A few years back, on a flight going somewhere, Matt Berninger, the singer-songwriter and frontman of The National, had an idea, maybe even a good one.

Thus began a search. Berninger patted himself down, dug a hand into seat pockets and any bag he could find. No notebook. Resorting to his cell phone, he tapped the screen. No luck. Dead battery.

The search wasn’t frantic, but it was a bit desperate. At the time, for Berninger, such a moment, and such an idea, was hard to come by. Writer’s block. Creative paralysis. Whatever you want to call it. Berninger was deep in it; had been for a while. And now here he was with this passing thought, something out of nowhere, something worth writing down, but nowhere to put it.

Berninger pushed open a tote bag. There he came upon some old travel companions. For years, from The National’s early days through its ascent to one of the biggest bands in rock, Berninger toured with a baseball and glove as weapons against monotony. When needing a break, he and a bandmate, maybe one of the Devendorf brothers — Scott, the bassist, or Bryan, the drummer — would slip out a side door to play catch. Something about the pop-pop of a ball back and forth helped clear the mind when the mind needed clearing.

Berninger leaned back in his seat, studying the ball, running his thumb over the grain, across the stitching, against the scuff marks. A baseball has weight to it. About 5.25 ounces. Substance. Finding a place for his idea, he pushed a pen onto the rawhide, rotating the ball as he went. For reasons he’d only come to unpack and understand later, it all felt right.

“I just thought, man, this is f—ing cool,” he says.

The words kept coming. So Berninger kept writing.

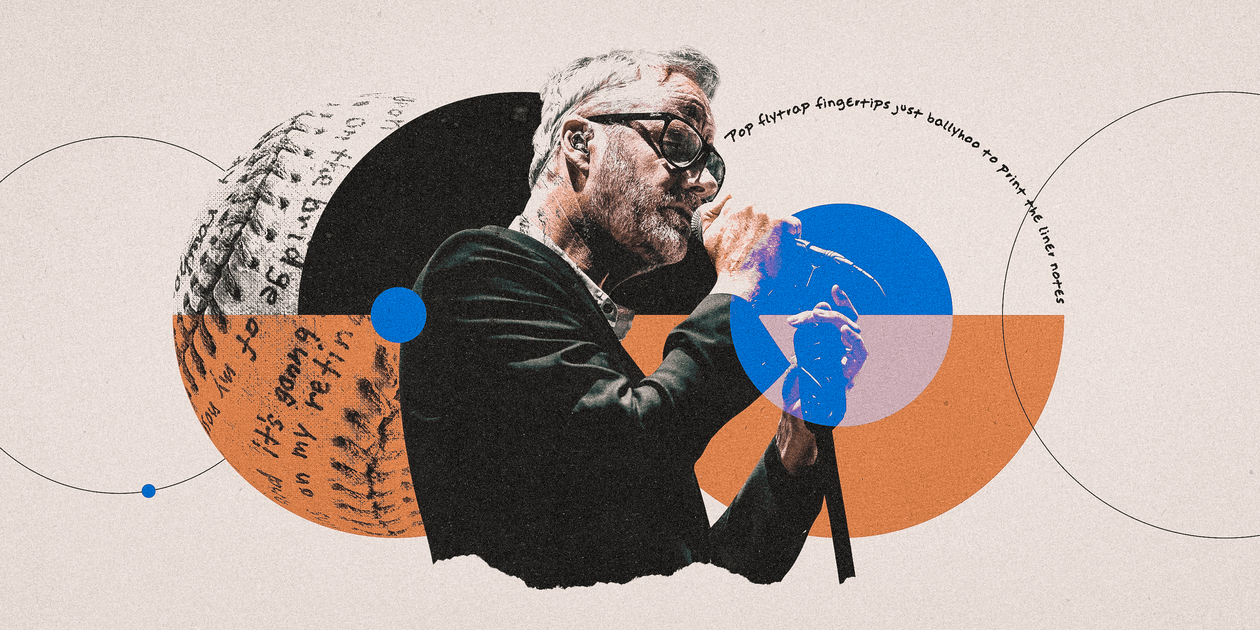

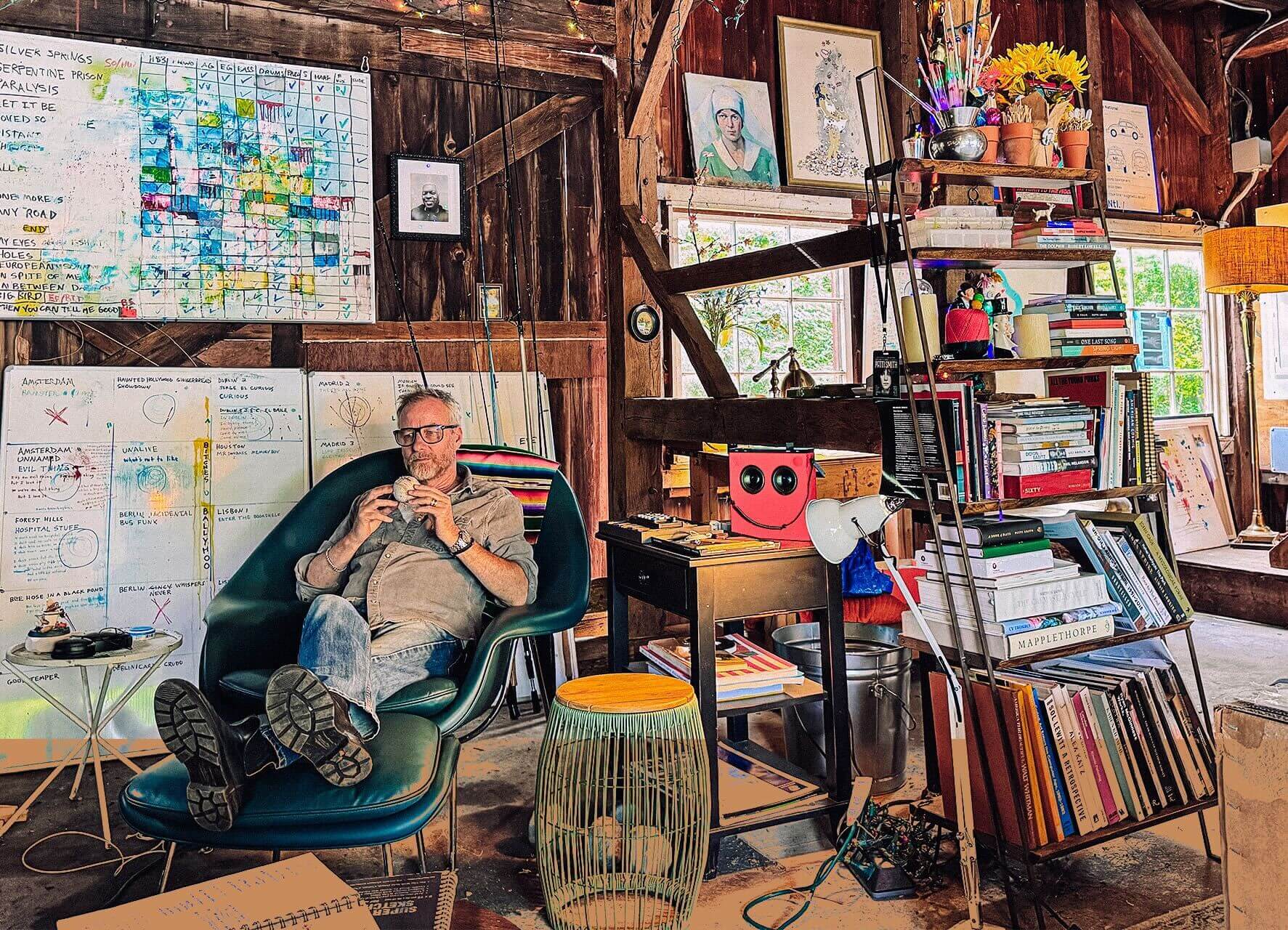

Matt Berninger, reclining in his Connecticut workshop, doesn’t just talk. He unspools. Brendan Quinn / The Athletic

There’s a garage, a garage that centuries ago was a barn, a barn that is now something else entirely, some kind of Daedalian lab. Paintings, plants, sculptures. Christmas lights, art books, unfinished projects. A row of old wrestling figurines forms a battle line across a joist. On the ceiling, an upside-down umbrella dangles as a lampshade. The sliding door is open, sharing the space with the world outside — a winding rural Connecticut road, the nearby woods where he roams, a seafoam green house with a stone foundation dating to 1760 and a brick chimney surveying the land. This is where, at 54, Matt Berninger is his other self.

Fans know the baritone version in the black suit and black glasses; on stage and on the brink. That one wrings every letter out of every word, extending a hand to push everyone away, then looking for arms to fall into. Berninger does not sing songs. He pours forth.

This version? Berninger is a suburban dad to a 16-year-old daughter. When a hack writer pulls into the driveway one day to spend an afternoon, his wife, Carin Besser — the inspiration for, and co-writer of, numerous National songs — nudges the front door of the house closed without ever being seen. A former fiction editor at The New Yorker, Besser has spent much of the last 20-some odd years attempting to explain her husband to those who want to understand him. This will not be one of those days.

Berninger emerges from the garage in jeans and a gray corduroy shirt. Thematically, an avatar of a New Englander in autumn. In actuality, an erstwhile bohemian, unsubscribed from city living.

“We’ve been in Connecticut for about 2 1/2 years,” Berninger begins, heading into the garage, “but we moved into this house just last March. I basically just moved all my s— in here. It’s a … a workshop, I guess.”

Speaking to an audience of one, Berninger doesn’t talk; he unspools. He explains, then expands, then illuminates. If you let him go, he goes, and you go with him.

We begin in the past. It resides in rows upon rows of manila envelopes, clasped shut. Sliding a bin out from under a craft table, Berninger grabs one. “So this was ‘High Violet,’” he says, referencing the band’s 2010 album, the one of “Terrible Love,” “Bloodbuzz Ohio,” “England,” and others. He thumbs through notebooks and sketchbooks. Some pages amount to little. There’s a drawing he doesn’t recall. There’s a random list of words.

Flake

Feel

Freeze

Pills

March

“OK, here is where I’m starting to put something together,” he says, stopping on one page. “So, this turned into a real song.” In front of him, Berninger points to the original lyrics to “Vanderlyle Crybaby Geeks,” a song that, 15 years later, remains The National’s closer. Atop the opposite page, “Vicious Wishes” stands alone.

“Wrote a title, never wrote the song.”

Berninger used to love notebooks. Crowded, fraying, well-traveled notebooks. All loosely organized with a system of colored underlines and dots. As a younger man, he’d roam down hallways and streets, writing and writing. He’d hunch over a bar, scribbling words and filling ashtrays. An unending torrent of ideas, lyrics, poetry. As the writer Ryan Pinkard once put it, when Berninger did stand still, he could be found writing while “bent in strange positions like an antenna trying to pick up a signal.” Today, each notebook feels like a bottle in a cellar of another era — Brooklyn, late ’90s, early aughts, the indie music scene explosion.

Berninger moved to New York in 1996 to chase a career in graphic design, but instead formed The National alongside two sets of brothers — the Devendorfs and twins Aaron and Bryce Dessner. All five hailed from Cincinnati, but came together in a loft apartment at the dead end of Bond Street, back against the Gowanus Canal.

The impulse, for Berninger, was always to write in the void between light and dark. We don’t get to decide where we’re from, but he chose to be a descendant of Tom Waits, Leonard Cohen and Nick Cave. Lyrics from the perspective of the lover and the loner, of the heartbreaker and the brokenhearted, of the also-ran and the egoist, he found his voice. Poetic, but relatable. He wrote of “another un-innocent elegant fall into the unmagnificent lives of adults,” and being “mistaken for strangers by your own friends,” and declaring, “So sorry, but the motorcade will have to go around me this time.”

“He started more introverted — more of his personal universe,” Scott Devendorf says today. “That still exists, but it’s grown over the years — people, places, experiences multiply, and his writing has followed.”

Berninger and The National went from playing empty clubs in their earliest days to touring with R.E.M. following critical acclaim for the 2007 release of “Boxer.” In time came the moments that all bands imagine, but few find — commercial success on sales charts and in box offices, collaborations with Taylor Swift, a status as patron saints to middle-aged men with emotional impairments. Berninger released the title track for his first solo album, “Serpentine Prison,” in early 2020.

And just as everything came together? That’s when Berninger came apart. Clinical depression coincided with the pandemic. A state so severe he was bedridden and, he says, “almost to the point of being nonverbal.”

“I didn’t know how to be a happy person,” Berninger says. “I had to see what it’s like to be at the very bottom. Because I write about looking at the bottom all the time, and I write about looking over the abyss, and then I found myself at the bottom. A part of me was like, why have I always been so f—ing obsessed with being at the bottom? I wondered, did I put myself here to learn more? And no, that wasn’t it. In truth, it happened to me. Depression sneaks up on you.”

Sitting in the corner of his garage, sunk deep into an Eames-style chair, Berninger relights a dormant joint and thinks about those days — not the throes of his depression, but the aftermath; a time when what once came so natural to him — writing — felt like pressing hands against the walls of a dark room looking for a light switch.

“At that time, I started getting depressed by notebooks,” Berninger says. “Whenever I’d see a notebook or an empty white page, it started to become a feeling — like, ah, there’s this thing I have to do. All these cool notebooks, I used to love them, but then they became such a part of my job. In a funny way, I started having a little bit of contempt (for them). All I thought about was my notebooks and all the work I needed to work on.”

What Berninger needed was somewhere else to write. He just had to find it.

Matt Berninger was born on the westside of Cincinnati in 1971, a time and place so subscribed to baseball that the Big Red Machine — the superhero subtitle for the impossibly talented teams of Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan, Pete Rose and Tony Perez — remains part of the nomenclature not only in southeast Ohio, but across baseball. Growing up, Young Matt felt about baseball the way every kid in Cincinnati felt about baseball: that the entire universe, and every passing breath, revolved around the Reds.

Radios were perpetually tuned to 700 WLW. Clara Berninger, Matt’s grandmother, listened religiously. They weren’t the Reds. They were her Reds. Quaint and quiet at all other times, she’d holler at any error committed or any run allowed. “Oh, you clunker!”

Dad listened when working in the yard or in the garden or in the garage. Paul Berninger loved hunting, fishing and camping (still does), but always had room for baseball. He coached Matt’s tee-ball team and got tickets to a few games a year at the new Riverfront Stadium. Father and son would watch Pete Rose fly around the field, careen into second base, get up and shake the dirt from the folds of his jersey. There’s no more indelible image of Cincinnati in the ’70s than that. Except then Paul would lean over to tell his son about the Pete Rose he knew. See, Paul grew up not too far from Pete, in the Western Hills section of the city. The two worked at the same golf course as teenagers. One night, the story went, when Paul was trying to close the caddie shack, Pete came in, demanding a candy bar or something. Paul told Pete the shack was closed. Pete, according to Paul, responded by urinating on the counter.

“They didn’t exactly get along,” Matt says.

Paul worked as a city attorney, but made it home by 6:30 to play catch. The two would head into the backyard, tossing a baseball — dad lobbing it, son throwing it. The stuff you tend to remember later in life.

“Think about a parent and a child and the weight of a baseball, you know what I mean?” Berninger says. “It’s a scary thing as a little kid to throw a hard baseball back and forth. But you do it and you get better at it. Maybe you get hit by the ball, but you keep going. Eventually, you’re there, you’re with your parent, and you’re talking; talking about everything, the stuff you might not talk about at the dinner table or on the way to school. Tossing a baseball, it all comes up.”

Matt played shortstop in Little League. The ’70s turned into the ’80s and he thought he’d play forever. “Absolutely loved it,” he says. One day a coach told Matt, “You’re the next Dave Concepción!” and, if you’re wondering what that meant to an 11-year-old in Cincinnati in 1982, well, “I still remember it to this day,” Matt says in a garage 43 years later.

Eventually, though, as it does, time turned unsentimentally. Games turned into something different. Better players appeared. Matt was sent to the outfield. What was once playing turned into self-preservation.

“I got out when it got serious and people started yelling at each other,” he says. “I didn’t want to piss off a bunch of people by missing a catch.”

As kids do, Berninger left his feelings on the diamond and moved somewhere he could survive. He found the art department, navigating the strangeness of teenage life by leaning into his parents’ passion — drawing, painting, creating. While friends listened to hard rock and glam metal, he poached music from his older sister and plugged in headphones playing U2, The Smiths and The Cure. Though he took piano lessons and strummed a few guitar strings, he never found an instrument that fit, something he chalks up to “a weak left hand.” Instead, as Berninger puts it, “music and art and writing all sort of became the same thing for me.”

Baseball, meanwhile, was packed away, stored in a corner, like an envelope in a bin.

“You can change your traumas, the things that are weighing you down, your level of anxiety,” Matt Berninger says, back in the Eames chair, “by changing your pattern.”

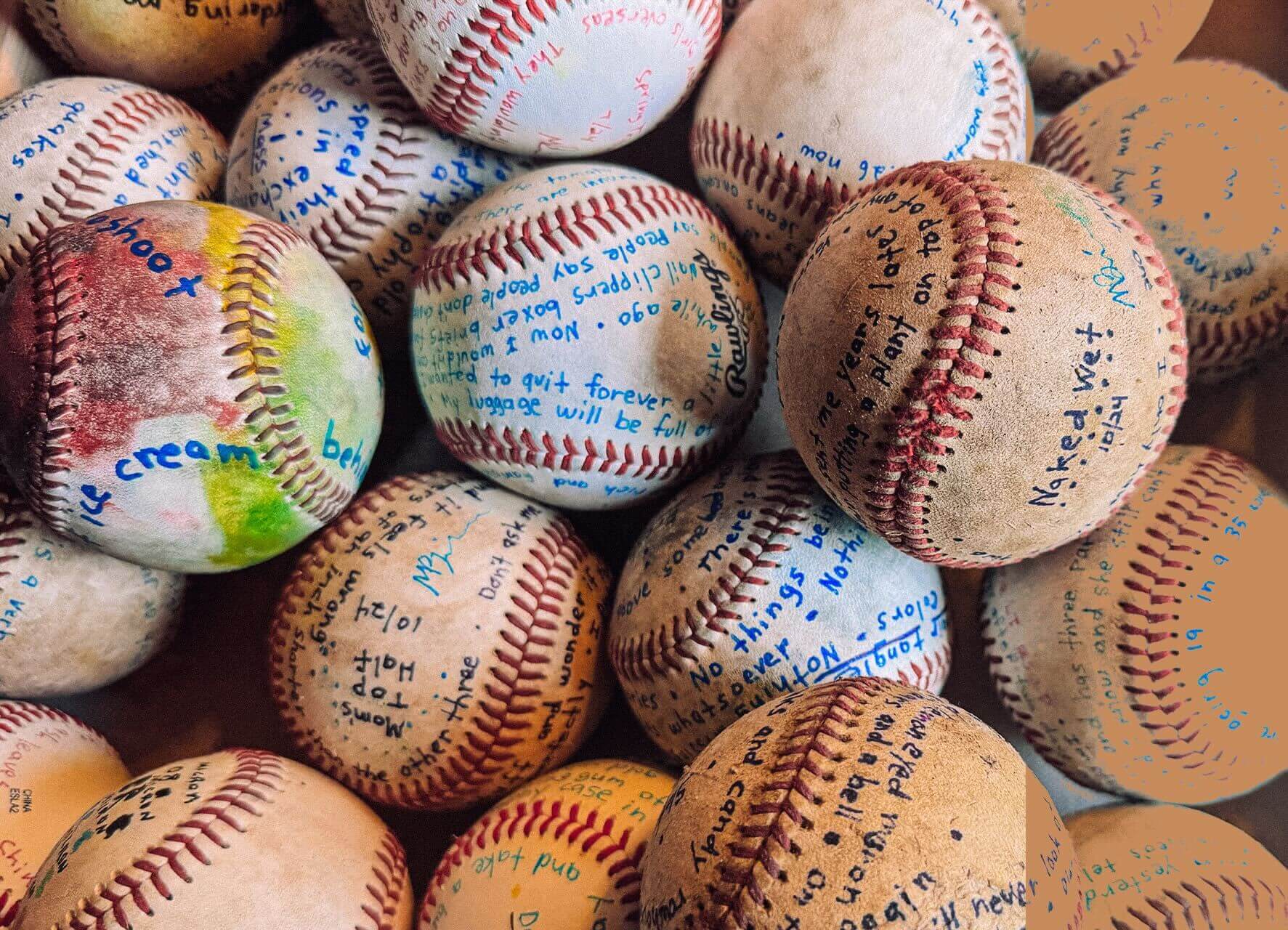

Berninger stands, then sits, before standing again. Near the front of the garage, dozens upon dozens of baseballs, some crisp white and lightly used, others beaten and browned, are covered in words. Clean penmanship, curling and coiling around each. On the floor is a box of old balls, blank. He orders them from eBay whenever he’s running low.

Picking a ball out of the pile, he reads what he wrote one day, not too long ago.

“Nineteen feet from the porch to the street. No one ever looks over.”

Berninger doesn’t remember what he wrote on that first baseball, nearly four years ago. All he knows is the wiring changed that day. His lyrics have long been born from flashes of thoughts collected in a variety of mediums — collages, book margins, a never-ending text message thread from him to himself. In recent years, for one reason or another, he needed a new medium.

“When you’re writing in a notebook or even on your phone or your laptop, there’s a line spacing,” he says. “There’s a linear stacking of lines and stuff like that. It starts to form the way you write.”

There is no structure to writing on a ball. There can’t be. Berninger starts under the Rawlings logo. One word leads to another. He moves along the stitching, turning the ball, every word rotating out of view, onto whatever comes next. He’s talking faster now, moving through the garage, explaining how the lyrics on a ball can marry with an idea on a collage and birth a song. The air in here feels different.

He wants you to try it. He hands you a blank ball. All you have to do is write whatever comes to mind, but we’re not all Matt Berninger.

“Matt thrives on chaos, especially on the stage, that kind of white-lightning energy that can only happen between a rock band and its crowd,” says Sean O’Brien, the Grammy Award-winning producer and engineer who has co-written songs with Berninger for years, dating back to The National’s 2017 release “Sleep Well Beast.” “Lately, I think he’s been trying to funnel that energy into his writer’s den and the studio. Not that he’s throwing a mic stand across the room or anything, but I think he’s trying out some new tactics to mix things up, surprise his collaborators and even surprise himself to find new ways to ‘cook,’ as he often says. I think being in motion helps.”

Berninger has decided that Pigma Micron 08 pens are the correct pens to write on a baseball. Clear. Legible. He lies on a couch, a ball looking back at him, and begins. The writing is loose, he says. “Gooey.” He doesn’t wonder what a song is going to be about. He mumbles words, inviting whatever wants to come out, to come out.

“It’s almost like you’re walking into a scene and you’re not sure of the setting,” he says. “Is it a Scorsese movie? Is it a Jane Campion movie? The music is telling you what room you’re in, and then you just sort of start to imagine, and let go of your brain, and find melody.

“Once you find a good melody, and you repeat it, words will start to stick to that melody. A good melody is like flypaper. Words, phrases, sounds of words will stick to it, and then you’ll find yourself writing, and, oh, you’ll get a whole phrase in.”

He isn’t sure how many balls he’s written on, or how many he’s given away, or even how many songs have been spawned.

Pulling a plastic bag off the wall, Berninger reaches in and pulls out what looks like the remains of a nest. A deconstructed baseball is made up of two pieces of white leather, a red string, a layer of sticky white string, some gray stuff, and a red rubber ball.

“No different than all the elements of a song,” he says, holding up the entrails.

These are Berninger’s notebooks now, and the words are changing with them. O’Brien has seen, what he calls, an evolution, as if Berninger has left versions of his past self behind.

“His stories in the songs are becoming more surreal and less easy to pin down to one time or place,” O’Brien says. “It’s been interesting seeing him challenge himself to use less words and paint the picture with fewer details. Like a scribbled journal entry the morning after a fever dream.”

Maybe that’s what comes when the words go round. Booker T. Jones, the legendary producer and arranger, worked with Berninger on both solo albums, “Serpentine Prison” and “Get Sunk” (2025), both before and after Berninger reimagined how to make his words work, and says he had no idea about the baseballs. Jones says he’s always thought Berninger’s lyrics are shaped by “a huge imagination” and “word pictures of individuality and unpredictability” and have only been getting better.

“I guess everyone needs to find their baseball,” Jones says.

Matt Berninger isn’t sure how many balls he’s written on, or how many he’s given away, or even how many songs have been spawned. Brendan Quinn / The Athletic

On the right side of the garage, next to a picture of Berninger and Patti Smith, is a photo of him and Dave Letterman. In October 2023, the two came together for a shared conversation about their struggles with depression. Recorded about two years after Berninger’s darkest days, Dave tells Matt that one of his favorite lyrics is the mention of “pharmacy slippers” in “Smoke Detector,” a song off The National’s 2023 bonus release, “Laugh Track.” Letterman read the whole line: “Sit in the backyard in my pharmacy slippers. At least I’m not on the roof anymore. In a year or so, I hope nobody remembers.” The two shared a laugh about it.

Under the photo is a Cincinnati Reds hat.

There’s a sort of freedom in consuming baseball the way Matt Berninger consumes baseball. He is not a fan, at least not in the rah-rah, Go Reds!, who’s a free agent?-sense. He didn’t realize this year’s Reds made the playoffs. He hasn’t been to a game — any game — in years. He has no idea who won last year’s World Series and likely doesn’t know who’s playing this time around.

Yet the game has always had a place.

When writing, Berninger likes to put a muted game on the television. A background diorama. It’s the symmetry of the diamond, the bodies on the field, the unspoken words between pitchers and catchers. “It’s like Kabuki theater,” he says. “The looks, and the eye contact, and the signals, and the espionage. It’s so theatrical and dramatic.”

When painting or drawing, Berninger occasionally finds a game on satellite radio and plays the audio on his phone. He doesn’t care who’s playing. It’s a white noise of balls and strikes. “The atmosphere, the rhythm, the drama,” he says. “What’s great about baseball is there’s so much time to talk about the human stories.”

That Cincinnati hat? In a workshop built by the farthest corner of his mind, and pulled from the collected works of a sidewinding career, it’s an homage to how Berninger got here. He pulls for the Reds only because, if she were here, it’d make his grandma happy. Part of him, a tiny part, probably still wishes he was Dave Concepción.

Moving again in the garage, Berninger goes back to the baseballs. Some have already become songs. Others will in time. Feeling around the pile, picking up one, then another, reading what’s been written, he says that, of late, he’s been writing on balls less and less. “I’m kind of like, OK, I’ve done that, I’ve gotten a lot out of that, but I don’t know if I need them anymore,” he says, looking up, making sure you’re following. “It’s just, like, nice to know I can still always go back to these, you know?”

Hearing all this, you have to wonder: What is it about baseball that makes the stitching last?

Maybe that’s a thought to write down. For now, Berninger is hoping his daughter gets home soon. He wants to head out back for a catch.