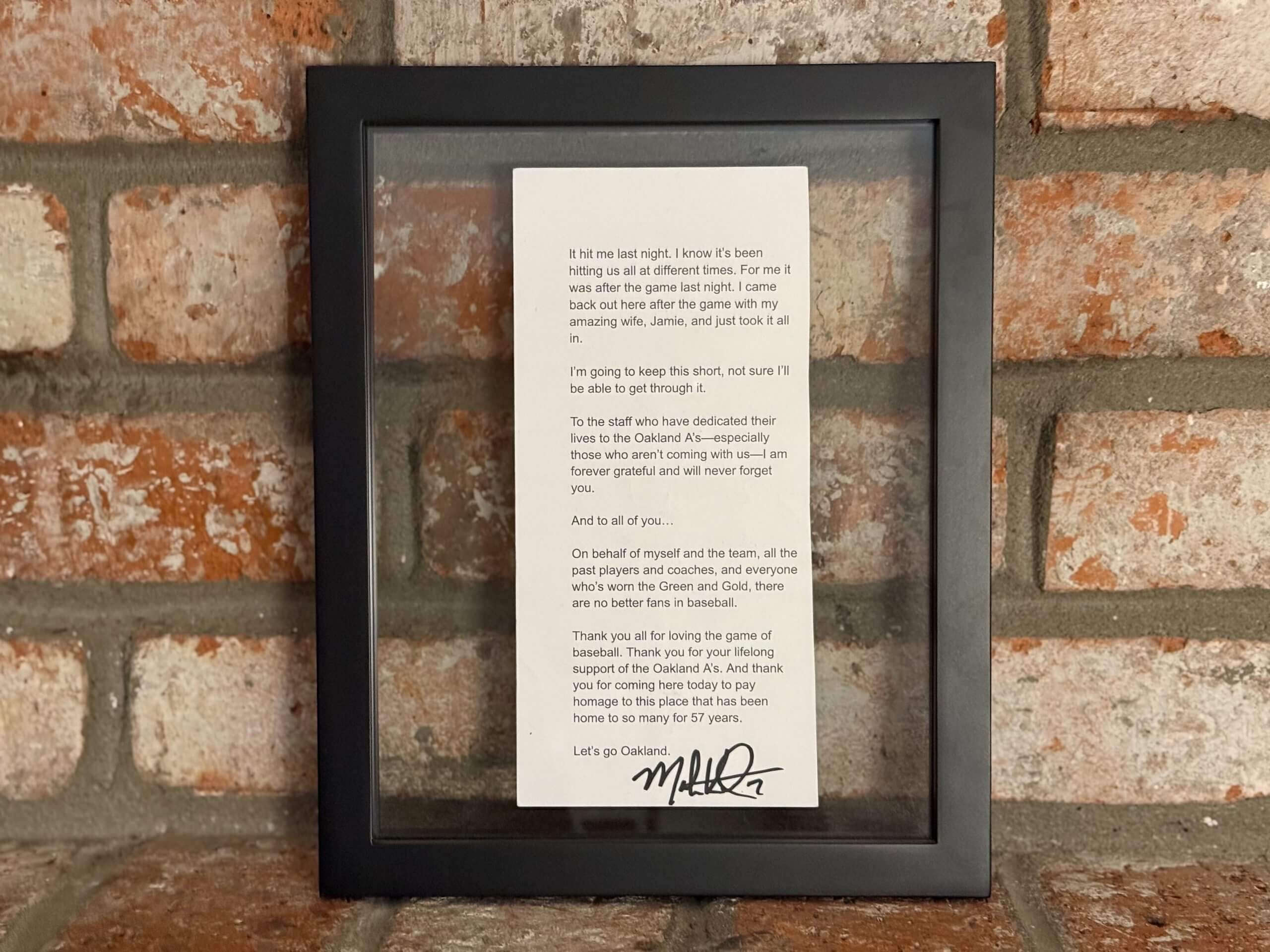

In taking on that singular role in a delicate process, Kotsay made himself part of A’s lore. His three-minute speech after the final game at the old stadium, the Coliseum, helped salve some of the pain, if only briefly. He wasn’t even sure he would say anything until late the night before.

The idea originated about a month earlier when Kotsay took his wife and son to a California burger-and-shake chain, Fosters Freeze in Danville. Two fans dressed in team gear were eating in the restaurant.

“I don’t know if these two gentlemen will read this,” Kotsay said. “I actually engaged them. I was like, ‘Hey, do you guys think something needs to be said?’”

They did. When the day came, Kotsay raised his voice only once. “There are no, better, fans …”

Two A’s employees have framed copies of the speech hanging in their homes.

The text of Mark Kotsay’s speech following the final game in Oakland. (Photo courtesy of Jennifer Ling)

The A’s are still the team that produced “Moneyball,” and that means they still might be the most influential baseball franchise of this century. They are the germ of the efficiency-minded modern-day front office, and that distinction makes the acrimony of Oakland almost more tragic. A revered franchise devolved into something that just made a lot of people want to yell. They weren’t even good at baseball anymore.

“It’s impossible not to recognize that we’ve been sort of an afterthought as far as the industry is concerned the last few years,” Forst said. “I don’t think any of us are out there seeking relevance or looking for accolades, but you’re right: there was a long stretch where we were very relevant, whether it was ‘Moneyball’ or our teams in the 2010s that were making playoff runs.

“I think it’s been hard on morale in general. We’re looking forward to being in the mix again.”

Sacramento is an opportunity, but a tricky one with one foot out the door.

The team’s uniforms this year have a couple of other notable features. They will actually feature three patches: the two cities, plus one honoring Rickey Henderson, the Hall of Fame outfielder who died days before Christmas.

What the A’s will not do, however, is wear “Sacramento” across the front of their jerseys on the road, bucking the sport’s standard practice. That’s because Fisher and company explicitly want the team to be known as the Athletics or the A’s — not the Sacramento A’s, and not the Sacramento Athletics.

For years now, fans and media have questioned whether the stadium in Las Vegas will actually come to fruition. Fisher’s group wants to make sure people know they’re serious about Las Vegas; for all their excitement about Sacramento, the jersey reinforces that the city will never be more than a stopover. But that speaks to a decision ultimately made defensively — proof that the criticisms from fans in Oakland still resonate.

Leaving the Coliseum brings some sense of resolution. A year ago at this time, it wasn’t clear what city the 2025 A’s would play in. Sacramento was a front-runner, but no decision had been made.

“The relief is that that stuff is out of the question now,” Sears said. “There was a lot of things that you might randomly think about sometimes.”

But the team’s no-strings-attached affair with Sacramento doesn’t exactly simplify things. Over the winter, Sears kept hearing the same question from family and friends.

“Y’all gonna be in Vegas this year?”

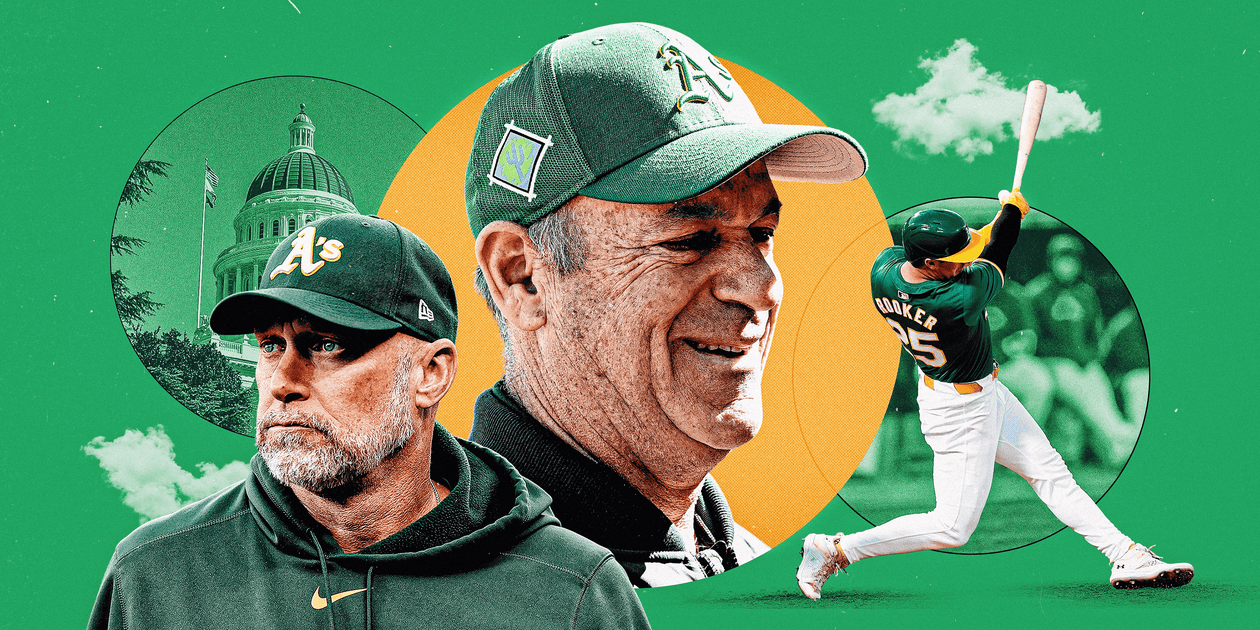

(Illustration: Will Tullos / The Athletic; Photos by David Paul Morris, Candice Ward and Thearon W. Henderson, Steph Chambers / Getty Images)