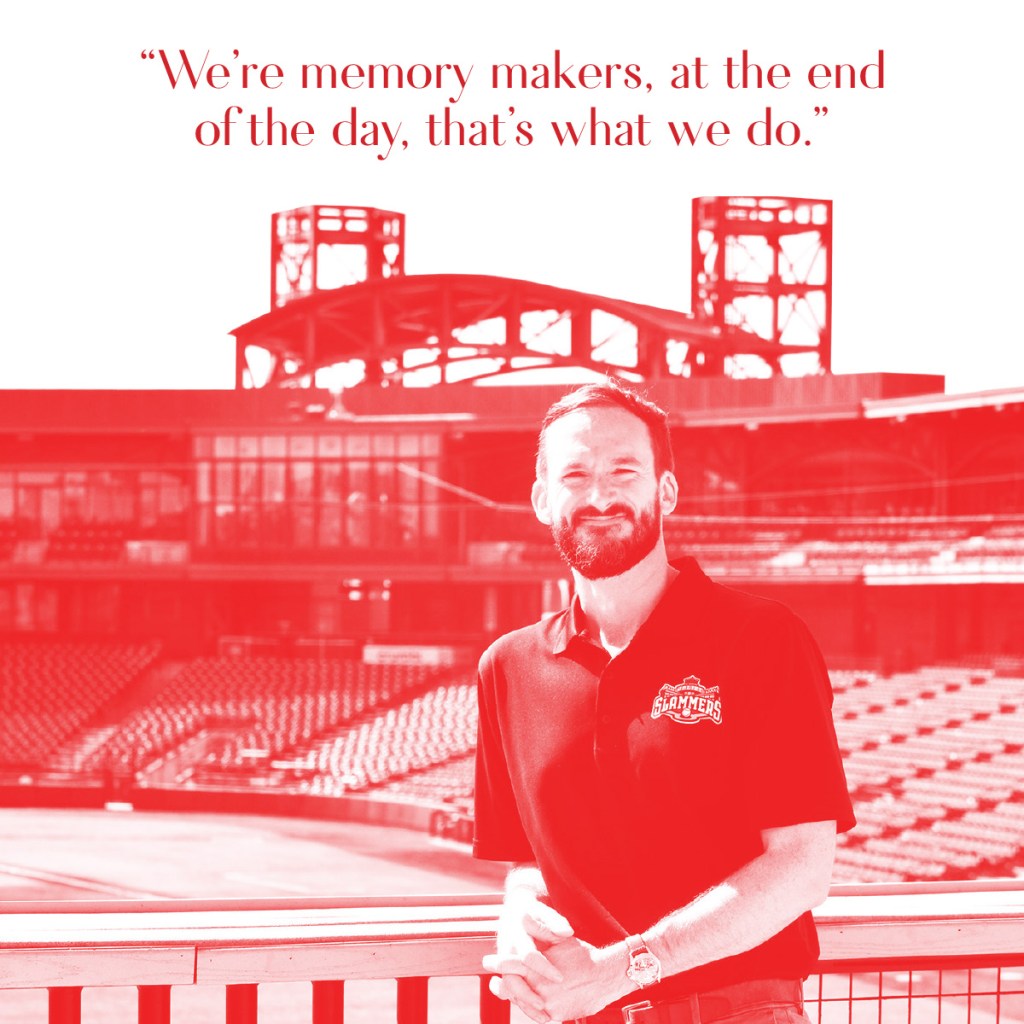

South Loop resident William Night Train Veeck traces his career in professional sports back to the age of five, when he’d help vendors selling sodas and hot dogs to Saint Paul Saints fans. Night Train grew up in a baseball business dynasty. His great-grandfather, William Sr., served as the Chicago Cubs’ president from 1919 to 1933. His grandfather, William “Wild Bill” Jr., owned the Chicago White Sox on two separate occasions—including during the infamous 1979 “Disco Demolition” promotion, which was cohosted by his son Mike, who happens to be Night Train’s father. After nearly a decade away from baseball, Mike relaunched his baseball career in the minors as team president of the Miracle in 1990—during his tenure, the team moved from Miami to Fort Myers, Florida. Night Train was a little kid when his dad returned to baseball, and he got to experience the inner workings of the pros before joining the business side full-time with the minor league RiverDogs in Charleston, South Carolina. He’s since worked for the White Sox and Australia’s Big Bash cricket league, and he helped launch the Chicago House soccer team in 2020. In 2024, Night Train, his father, and Bill Murray acquired a majority stake in Joliet’s minor league baseball team, the Slammers. Night Train works as the team’s executive vice president of sales and marketing, where he spearheaded an attempt to break the world record for most hot dogs dropped from a helicopter in an hour. (They missed the record by 24 dogs.)

I’ve been in baseball and sports marketing my entire life. I don’t know if we’re still in the tradition phase—it might actually be baked in at this point—but [I’m] fourth generation in the business. I think I started breaking a couple child labor laws at about five years old, and fell in love with it. Born in Florida, and moved all around with my family, ping-ponging back and forth with different teams.

[I’m named after Richard] “Night Train” Lane, who used to play for the Detroit Lions. Great guy off the field, and he’s a Hall of Fame defensive back. I guess my dad didn’t want me to get picked last for any baseball teams, so you could say it worked. It’s made for an interesting ride; it made middle school a little weird, but past that, it’s something that people can’t forget. So, I’m glad for that part. My dad, I think he underestimated the amount of paperwork that would need to occur with a name like Night Train.

I started out in concessions. I was on the grounds crew for a time; I was in game day staff, promotions, marketing, ticket sales, box office—anything in a ballpark, you name it, I was doing it. I realized, “This is fun.” I got to just be so immersed in it that I really don’t know that I can identify the exact moment, but I know that when I was able to walk out of a stadium, or look into a stadium and see it full, and see people having fun, and being happy . . . I mean, we’re memory makers, at the end of the day, that’s what we do. Being able to create those for people is the best.

Credit: Kirk Williamson

Credit: Kirk Williamson

After dressing up like a slice of pizza, or a palm tree, or in a wedding dress [for] a fake proposal, I transitioned over to the ticket sales side in Charleston. That was my first job out of college. Did a little bit of everything—it’s minor league baseball, so you wear a lot of hats. I was there for two years, and then started with the White Sox shortly after that.

Walking in there for the first time—because the last one of us to walk out of there was fired by his dad for blowing up some disco records—it meant a lot. It was really special. It allowed me to come back, contribute to an organization that I always had a special feeling for, and bring something of my own to the table. I had some fun conversations. Shout out to Chef Roy [Rivas], who had been there for I think 40 years; he fed three generations of my family; [head groundskeeper] Roger Bossard was another one.

My dad, he loved it. He was always, “Open this box up with your own eyes and at your own risk.” It’s definitely a really cool path, but there’s a lot of work. It’s long nights and long days at the stadium. I think he wanted to make sure it’s what I really wanted. I worked for him for a time, and he really enjoyed that.

A friend of mine sent me a job description, and it was a lot of what I do—it was marketing, creating fan experiences, and a little bit of partnerships. I know just about every baseball team in the country, and when I saw “Melbourne” on there, I was thinking, like, “Melbourne, Florida?” It was Melbourne, Australia—that part wasn’t on there. The Big Bash League there was in its sixth year of existence at that point, and it was outdrawing Major League Baseball by about six hundred fans a game. It’s what I would call the youngest, most successful sporting league in the world. They were revitalizing the game of cricket that was experiencing a lot of the same things that Major League Baseball was. I wanted to go work at the league level, and then go work around a league that was starting to do some of the same things that minor league baseball was, and approach it in a different way, to get the next generation of fans. I didn’t know anything about cricket, I didn’t know anything about Australia—and there we were. It was a wonderful experience, and it gave me a few things to bring back to the American side.

Some people just want to come out and have a good time, and that’s what I want to bring more of.

We had a couple of options and offers to stick around there, and it was a really great experience, and I love that part of the world. My sister was sick—I wanted to come back and be with her, and the rest of my family, and help take care of her. So, came back and started up an independent soccer team, during COVID—which was a whole story in itself. I’ve never been happier to see three thousand fans show up to a game on night one, after starting a team in your living room, back-to-back with your partner in an apartment in Chicago.

About two years ago, [we] started looking at a few teams. My dad had actually been looking a little bit before that, and thought, “This might be an interesting one.” He and I had always wanted to work together again. January 1st of last year I hit the ground running with the Slammers. The last year and a half have gone by in a blink.

Credit: Kirk Williamson

Credit: Kirk Williamson

Joliet, it’s a great town. It ticks the boxes. The personality, the spirit, the people here, the growth that’s happening—even in just the downtown Joliet area, the projects that are going on—it’s great. This is a town that really cares about their team. It’s also a town that doesn’t look at you too funny when you say you want to drop 2,600 hot dogs out of a helicopter.

I saw this very unceremonious picture of a guy in Detroit dropping these raw hot dogs out of a helicopter, and I just thought, “This is hilarious.” I asked a couple of people around, “What would you think if we did something like this?” Full credit to my staff here, they were great. They came back and had all these other ideas to put it into action. One-hundred thirty-six degrees, that’s what you need a hot dog to be safely served at—and kept at temperature while it’s in the stadium and awaiting to go to the helipad. It was just over three-and-a-half minutes from the helipad to the stadium. [Federal Aviation Administration] and the city shut down some city blocks. It was a really big production and undertaking, and we pulled it off.

[I like] bringing more of that entertainment piece to the team. It’s always a welcome addition, and I think fans crave that—especially nowadays. Prices are going up, and you see that across the board, so keeping things affordable—young families being able to come out, not break the bank, and have a fun time. That’s the best. We have some fans, ten percent of them will come out with a score book, every single game, and keep perfect score—they have for years. But not everybody loves the game like that. Some people just want to come out and have a good time, and that’s what I want to bring more of, and continue to bring into the future.

This was originally published in the 2025 edition of our People Issue, the Reader‘s annual celebration of everyday Chicagoans doing extraordinary things through their own words.

More in NEWS & CITY LIFE

The news you should know in the city you love.

The Justice-Championing Pastor

November 19, 2025

The tenth People Issue represents the resiliency and joy of Chicagoans.

November 19, 2025

The Replicator

November 19, 2025

The Movement Architect

November 19, 2025

The tattoo evangelist

November 19, 2025

The Musical Fabulist

November 19, 2025