You couldn’t help but laugh, watching it happen, though if you have a finely-tuned sense of empathy, perhaps it was a slightly sad laugh. The poor, poor Mets (the wrong word for them, admittedly, but it felt right in the moment) were doing everything they could. This weekend’s visitors to The Ueck were struggling even when they rolled into town, which so many of the Brewers’ recent opponents seem to have been—it always feels that way, when a team is as hot as this one is. After the taut game that Blake Perkins won with another magnificent throw to the plate Friday night, New York was downright spiraling.

Yet, their stars showed up over the first six-plus innings Saturday, giving them three home runs (one each from Pete Alonso, Starling Marte and Juan Soto) in the first five frames. (Alonso, Marte and Soto are making a combined $86.4 million this year, which is a bit less than the Brewers’ $114.4 million in projected spending for the entire roster—but that figure excludes $85 million in signing bonuses Steve Cohen paid to Soto and Alonso during the offseason.) They survived an early rally that was quintessentially Brewers, in which two runs scored on a bad-hop error after two singles and a six-pitch walk. They answered immediately after a game-tying Brice Turang home run. They led 4-3 at the stretch, with the game in the hands of their formidable, trade-reinforced bullpen.

The bottom of the seventh took a while, but in another sense, it went extremely fast. And when it was over, so (effectively) was the game. Milwaukee rushed up four runs, and the way they did it captures what makes this team not some cute, scrappy thing, but the inarguable best team in baseball this summer.

Ryne Stanek started the frame, and in theory, he had a relatively easy job. He was Edwin Díaz‘s chief lieutenant until the end of July, when ex-Brewers executive David Stearns rode the circuit and came back with trade prizes Gregory Soto, Tyler Rogers and Ryan Helsley. That group is awfully good, now, and Stanek suddenly being fourth on the depth chart for the corps meant he got to take on the bottom third of the Crew’s lineup in the seventh. Of course, the problem became immediately apparent: the Brewers’ depth is better even than that of the newly buttressed $340-million behemoth.

Turang, whose power binge is a delight worth savoring separately and whose defensive wizardry had saved one run already in the game, started the uprising with an at-bat more typical of his offensive skill set. On a fastball at 98.9 mph, he laced a line drive through the left side, for a single. Pat Murphy then sent up Caleb Durbin to pinch-hit for Anthony Seigler, which introduced a new threat (Seigler, though admirably serviceable with the glove all over and a good theoretical matchup piece, has not shown he can hit big-league pitching, whereas Durbin is hitting a torrid .296/.373/.417 since mid-May). Durbin hit another line drive, but this one found a glove on the infield. One out.

What makes Stanek good—not great, and it’s certainly best for the high-expectations Mets that they nudged him down the ladder a rung or two, but good—is how hard he throws. His slider and his splitter are his best pitches, in a sense, but they’re set up by the fact that he routinely hits 100 miles per hour. By the time he got to Joey Ortiz, he was stomping, snarling and sweating, and his heater was up in its highest gear. He threw a first-pitch strike to Ortiz at 99.4 mph, then got a foul ball on a late swing at 99.8. He came as close as you come to triple digits on an 0-2 pitch, having seen Ortiz struggle to keep up—but Ortiz, though still beaten, got enough of the ball to slice a lob-wedge double down the right-field line. It skipped out of play, which looked like a break for the Mets, since it stopped Turang at third. Now, though, the tying run was 90 feet away, with just one out. Turang, perhaps the face of the Brewers, also carried the speed that is so much part of their identity, so it’d be tough to get him if Sal Frelick could put the ball in play.

Normally, in the modern game, this is an anxious moment, but not an altogether hopeless one. The infield came in to the edge of the grass, but the Mets just needed a strikeout, and strikeouts are everywhere these days. Stanek has a 27.4% career strikeout rate. Manager Carlos Mendoza could have gone to Ryan Helsley right then, but he chose not to, and Stanek showed why. His first pitch to Frelick was just above the zone, rising and screaming at 100.5 mph, and Frelick swung under it. You could see the ambition in that swing. Frelick, who hasn’t tapped into his pop the same way Turang has this year but has certainly made strides, wanted to lash one of his signature ambush shots; he was just beaten. He took another healthy cut on 0-1, but Stanek’s heater was in nearly the same spot, at 101.0 mph. Frelick merely fouled it off.

Then the Brewers of it all took effect. Frelick visibly, tangibly changed his plan. Stanek went to the splitter to try to finish his much-needed punchout, but Frelick was punching now, too. He shortened his stride and his stroke, until he looked much like a kid hacking away at a piñata—but he fended off that splitter, and then another fastball at 100.3 mph. Stanek started to crack a bit, missing wide with the next heater, and then he came back with one more splitter. It was off the plate away, and Frelick’s swing was one of the ugliest things you’ll see this season—but he smacked the ball straight into the ground, sending a high-hopping grounder into the space just beyond Stanek and to the left of second base. Francisco Lindor picked it cleanly and retired Frelick, but Turang scored easily.

VndNVmFfWGw0TUFRPT1fQWdsU1ZBZFFYd0VBWEZJR1V3QUhBUVVDQUZnRVUxRUFBVk1BVTFBSENBSUVCUVZS.mp4

I say it’s one of the uglier things you’ll see all year, but it might not even have been the ugliest swing Frelick took against a two-strike splitter in this game. Earlier, in a similar situation but with two outs, he nearly earned an RBI infield single by doing… well, something, anyway… to a Frankie Montas splitter.

VndNVmFfWGw0TUFRPT1fVUFBREJsMEVYZ1lBRFZWVEF3QUhBbE1FQUFCV1cxZ0FVUWNBQkZGWFVsWUFVUUJU.mp4

Frelick’s bat speed on each of these little pokes was under 54 miles per hour. His answer to overwhelming speed was to push it away with a conscious absence of speed, and once each pitcher gave him their best offspeed alternative, he slowed down even more to find the ball—making him dangerous, even if slightly hideous.

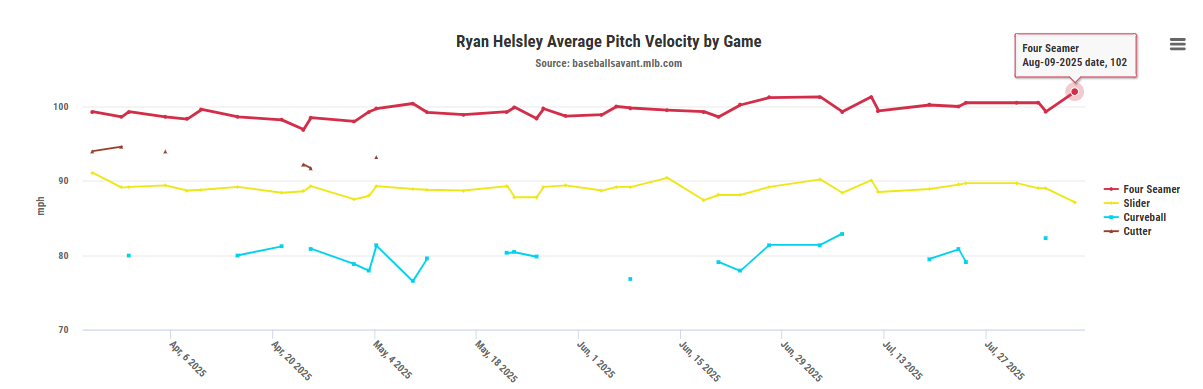

After that, Mendoza knew Stanek had given him all he could, and he called in Helsley to keep the game tied. Helsley always throws hard, but the combination of situation and occasion (the intensity of the game state and the fervor of the 40,156 in attendance) brought out a new level. For the first time in his career, Helsley averaged 102 mph with his heater.

Isaac Collins, though, was unimpressed. Like Frelick, he whiffed on the first pitch of his at-bat, at 101.1 mph. Like Frelick, though, he wouldn’t be beaten again. Helsley’s next three fastballs were something out of a 1990s baseball movie: 102.0, 102.8, 103.8, steadily growing angrier and more unimaginably unhittable—except that Collins fouled off all three. Helsley finally resorted to his slider, but missed. On 1-2, back he came at 103.1 mph, above the zone. Out Collins sent it, almost as fast but downward, toward third base. It went right by Ronny Mauricio at third base, a tricky hop on an utterly unreadable ball (who hits 103.1, neck-high, on the ground the other way?) and a carom into the outfield for a Brewers lead.

VndNVmFfWGw0TUFRPT1fVXdjQUFWY0FBd0VBQ1ZvSFVnQUhVRkpXQUZnR1ZGTUFBZ1pYQ0ZBRFVGZFZBVlJX.mp4

The Brewers will take your heart out. They will parry and foil everything you do well, looking defensive even on offense but using the space and their speed and the fundamental difficulty of this game to make your job so hard it becomes impossible. Then, when you’re bleeding and you make one small mistake, they’ll throw a haymaker you didn’t know they had left in their muscles. This time, the hammer fell when Helsley couldn’t quite get off his first pitch to William Contreras before the pitch timer expired. He still threw it, and Contreras hit a (looked-like) flyout to Soto in right field, but home plate umpire Ryan Additon stopped play while the ball was still in the air; Helsley started his stretch too late. Ball one. On the next pitch, Contreras got a heater just above the zone and just above 100 mph, but it was on the inner half, and he obliterated it, driving it into the Brewers bullpen for a two-run homer.

In that half-inning, alone, the Brewers saw 10 pitches at 100 mph or harder. We’re not talking, right now, about the two at 99.9 or the other two at 99.7. We’re also not counting the first pitch to Contreras, which officially doesn’t exist but was a 100-mph fastball. The Mets threw Milwaukee batters 10 counted pitches that were true, unmitigated triple-digit smokeballs—and the Brewers got their game-tying grounder, the go-ahead single, and the nail-in-coffin homer on them.

How do they handle such heat? Well, no team has to do it as often. In fact, no team comes close. After last night, the Brewers have now seen 117 pitches at 100 mph or harder this year. That’s the most in baseball, and it leads the second-place White Sox by 12. The Brewers have seen more triple-digit heaters than the Tigers (51), Red Sox (44) and Angels (26) combined. Athletics batters have only seen 17 pitches all season as hard as those 10 (or really 11) the Brewers saw in their four-run bottom of the seventh Saturday night.

It’s remarkable how much the Crew have had to deal with fastballs this fiery, because they throw so many of them, themselves. Only the A’s have thrown more triple-digit pitches than the Brewers’ combo of Jacob Misiorowski, Trevor Megill and Abner Uribe this year—and obviously, that was mostly Mason Miller. Milwaukee will end up throwing more pitches at 100+ than any other club this year, which makes the number of pitches their hitters have seen in that register mind-boggling. The reason the A’s (and Aroldis Chapman‘s Red Sox, for instance) see so few pitches that hard is that pitchers who throw that hard are still pretty rare. If you have one (or two, like Boston’s combination of Chapman and Jordan Hicks, or San Diego’s new tandem of Miller and Robert Suarez), you not only enjoy the benefit of their heat, but have removed a disproportionate part of the threat of having to face that heat elsewhere in the league. The Brewers are the only team with three of the top 20 pitchers in 100+ throws, but they’ve still been forced to confront more such pitches than anyone else.

And it doesn’t matter. Ugly as a Frelick lunge-chop or pretty as a Perkins peg, this team will find ways to win. Their triple-digit terrors are better at doing the other important things of pitching than yours are. Their defense is better at dealing with the occasional difficulties of working behind high-intensity hurlers than yours is. Their hitters are younger and quicker and smarter than yours, and they can do to your defense and your pitchers what you can’t do to them. The ball keeps moving, and the Brewers keep moving, and you try to keep up, but you end up looking like this:

Or like this:

Or like this:

One by one, opponents slide under the Brewers’ treads and come out the other side, flattened and furious, anti-congratulating themselves on playing so poorly and giving the Crew a game or a series. That’s the sign of a truly great team. The 2025 Brewers make everyone look like they’re beating themselves. Really, it’s the Brewers doing the beating. It’s all just happening too fast for anyone outside the Milwaukee Speed Machine to see.