Although his new colleague has caught more headlines early this season, Miguel Amaya has been phenomenal at the plate. Carson Kelly is still slowly coming down from his extraordinarily hot start, but even as he does, Amaya is emerging as the backstop with the higher long-term offensive upside. Last season, we saw a glimpse of this, as he tapped into a vein of exceptional contact skills during the second half.

In early July, with his career dangling in front of him by a thread, Amaya agreed to eliminate his leg kick and adopt a minimalist lower-half swing mechanic. For the balance of the campaign, he hit .282/.331/.468. In 173 plate appearances, he had 16 extra-base hits and only struck out 20 times. His plate discipline wobbled, and he went off the rails a bit in the final month of his first full major-league season, but Amaya demonstrated a real and valuable offensive adaptability.

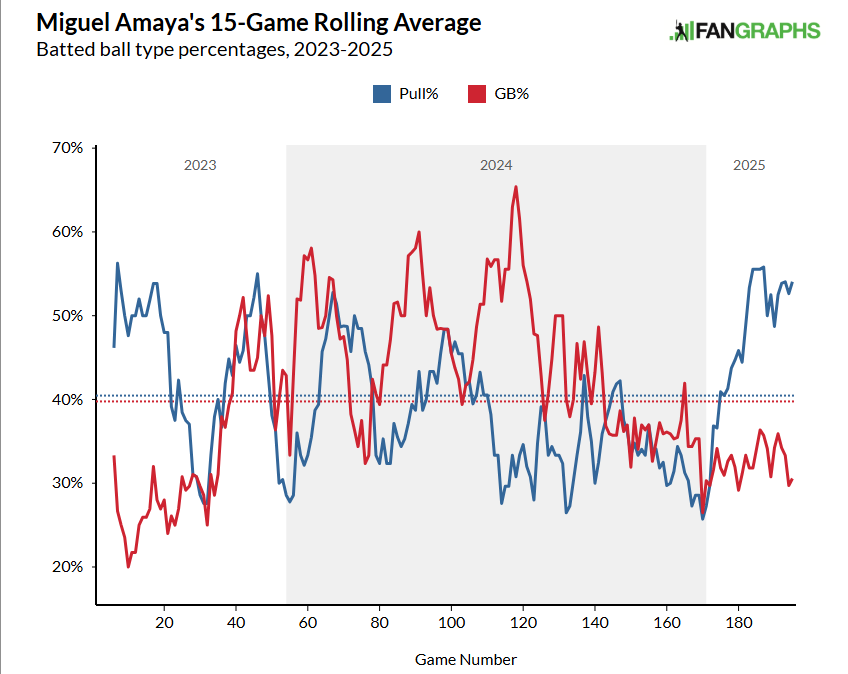

There was a minor problem, though. Amaya’s new setup and lower-half move didn’t necessarily fit his fast (but flat) swing path. He came up as one of the Cubs’ best hitters in terms of raw bat speed, but without much loft in the swing. The result was a lot of relatively low-value batted balls, with inefficient contact resulting in some of that swing speed being wasted. He didn’t find the launch-angle sweet spot very often, with a few too many pop-ups in 2023 and too many grounders in 2024. Nor was he pulling the ball as much as you want a player with above-average bat speed to do so. Ditching the leg kick gave him the opportunity to be earlier, but in practice, he just started later. He started elevating the ball better late last year, but he didn’t start pulling it consistently.

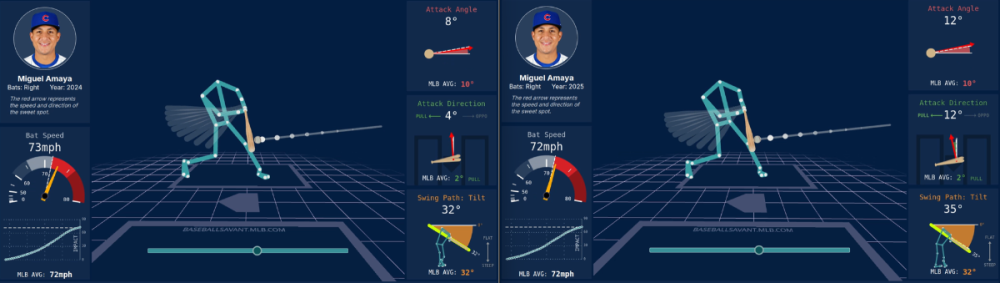

As you can see, that’s changed this year. In fact, it’s radically different. Amaya is now a dead-pull hitter, and he’s also hitting the ball on the ground less often than he has since the very start of his career, two full years ago. That’s how he’s managed to generate a .287/.323/.529 line over his first 94 plate appearances of this season, despite not hitting the ball as hard as he did last year; striking out more than he did last year; and walking very rarely. The fascinating thing, though, is how he transformed that batted-ball profile, physically. Thanks to Statcast’s new swing path, attack angle and attack direction metrics, we have a newly expanded ability to visualize hitters’ swings and quantify their movements. In Amaya’s case, this is especially revealing.

Let’s start with the headlines: One of the new numbers rolled out at Baseball Savant this week (Swing Path Tilt) can be thought of as the swing-change number. If a hitter has altered how they’re hitting the ball, they might have changed their swing, or they might merely have changed their timing and their approach. To see which, check their swing tilt. If it’s unchanged, the hitter hasn’t really changed their swing. Swing path tilt gives the degrees by which a hitter’s bat angles downward from an imaginary line running through the handle of the bat, parallel to the ground. The league’s average tilt is 32°. Very flat swings sit in the mid- to high 20s, while very steep swings get to around 45°. Obviously, how much hitters tilt their swings varies based on which pitches they’re swinging at (low pitches require more tilt; high ones demand a flat pass), but this one number can tell you whether the bat is moving materially differently than it has in the past.

Amaya’s has certainly changed.

So, we’re looking at an inarguably steeper swing, but importantly, this change didn’t take hold as soon as Amaya made his stride change last summer. In August and September, his swing path tilt was just 31°, so he didn’t steepen his swing when he altered the movement of his lower half.

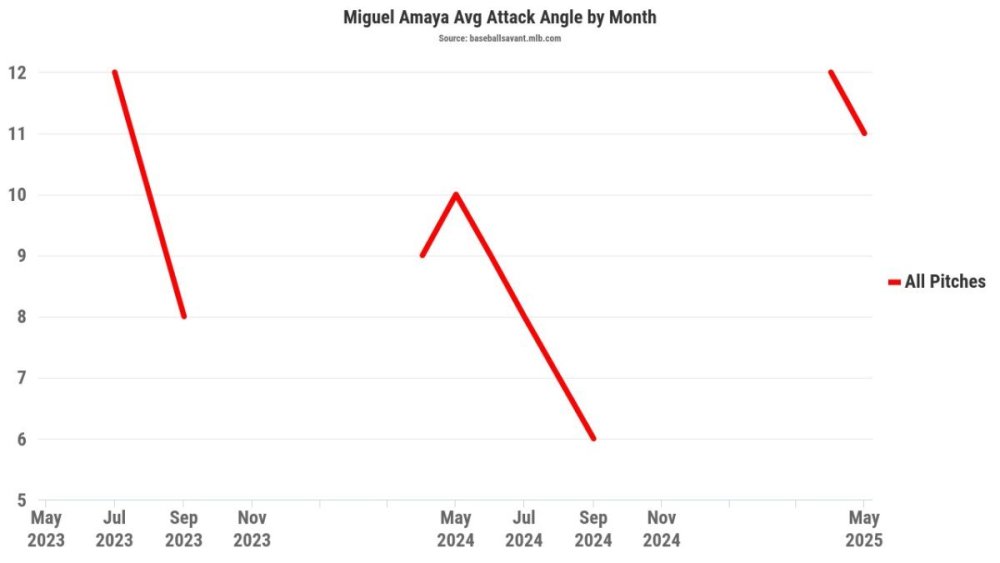

We can also study his Attack Angle, which gives the vertical angle of movement of the barrel of the bat at the contact point. A steep swing will beget a steep attack angle, of course, although they aren’t perfectly correlated. Attack angle tells us not how the hitter orients their bat, but how they address the ball within the hitting zone. It is, in some ways, a timing metric, because the attack angle will change fairly dramatically throughout a swing, so if a hitter meets the ball just a bit farther in front of their body, the angle might be much higher—whereas if they start to catch it deeper, the attack angle will shrink toward 0°.

Last summer, when Amaya changed his stance and stride, he only saw his attack angle go down.

That’s not necessarily bad news. Remember, he did strike out very rarely in the second half of last year, thanks to a huge boost in contact rate. Swings with flatter attack angles tend to be the ones you hear about as “long through the zone”, with room for error on timing. You might mistime a swing with a flat attack angle, but instead of whiffing, merely mishit the ball. Still, it’s noteworthy that the attack angles have jumped for him this year. We’ll get back to that.

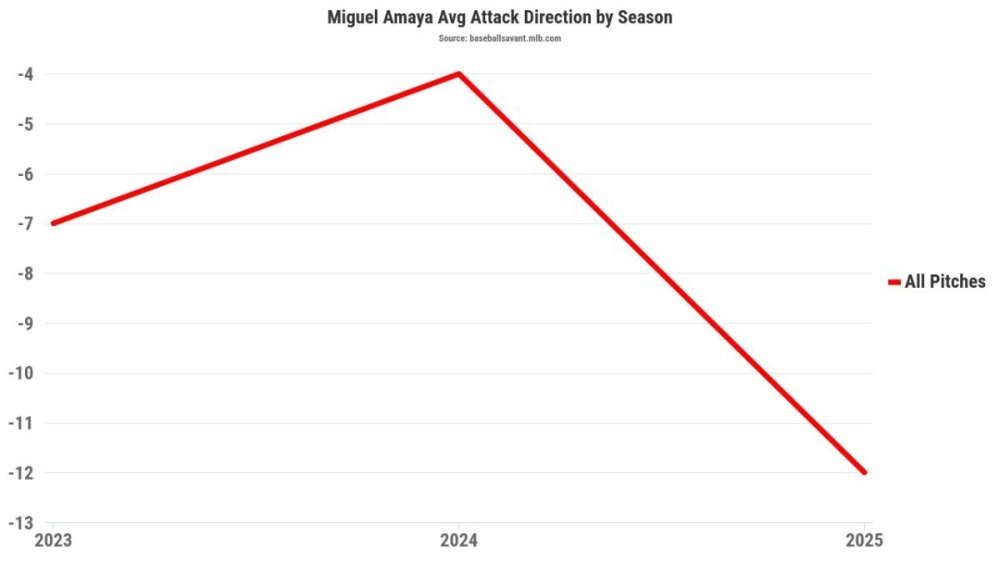

Finally, there’s attack direction—the horizontal angle of travel of the barrel at the contact point. In other words, has your bat yet passed the point where it’s perpendicular to the incoming pitch, or not, and by how much? This is expressed in degrees, too, to either the pull side (if the bat has already passed that point of being perfectly square to the ball) or the opposite field.

Amaya had, on average, met the ball slightly on the pull side, through the end of last year. This spring, there’s nothing slight about that tendency. This isn’t surprising, of course; we saw the spik in his pull rate, far above. Still, it’s telling by how much the attack direction of the bat itself has changed.

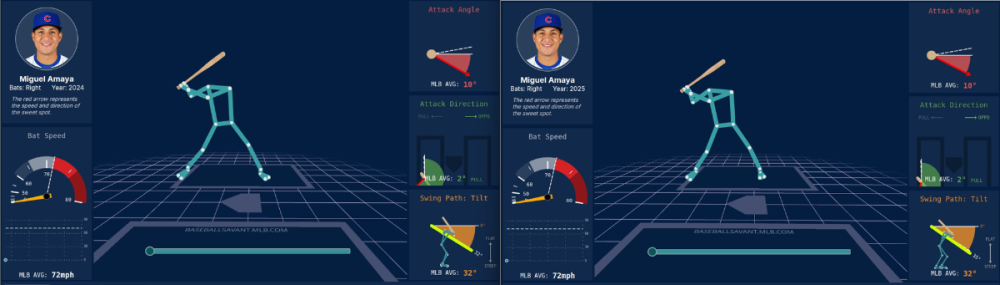

Let’s talk about how he’s moving in more detail, though. Statcast also furnished new visualizations this week, allowing us to see a hitter’s swing from beginning (more or less, the moment their front foot lands in its final position) to end. That can help us see how, exactly, a hitter’s swing path tilt, attack angle or attack direction might have changed. Here’s what Amaya looked like in 2024 (left) and what he looks like in 2025, at the start of his swing.

There’s already a couple of slight differences here. Can you spot them? As you’d guess, for a player who has quieted his stride, we see that Amaya is more upright and less spread-out this year. He’s got more weight left on his back side, and his front hip and foot haven’t opened up as much as they did right away last year.

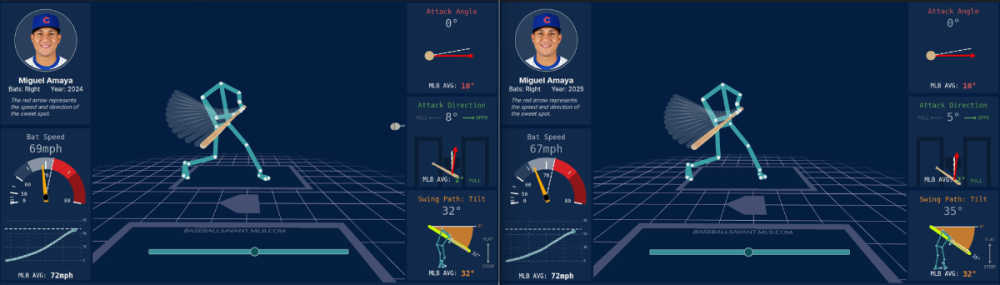

Now, here’s the moment in each season when his attack angle gets to 0°. Every swing has to start downward, of course, so it’s good to check when a hitter’s bat stops that angled descent and begins to get “on plane,” as hitting people put it, with the pitch—and what their body looks like at that instant.

We’re starting to see the steepening of Amaya’s swing come into play, here. Note that this year, his bat is not up to the same speed by the time he gets to attack angle 0. Indeed, his overall swing speed is down this year. Yet, he’s closer to attack direction 0 already—and, crucially, look at the right side of each snapshot. The animated ball has entered the frame for 2024 Amaya. By the time he got on plane, last year, the ball was almost on top of him. This year, he’s still working with some time. The steeper swing means that his arms aren’t yet as extended and his bat isn’t as fast, but he’s going to be on plane better by the time the ball arrives, because he’s started bringing the bat onto that plane earlier in the flight of the pitch.

Now, here he is at contact, both last year and this year.

Even at contact, Amaya’s arms aren’t as extended this year. In theory, that means less power—or at least, less exit velocity. We have seen that. Since his bat has been working uphill just a bit longer and is just a bit more past its point of flatness to the incoming pitch horizontally, though, he’s pulling it more often—and specifically, pulling it in the air, much more often. His season-by-season Pulled Air%, according to Statcast, tells the story.

2023: 24.7% of batted balls in the air to the pull field

2024: 13.1%

2025: 30.9%

As a pitcher must think about what happens if they miss their spot, too, hitters have to think about what happens if their timing is wrong. With his old swing, if Amaya was late, he was likely to hit a ground ball up the middle or to the right side. With his new one, that’s almost impossible. A late Amaya will still line it up the middle or push the ball the other way. Here’s the percentage of all his batted balls that have been grounders up the middle or to the opposite field, for each year of his career.

2023: 20.5%

2024: 24.1%

2025: 13.3%

Meanwhile, if last year’s Amaya was early, he’d have a chance to hit a hard line drive or fly ball—but it would probably be to center or left-center. He’d also be more likely to roll over and hit a grounder, because hey, look again at that contact point snapshot above: last year, he was closer to full extension and to rolling his wrists than he is at contact this season. This year, an early Amaya is more likely to loft the ball to left field, and while that can generate a few lazy fly balls, it can also generate this.

MnJPazVfWGw0TUFRPT1fQVFaV1ZsVUhYZ29BQVFGUVVnQUhBMVZSQUZoUlVRSUFBVkpRQWdFRkJ3QUdBMWNB.mp4

Amaya has hit a bunch of balls better than that this year. He’ll hit a bunch more. But if you build a steep, still-fast swing with a pull orientation and you’re a bit early, you have a chance to occasionally mishit a home run. Last year, Amaya wasn’t going to mishit a ball out of the park.

Kelly’s production has been a godsend to the Cubs. Amaya still has plenty to work on, including and especially plate discipline. After last year’s change to his lower-half mechanics, though, we’re seeing a true swing change in 2025, and it’s turned Amaya into a much more dangerous hitter.

.thumb.jpeg.3c56061ce48a04ad46a865192d42b546.jpeg)