None of the newcomers on the Hall of Fame writers’ ballot got the sendoff they deserved. All 12 of the first-time candidates played their final games in 2020, in empty ballparks during the pandemic. The fans returned the next season, but these players did not.

None of them reached 3,000 hits or struck out 3,000 batters, like Ichiro Suzuki and CC Sabathia, who debuted on the ballot last year and quickly cleared the 75 percent threshold for election.

If any of the newcomers get to Cooperstown, it could take a while. Carlos Beltrán and Andruw Jones, holdovers who both cleared 66 percent last winter, are more likely to hear their names called on January 20, when the Hall announces the results.

However long they stay on the ballot, the new dozen can always say that they made enough of an impact to be considered for baseball’s highest honor. In that spirit, here is our annual tribute to each of them.

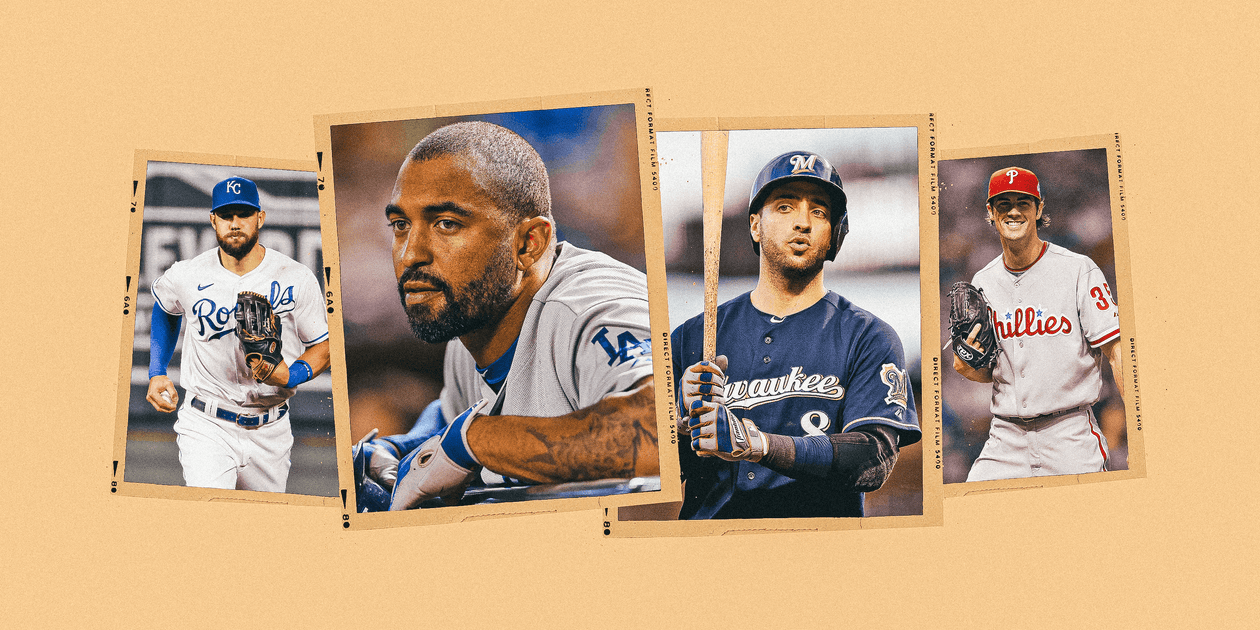

Ryan Braun

Braun cost himself a chance at the Hall of Fame with a series of poor decisions in 2011 and 2012. But what if he had never been caught cheating? He would have a fascinating case.

On the field, Braun was Dick Allen, who finally earned a plaque, posthumously, last summer. Both were Rookie of the Year third basemen who later won an MVP at a different position. Both were frequent All-Stars who reached the NLCS but never the World Series.

They are separated by 17 games and 25 plate appearances. Braun had 352 homers, one more than Allen, and hit .296, four points better than Allen. Their slugging percentages were almost identical, but Allen walked more and had a better OPS, .912 to .891.

One big difference was that Allen played for five teams while Braun spent his entire career with the Milwaukee Brewers. He was the Robin Yount of his generation.

An unbroken bond between a player and team can elevate a candidacy. Would Todd Helton and Edgar Martínez, for example, have plaques if they had bounced around? Maybe, but their status as loyal stalwarts of hard-luck franchises probably helped, at least a little.

Braun would have been a similar case, given everything he means to the Brewers. But he saved us all the hassle.

Shin-Soo Choo

Choo is by far the most accomplished MLB hitter to come from South Korea. He spent 16 seasons, mostly with Cleveland and Texas, as an on-base machine with extra-base power, and learned his trade at an all-baseball high school.

As Choo described it, the player-students practiced for five hours every morning, starting at 7. After an hour break, they practiced more. At 5 o’clock, they broke for showers and dinner, then lifted weights from 9 to 10 p.m. They slept on campus and visited their families on Sundays.

Choo thrived and earned a $1.35 million bonus from the Seattle Mariners. But he said it left students with no career options besides baseball and a warped perspective on the sport.

“These guys make bad plays, bad games, they can forget about it, today’s a new day,” Choo said in 2010, referring to his MLB teammates. “But when I first got here, I was used to the Korean style. I had a bad game last night and still care about it the next day. Now I feel better. I feel more American style now.”

Speaking of style, Choo eventually adapted to the preferred helmet of major leaguers, going with a single earflap for most of his time with the Rangers. For years, though, he was pretty much the only non-switch-hitter to wear the head-hugging, two-flap helmet. He won’t be elected, but wouldn’t you love to see that on a plaque?

Choo wears the double flap helmet in this 2011 game while playing for Cleveland. (Peter G. Aiken / USA TODAY Sports)

Edwin Encarnación

For most of his 424 career home runs, Encarnación rounded the bases as if ready to throw a punch. Starting with a grand slam in 2012, his distinctive trotting style involved holding his right arm aloft and parallel to the ground, like a branch for an imaginary parrot.

Many T-shirts, GIFs, stuffed animals and #WalkTheParrot hashtags helped make the Encarnación trot a one-of-a-kind classic, a physical catchphrase like Fernando Rodney’s bow-and-arrow save celebration or Ozzie Smith’s pregame backflip.

The man himself still loves it — he struck the pose at the World Series when the Rogers Centre scoreboard showed him cheering on the Blue Jays — and he did it quite often in the 2010s. Only one hitter, Nelson Cruz, bashed more home runs in that decade than Encarnación, who had 335.

Gio González

Imagine marrying your childhood sweetheart when you’re living in a nursing home. That was González and the Chicago White Sox. It was destiny, long-delayed but inevitable.

In the early years, they kept getting together and breaking up. Someone else would always come along. They bonded when González was 17 years old, a first-round pick from a Florida high school in 2004. The next December, the Philadelphia Phillies offered a brawny strongman, Jim Thome, in a trade. So long, Gio.

A year after that, the Phillies wanted a veteran pitcher, Freddy Garcia, so the White Sox obliged and reunited with their old flame. But 13 months later, a charismatic slugger named Nick Swisher caught their fancy, so off went González to Oakland. He still had not pitched in the majors.

And then he did, for a dozen years. He was an All-Star with the A’s and the Washington Nationals. He started in the NLCS for the Brewers. He earned 130 victories and made lots of money.

At last, when González was 34, the White Sox signed him as a free agent. González didn’t have much left, but he pitched 12 times, struck out his final hitter and never pitched another game. It was meant to be.

Alex Gordon

Should he have gone for it? Would you? Two outs, bottom of the ninth, down by a run, Game 7 of the 2014 World Series. Your team probably won’t get another hit off the ace of all October aces. Maybe your best chance is to keep on running.

“Oh, absolutely,” Gordon said six years later, before a morning practice at his final spring training with the Kansas City Royals, when I asked if he wished he had run through the stop sign.

“Even if I would have ended the game on a close play like that or a replay, or if I would have run over Buster Posey at home plate, who knows what would have happened? It would have been a crazy way to end it, either win or lose.”

The Royals lost to the San Francisco Giants when Madison Bumgarner got Salvador Perez to pop out, stranding Gordon at third, where he pulled up after a single and two-base error in the outfield. He agreed with third base coach Mike Jirschele at the time: “He made a good call holding me up,” Gordon said after Game 7.

The feeling here is that Brandon Crawford would have easily nailed Gordon at the plate. In any case, Gordon took care of things himself in his next World Series game, against the New York Mets one year later.

Down by a run again in the bottom of the ninth, Gordon smashed a game-tying homer off a quick pitch by Jeurys Familia. It was the only ball the Royals hit over the fence that entire World Series (they also had an inside-the-park homer). They won the opener in 12 innings, took the series in five games, and Perez was the MVP.

Gordon played his entire career with the Royals. So has Perez, who just signed another contract extension. History rarely works out so neatly, with instant redemption for the ideal leading men. But in Kansas City, it did.

Cole Hamels

The summer after his sophomore year at Rancho Bernardo High School in San Diego, Hamels ran into a parked car while playing touch football. He tried to pitch that night and fractured his humerus bone. Doctors inserted two rods, and Hamels missed his junior year.

Hamels had never thrown very hard, but had learned a changeup because he needed something to fool hitters. It earned him a spot on the varsity and became his lifeline as his arm healed.

“For that whole year, I still kind of knew that would be the easiest pitch, because it’s not a lot of stress on the area,” Hamels recalled for my book, “K: A History of Baseball in Ten Pitches.”

“You’re not trying to muscle and engage and jack everything around. So mentally, I was like: at least I know I can always throw this pitch.”

Hamels grew stronger as he recovered, improving his fastball and making his changeup even more effective. It soon would help him compile the fourth-most pitching WAR in Phillies history, after Hall of Famers Steve Carlton, Robin Roberts and Grover Cleveland Alexander.

All of them pitched in the World Series, but only Hamels was the MVP, in 2008 against the Tampa Bay Rays. And if you ever want to understand the thought process behind his signature pitch, there’s no better explanation than this:

“It’s like you dead-arm it,” Hamels said. “That’s what I try to tell people: fastballs are strong, changeups are dead. So if you can grasp that concept of how to control and deaden something in your body, then you’re able to get the basic idea.”

Matt Kemp

The Los Angeles Dodgers took Kemp in the sixth round of the draft in 2003. Earlier in that round, the Royals took a pitcher named Ryan Braun. It would not be the first time that a “Ryan Braun” was dubiously chosen ahead of Matt Kemp.

Braun the pitcher did not last long in the majors. Braun the hitter beat out Kemp for the National League MVP award in 2011. Kemp had a better OPS+ than Braun, with more hits, homers, runs batted in, steals, runs scored and total bases. But Braun’s Brewers made the playoffs, and the Dodgers did not. Braun won easily.

When Braun accepted a PED suspension two years later, stemming from a positive test in that MVP season, Kemp said he believed Braun should be stripped of the award. That’s not how it works, and Braun kept the plaque.

Kemp’s season, though, turned out to be more of an outlier than Braun’s. After collecting an NL-best 8.0 bWAR and 40 stolen bases in 2011, Kemp amassed 4.6 bWAR and 40 stolen bases, total, across his final nine years.

In a way, though, Kemp continues to help the Dodgers. The second time they traded him, to the Cincinnati Reds in December 2018, they received a three-player package that included a promising infielder named Jeter Downs. A year or so later, they would trade Downs to the Boston Red Sox as part of a deal for Mookie Betts.

Howie Kendrick

In 2019, with the Washington Nationals, Kendrick had the best part-time season in the history of baseball. That’s a big claim, I guess, but how could anyone else compare?

Kendrick was 36 years old and up for anything. He started 70 games and came off the bench for another 51. He logged a lot of time at first, second and third. When he started, he was great (.330). When he pinch-hit, he was even better (.361).

Overall, Kendrick batted .344 with a .966 OPS in 370 plate appearances — outstanding, but it was only his opening act. In the NLDS, Kendrick broke a tie in the decisive fifth game with a 10th-inning grand slam at Dodger Stadium. In the NLCS, a sweep over St. Louis, he hit .333 to win MVP.

And then, in Houston for the seventh game of the World Series, Kendrick hit a home run that will reverberate forever in Washington. Protecting a one-run lead in the seventh inning, Houston’s Will Harris dotted the outside corner with his best pitch, a cutter. But Kendrick drilled it off the screen attached to the right field foul pole for a two-run, lead-flipping homer.

A smudge from the yellow pole is still visible on the ball. You can see it in Cooperstown.

Nick Markakis

When Markakis played for the Atlanta Braves, his manager, Brian Snitker, captured him perfectly. Markakis, Snitker said with admiration, was a “consummate, boring pro.” That was in 2018, the only All-Star season of a remarkably steady career that lulled you in a good way, like a nap in an easy chair after an honest day’s work.

Markakis rarely missed a game or a pitch to hit. He collected 1,651 hits in the 2010s, more than any other player except Robinson Canó, who had artificial help. They are similar to the duo atop the 1990s hits leaderboard: Mark Grace and Rafael Palmeiro. (Markakis is the Grace in that analogy, Palmeiro the Canó.)

Usually, it is tough to finish first or second in hits in a numerical decade without getting to Cooperstown. Of the 20 players to do it in the last century, 14 are enshrined. The exceptions include Canó and Palmeiro (steroids), Pete Rose (gambling) and Bob Elliott, an MVP from the 1940s who did not serve in World War II.

That leaves Grace and Markakis. The outgoing Grace had the more memorable career, with a higher average and OPS than Markakis’ .288 and .781. But Markakis was similar: a lefty hitter with multiple Gold Gloves, no batting titles, no seasons with 200 hits or 25 home runs — and an intense dislike of strikeouts.

“It drives me nuts when people say strikeouts don’t matter,” Markakis once said. “If you’re striking out 150, 200 times a year, that’s 150, 200 times you’re up at the dish and absolutely gave yourself and your team zero chance.”

Daniel Murphy

On April 1, 1985, Sports Illustrated broke the story of a French horn player who practiced yoga in Tibet and flung 168-mph fastballs in spring training for the New York Mets. “The Curious Case of Sidd Finch” caused quite a stir — until people noticed the cover date on the magazine.

That same day, in Jacksonville, Fla., Daniel Thomas Murphy entered the world. Thirty years later, as the Mets’ second baseman, he lived out a tale nearly as tall as the famous Finch hoax. Across a half-dozen magical October games, Murphy hit a home run every night.

Nobody else has ever had a six-game postseason home run streak. And Murphy did it off some of the game’s best pitchers: Clayton Kershaw, Zack Greinke, Jon Lester, Jake Arrieta, Kyle Hendricks and Fernando Rodney.

“Science fiction,” said an awestruck Ron Darling in the TBS booth. “It’s not really happening. It can’t be.”

By the end of the spree, the Mets had won their first pennant in 15 years. But Murphy slumped in the World Series, with three singles in 20 at-bats against Kansas City. Never a slick fielder, he made a pivotal error in Game 4 to help push the Mets to the brink of elimination.

The World Series seemed to confirm the Mets’ suspicions that Murphy’s hot streak was a fluke, and they let him leave for the rival Nationals as a free agent. With Washington, though, Murphy was better than ever, hitting .329 with a .930 OPS. In each of his first two seasons, he made the All-Star team, won a Silver Slugger award and helped the Nats unseat the Mets as NL East champions.

The April Fool’s Day baby was no joke.

Hunter Pence

Pence was not your typical four-time All-Star and two-time World Series champion. In so many ways, he was one of baseball’s most endearing characters.

“I’m twitchy,” Pence said, on a podcast with Julian Edelman. “Everything’s unorthodox.”

Pence had wild eyes, a scraggly beard and basically wore shorts on the field. When he tried wearing his pants below the knee, he explained, the elastic cuffs squeezed too tightly on his scratched-up shins. So he rolled them above the knee and felt faster.

One year, for his Players’ Weekend jersey, Pence used “Underpants” on the back because it kind of sounds like “Hunter Pence.” He rode a scooter to the ballpark for playoff games in San Francisco and took the strangest on-deck circle swings you’ve ever seen.

Famously, in Game 7 of the 2012 NLCS, a pitch shattered Pence’s Louisville Slugger, then somehow touched the bat three times, imparting a dizzying spin that eluded the fielders and cleared the bases. He talked about it with Conan O’Brien.

The Giants won the World Series that year and did it again in 2014, when Pence hit safely in every game and batted .444. And just when he looked finished, he signed a minor-league deal with his hometown Texas Rangers in 2019 and earned one last All-Star nod.

A certified caffeine junkie, Pence and his wife, Lexi, are now co-owners of a coffee shop/gaming hangout in Houston called Coral Sword. He has also become passionate about environmental advocacy, with a nonprofit called Healthy Planet Project.

“The Earth is going to be just fine,” Pence told the San Francisco Examiner last year. “But if we don’t restore it, if we don’t preserve it, humankind won’t survive. I just want to do my part to pass on a beautiful earth to the future generations.”

Rick Porcello

It might be a startling commentary on the state of modern pitching, but here goes: they just don’t make ’em like Porcello anymore.

In 2009, at 20 years old, Porcello reached the majors and started 31 times for the Detroit Tigers. For the next decade, with the Tigers and Red Sox, he would always make between 27 and 33 starts with enough innings to qualify for the ERA title. He would now be considered an iron man.

Porcello was a mid-rotation anchor for good teams and got halfway to 300 victories despite a 4.40 career ERA. Only three others have 150 wins and an ERA that high – Willis Hudlin from the live-ball 1930s, and steroid-era righties Liván Hernández and Tim Wakefield.

At various points, Porcello led his league in hits allowed, home runs allowed, hit batters and losses. But it all came together in 2016, for Boston, when he was 22-4 with a 3.15 ERA and led the majors in strikeout-to-walk ratio.

Porcello’s old Tigers teammate, Justin Verlander, got more first-place votes for the Cy Young Award — but Porcello won, beginning a four-year stretch in which he made 131 starts and threw 792 innings. That might seem unremarkable, historically, but it’s not anymore: in the last four seasons, not a single AL pitcher can match those totals.