After a third-place finish in National League Rookie of the Year balloting in 2024, Jackson Chourio had a slightly less impressive sophomore campaign. Plagued by some erratic swing decisions and a hamstring strain that cost him a month of playing time, Chourio still demonstrated a strong blend of power, speed and defensive ability, but his on-base percentage fell to .308. He put the ball in the air more often, but the majority of those extra fly balls went to the opposite field. The encore to Chourio’s brilliant rookie showing yielded the sustained promise one might have hoped to see, but also some more difficult adjustments than expected.

In one regard, though, Chourio did take the developmental step fans had hoped for. He became, by one measurement, the best hitter in the league against offspeed stuff. In fact, after being a total of 4 runs better than average on changeups and splitters in 2024, he was a whopping 14 runs to the good in 2025. In 2024, he batted .241, slugged .448 and whiffed on 34.2% of his swings against offspeed pitches. This season, he batted .431, slugged .810, and whiffed on just 27.6% of those swings.

The change came because Chourio changed his timing a bit. Although his aggressive approach (his swing rate rose from 48.8% to 53.4%) would imply that he started earlier and would catch the ball farther in front of himself, in fact, he made contact about 1 inch deeper in the hitting zone against offspeed pitches and 2 inches deeper against breaking balls. That was with, as Statcast measures it, the same average bat speed on each pitch type in each season.

You can see the way he effected that change by looking at what he did against fastballs. On heaters, his contact point remained constant, but his average swing speed spiked from 73.0 miles per hour to 74.3. Statcast reports swing speed at the moment when a player’s swing intercepts the pitch (or, on a whiff, when they would have done so had they connected). Thus, although bat speed (the concept, as scouts evaluate it and players must train it) isn’t inherently tied to timing, the stat you see if you visit Baseball Savant is. If a batter is making contact at the same point (relative to his body) while swinging substantially faster when they make contact, they started their swing a bit later. You can make the same inference if a hitter is swinging at the same speeds against given pitch categories but making contact deeper in the hitting zone, as is true of Chourio and offspeed or breaking stuff.

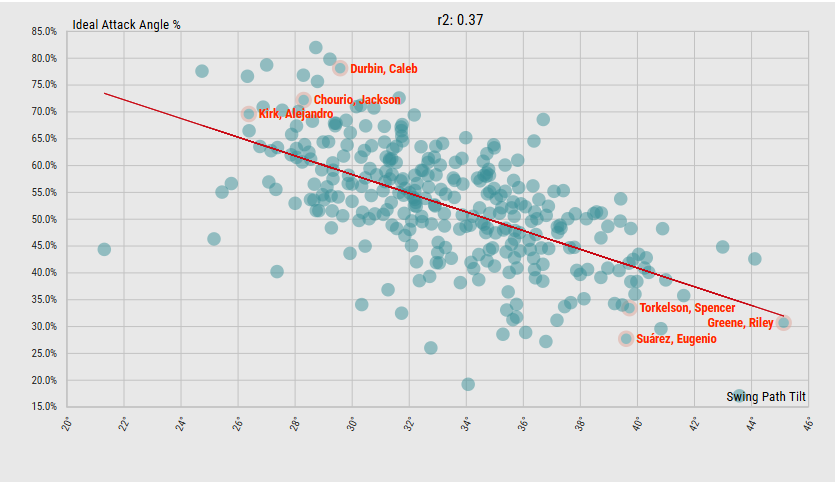

That explains why Chourio was better in 2025 than in 2024, and on its own, it’s a good thing to keep in mind. However, we also want to know why Chourio’s ceiling against offspeed offerings is being the best hitter in baseball on them. To start that process, consider this chart:

This plots a batter’s average swing tilt (the angle between the bat’s orientation at a specified point early in the swing and a hypothetical horizontal line running through the handle) against the percentage of swings against offspeed pitches on which the hitter’s swing falls into what Statcast calls the Ideal Attack Angle range, from 8° to 20°. For those who are unfamiliar with attack angle, it’s the angle at which the barrel of the bat is traveling at the intercept point on a swing, relative to the ground. As you can see, there’s a strong, negative correlation between the input and the output. Against offspeed stuff, a flatter swing yields a greater likelihood of encountering the ball in the window where a swing is likely to generate squared-up, lofted contact.

I’ve highlighted a few players at each end of the spectrum, to give you a sense of what each thing looks like. Guys who work steeply uphill on offspeed pitches tend not to catch them in the ideal window often, because hitters are more likely to be early on those pitches, and a hitter who already has steep swing tilt and is early on a pitch will end up with far too high an attack angle by the time the ball gets to them. Flat swings give a hitter more margin for error, because (relative to steep swings) the batter’s attack direction (the angle of the barrel relative to an imaginary line from the mound to the plate at the intercept point) is changing faster than their attack angle as the bat passes through the hitting zone. Being fooled by an offspeed pitch produces a bigger change in attack direction (and a smaller one in attack angle) for a guy with a flat swing than for a guy with a steep one.

Of course, it would be a leap in logic to assume that clustering around the ideal attack-angle zone automatically means producing more real value. In fact, it would technically be an erroneous one. Search for an individual-level correlation between attack angle, attack direction or swing tilt and production (here, we’re using Statcast’s Batter Run Value per 100 pitches as the proxy for production), and you won’t find one—but that’s because you’d be looking at the wrong thing.

There are too many variables involved in producing value (even when we confine that definition to production against a specific pitch category) for swing tilt to shine through as a determining factor, for reasons we’ll come back to shortly. For now, let’s look at some data visually again—this time, in a table.

Swing Tilt Range

Fastballs

Breaking Balls

Offspeed

25° or Less

-2.818

-2.026

-2.961

25-28°

-2.31

-1.763

-2.711

28-31°

-2.233

-1.746

-3.428

31-34°

-1.634

-1.904

-2.852

34-37°

-1.789

-1.244

-2.862

37° or More

-1.547

-2.23

-3.201

That’s the run value per 100 pitches (on swings only) for the whole league, broken down by pitch category and swing tilt. Yes, all the values are negative; taking a pitch is usually the better bet. All we need to focus on, though, is the relationship between the values. Notice that, for breaking balls and fastballs, the sweet spot for swing tilt is at the steeper end of the band. In fact, when it comes to heaters, the steeper, the better. That’s almost true of breaking balls, too. Not so with offspeed pitches, though. The best value on those is in the 25-28° range.

You don’t want a slightly flat swing against offspeed pitches, but you don’t want a very steep one, either. The best swings on those pitches are very flat or medium-steep. That’s a compelling finding, but it’s hard to parse.

We can make it more manageable, as it turns out, by breaking things down by handedness and platoon split. Let’s make a simple flat-versus-steep binary, just for convenience’s sake. That way, we can focus on the variables of pitch category and platoon dynamic.

Pitch Types

RHH v RHP

RHH v LHP

Four-Seamers

Whiff Rate

RV/100

Whiff Rate

RV/100

Steep

20.2

-1.813

17.2

-1.045

Flat

24.2

-2.415

23.3

-2.505

Sinkers/Cutters

Steep

15.1

-2.173

16.2

-1.81

Flat

15.4

-2.448

16.6

-2.23

Breaking

Steep

32.7

-1.788

30.6

-1.893

Flat

27.8

-1.878

22.7

-1.907

Offspeed

Steep

35.9

-2.948

35.5

-3.165

Flat

26.9

-1.422

28.4

-3.132

Pitch Types

LHH v RHP

LHH v LHP

Four-Seamers

Whiff Rate

RV/100

Whiff Rate

RV/100

Steep

17.6

-1.396

20.8

-1.071

Flat

22.5

-2.874

22.6

-1.548

Sinkers/Cutters

Steep

15.6

-1.202

17.7

-2.82

Flat

16.5

-1.845

15.8

-3.246

Breaking

Steep

30.1

-1.553

33.8

-3.246

Flat

21

-0.957

30.2

-3.186

Offspeed

Steep

32.1

-2.983

36.1

-2.693

Flat

25.4

-3.603

28.2

-4.851

This is a dense presentation of data, but I can break it down for you pretty quickly: regardless of batter handedness or platoon advantage, steeper swings do better on fastballs. That’s a deeply counterintuitive finding, for most people, because fastballs come in flatter—but remember, we’re not measuring the attack angle, here. A flatter attack angle is good and necessary against fastballs, but that stat captures timing. Swing tilt is a question of mechanics—of bat path—and steeper actual swings are more productive on heaters.

Against breaking balls, righty batters with steep swings will whiff more, but they make up for that with better results on swings where they make contact; swing tilt doesn’t make a big difference for righties hitting breaking balls. For lefty hitters, however, it does—at least against right-handed pitchers. In those settings, flat swings are better. Against southpaws, left-handed batters struggled mightily against breaking balls, pretty much regardless of swing tilt.

Now, we come to offspeed stuff. Against those pitch types from left-handed pitchers, righty batters have the same dynamic as against breaking stuff from either handedness of pitcher. Steep swingers whiff much more, but basically make up that value on their other swings. Against righties’ offspeed offerings, though, look at the glaring gap between flat and steep swingers. The righty hitter with a flat stroke is much, much better against same-handed offspeed offerings than is the one with a steep swing. Lefty batters, by contrast, do much better on offspeed stuff if they employ a steep swing, regardless of which hand the pitcher throws with (and despite whiffing more than their flat-swinging counterparts).

Let’s tackle that dynamic a bit more completely, by breaking things down in one more way. Here’s the run value per 100 swings for both lefties and righties, on pitches on which they’re either far around the ball (with an attack direction oriented at least 10° to their pull field) or not yet square to it when they hit it (with an attack direction of at least 10° toward the opposite field). I’ve also broken those swings down into three outcome categories, to illuminate how that value is generated.

Attack Direction

Heavy Pull

In Play %

Foul %

Whiff %

RV/100 (All Swings)

RHH

26.1

35.5

38.4

-1.984

12.953

LHH

23

39.4

37.6

-2.572

12.95

Heavy Opposite

In Play %

Foul %

Whiff %

RV/100 (All Swings)

RHH

30

44.4

25.7

-2.625

6.051

LHH

29.6

44.3

26.1

-3.151

4.651

The simplest way to frame this is: lefty batters depend more on being on time to generate value than do righties. When righties mistime it and either hit the ball the other way or pull it at steep horizontal angles, they do better than do lefties. Thus, a righty batter with a flat swing but a dangerous overall skill set is in really good shape to hit well against offspeed pitches.

This has a direct application to Chourio, of course, but I learned a great deal about the nature of swings and their interactions with pitch type and platoons in the process. As our understanding of swing data evolves, we’ll keep unearthing many unexpected insights into the complexities thereof. Today’s is that steeper swings work against fastballs, and flatter ones can do damage against softer stuff—as long as you’re a right-handed batter. That’s how Chourio became excellent against offspeed pitches in 2025, but it’s also why he might need to tweak his swing and generate a bit more tilt in it for 2026.