At least there’s one good thing that comes with the unfortunate end of every baseball season:

It’s now Hall of Fame season!

We got the first reminder just this week, when the Hall revealed the eight names that will appear on the Contemporary Baseball Era ballot next month. And it’s as intriguing a group as we’ve ever seen on one of these era committee ballots.

Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens are back. So are Don Mattingly and Dale Murphy. There’s so much to talk about and think about with those four names alone.

Then there are the four first-timers: Gary Sheffield, Jeff Kent, Carlos Delgado and, in a minor surprise, Fernando Valenzuela. There’s a definite case for — and against — every one of them.

They’ll be voted on when the 16 still-unnamed members of that committee meet in Orlando on Dec. 7. As always, a candidate needs 75 percent — in this case, that’s 12 votes — to be elected. Who will clear that bar? It’s pretty much impossible to predict. So here come Five Things to Watch on the Contemporary Era Ballot.

1. Bonds and Clemens: Still the elephants in the room

Is there a place in the Hall of Fame for Barry Bonds? (Stephen Dunn / Getty Images)

They’ve become the faces of the entire performance-enhancing drug era. So the baseball world will be watching closely to see if Bonds and Clemens gain any traction in this election.

When they appeared on the ballot for the first time three years ago, it felt like more than a case of two candidates falling short. It felt almost like a repudiation.

There were 16 voters in that room. Bonds and Clemens couldn’t even attract four votes apiece. If that happens again, they wouldn’t be allowed to appear on the ballot the next time the committee meets in three years, thanks to a new set of rules that we’ll discuss shortly.

Obviously, you never know how any of these era committees, formerly known as the Veterans Committee, will vote. Marvin Miller got the thumbs-down seven times before being elected six years ago. Dick Allen fell short six times, then got elected last December.

So we know that years go by, perspectives change and the faces in the room change. But it’s at least possible that we’ll look back on this someday and realize the best shot Bonds and Clemens ever had of being elected was in their 10 years on the baseball writers’ ballot.

They both topped 60 percent — and more than 300 votes apiece — on that ballot. Three years ago, they couldn’t even top three votes on this committee’s ballot.

Take a step back and remember that Bonds hit more home runs (762) than anyone who ever lived. Clemens won more Cy Young awards (seven) than any pitcher who ever pitched. If we use Baseball Reference’s wins above replacement as a barometer, they’re two of the top eight players in history. So if they never make it into the Hall, think about what it means.

The top 85 eligible NBA/ABA players in history are all in basketball’s Hall of Fame. The top 20 eligible NFL players in history are all in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

But baseball is different. In general, I think we should applaud that. But will historians look back on this 100 years from now and ask: What kind of Hall of Fame has no place in the plaque gallery for two players like Bonds and Clemens? Sure sounds like the kind of question historians ask.

2. Mattingly and Murphy: Is it time to honor character and integrity?

Don Mattingly received eight of the 16 votes in his last time on this ballot. A candidate needs 75 percent — 12 votes — for election. (Ron Vesely / MLB Photos via Getty Images)

Character. Integrity. It’s easy to understand why voters weigh those traits when it’s time to choose, say, the Nobel Peace Prize. But where do those qualities fit when we’re voting on Hall of Fame baseball players? The voters have been trying to figure that out for decades.

They honestly have no choice, you know. They’re told, in the voting instructions, to consider integrity … and sportsmanship … and character, right there alongside the numbers. So why are men like Bonds and Clemens not in the Hall of Fame? In large part it’s because that character-and-integrity thing is a reason some voters chose not to select them.

But rarely have voters taken the opposite stance, and used character and integrity to award extra points to players whose class, grace and professionalism gleamed brightest throughout their careers. Not sure why that is, but here’s why I bring this up:

Because Yankees icon Don Mattingly and the onetime face of the Braves, Dale Murphy, are back on this ballot. And for about a decade and a half, both were shining examples of everything this sport should want its stars to be. Maybe their uptick in the voting three years ago was a sign this committee recognized that.

Mattingly got more votes (eight) in the last election than anyone except Fred McGriff, who was elected unanimously. That’s 50 percent — nearly double the highest tally he ever received in any vote by the writers (28.2 percent).

Murphy got six votes, or 37.5 percent. That also tops his highest percentage in any of the 15 years he logged on the writers’ ballot (23.2 percent).

But it’s also fair to wonder if there was another force at work. Hall of Fame elections used to be driven by the magic counting numbers of baseball — 3,000 hits, 500 homers, 300 wins … you know that drill. In recent years, though, we’ve seen a different trend, as those big counting numbers become more and more scarce.

We’re seeing movement toward players who have a different appeal: Big peaks are now getting these voters’ attention. Longevity … not so much. So could that help Mattingly and Murphy — two men who lack those round numbers but once spent a few years in the “Who’s the best player in baseball?” conversation? We’re about to find out.

3. How will the first-time candidates fare?

Gary Sheffield garnered 63.9 percent of the vote in 2024, his last year on the writers’ ballot. (Mark Cunningham / MLB Photos via Getty Images)

Sheffield … Kent … Delgado … Valenzuela. Those are four great names that have never been considered by any of these committees before. But they’re also four names that had very different journeys on the writers’ ballot.

Sheffield and Kent — These two took a 10-year ride on the Baseball Writers’ Association of America ballot train, and both made significant surges in the voting in their final year. Sheffield jumped all the way to 63.9 percent, just 43 votes short of election, in his 2024 finale. That was a huge development.

Did you know that, if we don’t include players currently eligible for the Contemporary Era ballot, every player in history who cleared 60 percent on the writers’ ballot eventually got elected by one of these committees?

Kent, meanwhile, made it to 46.5 percent in his last election (2023). Here’s what seemed noteworthy about that: He got exactly as many votes that year as Carlos Beltrán, who is now so close to delivering his Induction Sunday speech, he could get elected by the writers as soon as this winter.

Under ordinary circumstances, these would be two guys who are made to order for this committee. Sheffield hit 509 home runs. Kent hit more homers than any second baseman in history. Remember, about half of this 16-person committee will be made up of former players. Those numbers are talking their language.

On the other hand, there are reasons the writers never elected them. Full disclosure: I voted for both. But I’ll admit that with Sheffield, it took me a while to convince myself to vote for possibly the worst defensive outfielder in history. And I never knew what to make of his hazy ties to Bonds and BALCO, which were never fully explained.

And voting for Kent meant overlooking the fact that he finished his career with 42 Fielding Runs below average. But yeah, I looked past that — to cast a vote for the player who ranks No. 1 in homers, RBIs and slugging among all second basemen whose careers began in the live-ball era.

So they’re both really compelling candidates on a jam-packed ballot.

Carlos Delgado could be the best player ever to go “one-and-done” on the writers’ ballot. (Jeff Gross / Getty Images)

DELGADO AND VALENZUELA — The best part of these committees is that they provide a second chance for players like this, who never got a long look from the writers. I’ll be very curious to see how they fare in this election.

I once wrote that Delgado was the best player in history to get booted off the writers’ ballot after just one election. I’ll stand by that.

How many players have ever been one-and-done after hitting 473 homers? One. Just him. How many players with 2,000 games played and a .929 career OPS were one-and-done? One. Just him. How many players ever had a .900 OPS (or better) nine years in a row and were one-and-done? One. Just Carlos Delgado.

You think that had something to do with the fact that in his only year on the ballot (2015), there were 13 future Hall of Famers, plus Bonds, Clemens, Sheffield, Kent and Mattingly? Probably a related development!

Then there’s Valenzuela. It’s incredible that he has been retired for 28 years and he’d never made it onto one of these ballots before. But the sadness of his death last year has allowed all of us to refocus on how special he was in his moment in time, back when he was electrifying Dodger Stadium in the early 1980s.

His career numbers (173-153, with just a 104 ERA+) don’t truly tell the story of Fernandomania, a frenzy over one pitcher and his lovable brilliance unlike any in the last 50 years. If we’re going to be drawn to guys with big peaks, it isn’t hard to see a parallel between 1981-86 Valenzuela and 1980-87 Dale Murphy. Plus, Valenzuela’s unique charisma changed everything about the way Mexico — and Mexican Americans — felt about baseball.

So the vote totals for all of these first-timers will be truly fascinating.

4. Schilling, Evans, Whitaker and the men missing on the ballot

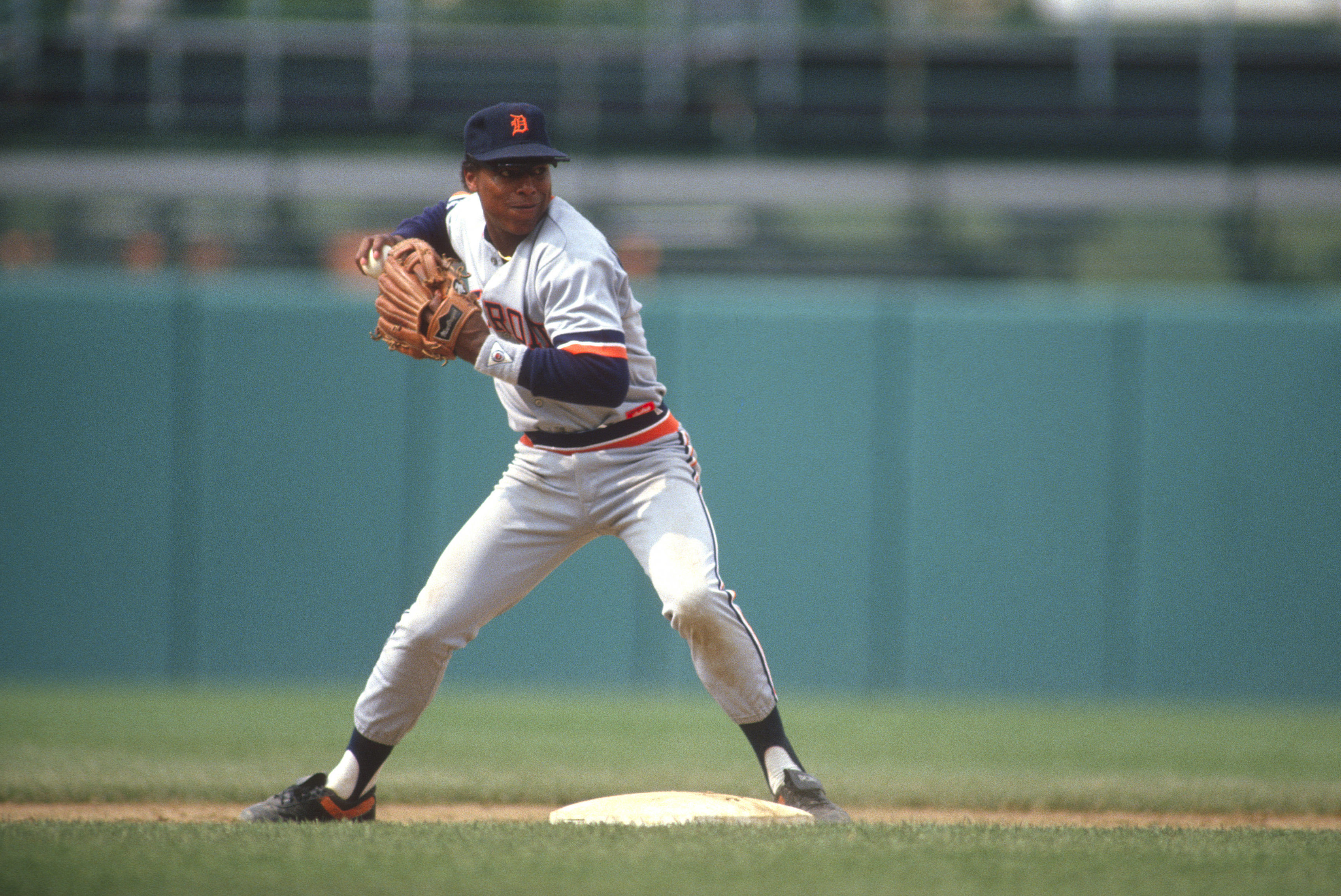

Lou Whitaker was among the notable names not on the ballot. (Focus on Sport / Getty Images)

I’ve never been a member of the Historical Overview Committee that has to decide which players make this ballot and which don’t. So I don’t know exactly how they draw that line. And I feel for them, because it’s so hard.

Nevertheless, there were as many big surprises in who wasn’t on this ballot as who was.

Curt Schilling — Not sure how he missed this cut, unless it had something to do with stuff that happened far away from any pitcher’s mounds. He got seven votes from this committee last time — more than anyone except McGriff and Mattingly. And he once collected 71.1 percent of the vote in a writers election — which would be (by far) the most ever by a player who wasn’t elected by one of these committees.

So he’s a puzzling omission. Schilling has had one strange ride on the Hall of Fame roller coaster, hasn’t he?

Dwight Evans — Here’s another one that’s hard to figure. Evans got eight votes in his last appearance on this ballot, six years ago. He now has missed this cut two elections in a row. That’s how overloaded this ballot was.

Other than Mookie Betts, who is still playing, no right fielder in history has accumulated as much WAR as Evans (67.2, according to Baseball Reference) and doesn’t have his own Hall of Fame plaque. So how can there not be another shot coming, one of these years, for one of the most beloved Red Sox players?

Lou Whitaker — Everything I just said about Evans applies to Whitaker. He appeared on this ballot six years ago and got six votes. That’s one more than Dave Parker, who has since been elected. But Whitaker hasn’t even made it onto another ballot.

Obviously, that Historical Overview Committee isn’t staring at the WAR leaderboard as long and hard as some people do these days. Whitaker’s 75.1 career wins above replacement are the most of any Hall-eligible infielder with no PED haze hovering over his candidacy. Whitaker’s longtime Tigers double-play partner in crime, Alan Trammell, got elected seven years ago. It’s strange that those two have never reunited in Cooperstown.

Others who missed this cut — Just so you understand the rules, a player needs to be retired for 16 years in order to qualify for this ballot. So put that outrage over Jim Edmonds, Lance Berkman, Johan Santana and Jorge Posada on hold, all right? Not eligible yet!

But all of these guys were:

Keith Hernandez

Bernie Williams

Kenny Lofton

Bret Saberhagen

David Cone

Kevin Brown

Mark McGwire

Sammy Sosa

Rafael Palmeiro

Will Clark

Orel Hershiser

Joe Carter

Nomar Garciaparra

Albert Belle

(And lots more.)

5. Will the new rules shape this vote?

Finally, there is one new wrinkle in this year’s election — and it’s about to have a massive impact on the players in these elections. It just might not be this year.

There used to be no limits on how often a candidate could show up on one of these era-committee ballots. Not anymore.

The magic number is now five. Starting with this election, any player who doesn’t clear at least five votes is officially on the hot seat. Here’s why:

• If he doesn’t collect at least five votes, the new rules would bar him from appearing on the next ballot of this committee in three years.

• He then would be eligible to make another appearance after that. But if he has a second election in which he drops below five votes, his time on these committees is over. He would no longer be a candidate for any future ballot.

So let’s think through a very plausible scenario on this year’s ballot. Let’s say the committee elects two players like Mattingly and Murphy. I have no idea if that’s where this goes, but it’s plausible, right?

Now let’s say Mattingly gets 15 votes, while Murphy gets 13. That would mean that nearly every one of the 16 voters had those two on their ballots — but they can only vote for a total of three.

There then would be only 20 combined slots left on the ballots of those 16 voters. What are the odds that, say, Bonds and Clemens both collect enough of the remaining votes to stay off the “Banned in 2029” list? That’s at least five apiece, remember.

If I were a mathematician, I could compute those odds. But since I’m not, I’ll just say: That seems hard.

And of course, it isn’t only those two who would be affected. It could be Sheffield and Kent. It could be Delgado and Valenzuela. It could be anyone on the ballot — because even Mattingly and Murphy have appeared on previous era-committee ballots and not gotten five votes.

So this rule will be on the mind of every future voter in every future era committee election. It will be a much bigger topic — with much bigger consequences — in the 2032 election. But now it’s one more thing to think about on Contemporary Era election night, which arrives in just four weeks.

Hopefully, I’ve prepared you for what’s coming. But who (if anyone) will emerge to ascend that stage in Cooperstown next summer? That’s not only the big mystery. It’s also the fun part.