If you’d gone looking for a distinctly Cubs-coded starting pitcher in the free-agent class two winters ago, you might well have come up with Shota Imanaga as tops on the list. He was a veteran starter with an elite walk rate and sneaky athleticism. Though not a strikeout artist, he showed the ability to limit not only walks, but hard contact. He didn’t throw hard, and he bordered on undersized, but Imanaga was well-rounded and smart—and left-handed. Jed Hoyer, above all, loves a southpaw.

With Imanaga and Justin Steele already in the rotation, one might have reasonably expected that the team would want to diversify last offseason. Instead, though, they locked in on Matthew Boyd—another lefty, without high-end velocity, whose specialties were avoiding walks and working his way to weak contact. Under Hoyer, the Cubs adore a lefty starter who lacks velocity but not command; who needs to work in front of a good defense; and who can therefore be had for middle-tier prices despite having a high-end track record.

Every time they acquire another such pitcher, though, it gets a bit harder to justify. As well as the strategy has been working (as far as it goes), the approach has effects that ripple out to the entire roster. Because the Cubs are unwilling to pay what it costs to land pitchers who miss bats at the best rates in the league (and, perhaps, reluctant to accept the extra walks and/or home runs that come when you shop for that skill, instead of command and pitchability), they have to remain extremely stout defensively. That comes with tradeoffs when building a winning offense. It also tends to mean lifting starters earlier, which forces the team to amass more relief depth.

Hardest of all to work around, perhaps, is the fact that pitchers who can do what the Cubs want pitchers to do tend to have acquired those skills gradually, rather than being born with them. Hurlers with low walk rates and low opponent hard-hit rates tend to be experienced, and therefore expensive. There are few pitchers who meet Hoyer’s standards and are still in their team-controlled seasons—let alone still having minor-league options. Building pitching staffs in the Hoyer style pulls money away from run production in the name of run prevention, even if not all of that money is spent on pitching itself—and it erodes roster flexibility, too.

On the other hand: Hoyer’s genuinely good at finding guys who will thrive in the system he’s built. The Cubs have a good coaching and development infrastructure on the pitching side, even if the things they do don’t work as well with draftees and young prospects as with free agents or waiver claims. There’s something to be said for knowing what they’re good at and staying committed to it.

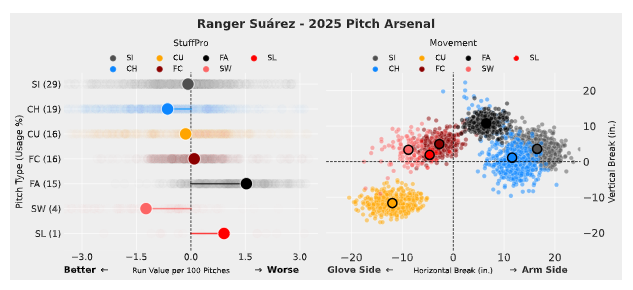

In that light, it’s time to talk about Ranger Suárez. This week, the Phillies southpaw will decline his former team’s qualifying offer. If Imanaga turns down the Cubs’, too, there will be an opening near the top of the Chicago rotation, and no pitcher in the free-agent pool fits the Hoyer prototype quite like Suárez does. He struck out 23.2% of opposing batters in 2025, which is about as high as his punchout penchant rises. He fanned just over 25% of hitters in 2021, but that was as a swingman, and it came back when he threw 93-94. Now, he’s more like 90-91.

Suárez does have exceptional control, though. He walked just 5.8% of opponents last year, the lowest rate of his career. He fills up the zone with a deep mix, the best offering within which is a changeup that can induce both whiffs and grounders.

Because hitters can never lock in on one pitch (and because his sinker has such good arm-side run), Suárez excels at inducing weak contact. He keeps the ball in the park well, and batters had just an 85.7-MPH average exit velocity against him in 2025, considerably lower than the league average.

Suárez turned 30 in August, and he’s in line for a four- or five-year deal. He’ll make upwards of $20 million per year, and signing him would come with the added cost of a lost draft pick and forfeited spending power in international free agency next year.

Then again, all the alternatives to Suárez also come with extra costs. In addition to fellow qualifying offer recipients Dylan Cease, Zac Gallen, Michael King, and Framber Valdez, there’s Imanaga, but if he turns down the QO, the Cubs would lose their chance to reclaim a draft pick if he signs elsewhere. There’s also Tatsuya Imai, who would only cost cash, but it looks like he’ll cost much more cash than Suárez—not only because he’s younger, but because whatever he signs for will come with a 15% posting fee paid to the Seibu Lions.

Can the Cubs stomach one more pitcher just like the best ones they already have? You can make a fairly strong case against it, but Hoyer spent the GM Meetings in Las Vegas making the case for it, instead.

“I think we’ll see where the right value is. See who are the guys that that we’ve, you know, ultimately, the guys you usually sign are the guys you value more than the industry. And think that’s kind of the nature of the game, right?” Hoyer said. “Like, Matt Boyd last year, was very clear, like, that was a guy we wanted to sign. We may have valued him higher than the industry, but that’s okay. And you know, I think those are the guys you end up signing in free agency, those are the guys that I’m trading for, is the guy you probably value a bit higher than other people.”

That doesn’t automatically mean the Cubs will be in on Suárez, or that they’ll sign him, but sources familiar with the team’s thinking predicted they will at least show interest. Unless his price tag runs much higher than expected, Suárez will be one of the Cubs’ top targets this winter. Is that a good thing? The answer depends on how wise you think their approach to run prevention has been over the last few years.