PHOENIX — Atlanta Braves prospect Nacho Alvarez Jr. chased a slider outside of the strike zone, and it chased him from the lineup for two weeks.

As Alvarez reached out with his swing, he felt a sharp pain in his side.

“My left side just blew up,” Alvarez said.

Infielder Alvarez, 22, was sent to the injured list with a strained oblique, an injury that is becoming more common among hitters with each passing year.

An Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine study looked at abdominal injuries that hitters in Major and Minor League Baseball sustained from 2011 to 2021 and found that the number of oblique injuries grew steadily over the decade-long span. The study also found that oblique strains were the third-highest time-loss injury in baseball over that stretch, only trailing hamstring and rotator cuff strains.

In 2011, there were 61 oblique injuries sustained by hitters across MLB and MiLB. In 2021, that number skyrocketed to 112.

“The main abdominal muscles that people tweak, especially when they’re doing high rotational activities, like swinging a bat or throwing a baseball, are your intercostals,” said Zachary Tenner, Mount Sinai Hospital physician and co-author of the study. “So the muscles are like right between your ribs, and then your oblique injuries, the oblique muscle sits on top of the intercostal.”

The rise in oblique injuries has raised questions as to why this is happening. There could be a variety of factors, but there is one main culprit.

Bat speed.

Similar to how there is a correlation between the rise in velocity and a rise in pitchers’ arm injuries, the increase in oblique injuries could be linked to the rise in emphasis on hitters’ bat speed. Pitching velocity has been tracked consistently in MLB since 2008, while bat speed has only been made public since 2023. But that doesn’t mean that bat speed was never tracked prior to 2023.

In 2014, a company called “Blast Motion” released the first bat sensor that tracked a hitter’s swing speed, swing path and time to contact. Today, teams and training facilities use various companies such as Rapsodo, HitTrax and others to measure everything about a player’s swing.

Driveline Baseball, a training facility with locations in Scottsdale, Seattle and Tampa, works with baseball players of all levels. Professionals flock to it during the offseason because it is analytically driven, coupled with the resources it provides to athletes.

“The fact that we have a motion capture lab here and all our facilities that can actually track the bat through space, that kind of technology becoming more prevalent has obviously made it a lot easier because it’s really hard to train something if you can’t objectively measure it,” Driveline Baseball hitting trainer Eric Kozak said.

With so much information readily available, numerous hitters are spending their offseasons trying to gain an extra mile per hour or two of bat speed to increase their power. The constant chase to swing harder can also put the player at risk of injury.

Boston Red Sox first baseman Triston Casas tore the cartilage between his rib cage and sternum after a swing early in the 2024 season. Casas told The Athletic when he was put on the injured list, “(The doctor) pretty much chalked it up to me being so big, rotating so fast, so many times that I created a car crash within my body. It was a matter of time before this happened. He said it was something similar to like a pitcher needing Tommy John, just an inevitable thing that was going to happen sooner or later.”

As sports medicine and science continue to evolve, athletes are becoming bigger, faster and stronger. Although athletes are reaching new heights, it’s important to remember the body’s limitations.

“The athlete has changed, the training techniques have changed, the knowledge around everything has changed,” Arizona Diamondbacks catcher James McCann said. “For the better, right? As far as the product that we’re receiving on the field, you got guys throwing harder than ever, you got guys hitting balls harder than ever.

“But I think that with all that, and the evolution of bat speed, I think the human body is still the human body. I think that at times we’ve reached the max potential of what the human body can handle. When you start reaching that threshold, something is going to go and then leads to different types of injuries like the oblique injuries.”

A hitter’s bat speed can be impacted by where they make contact with the ball. Hitting philosophies have changed over time, and in today’s game, hitters try to make contact more out front so they can pull the ball in the air, allowing them to hit for more power.

The further out front a hitter makes contact with the ball, the faster the bat speed will be.

“When someone’s pulling the baseball like that, that’s just a general higher rotational velocity that they’re providing that they put on the ball as compared to somebody going the opposite way,” Tenner said. “So if you’re looking at somebody like Joey Gallo versus Luis Arráez (both free agents), Joey Gallo is predisposed to getting this kind of injury because he’s rotating at such a higher rate versus someone else that’s trying to slap a ball the other way.”

Gallo is a former slugger who was notorious for selling out for power, trying to hit fly balls to the pull-side. By doing so, Gallo always had very low batting averages and struck out more than most, but he was still a dangerous hitter because he could hit a home run at any moment. His bat speed in his last season in 2024 was 72.4 mph. A versatile outfielder/infielder, Gallo recently announced his intention to convert from a position player to a pitcher.

Arráez is the complete opposite. He lets the ball get deep and peppers soft line drives to the opposite field for singles. He rarely strikes out and never hits for any power, leading to three-straight batting titles along the way. His bat speed in 2025 was 62.6 mph, the slowest in baseball.

They are two very different hitters, but both yield similar overall offensive results. On-base plus slugging percentage, better known as OPS, is a very common statistic that measures a player’s overall offensive output. Gallo’s career OPS is .775 and Arráez’s is .777.

So if players like Gallo and Arráez can have two completely different bat speeds with similar offensive outputs, why do hitters risk injury by trying to increase their bat speed?

Arráez is an exception, not the rule. He gets away with it because he has elite bat-to-ball skills that are unbelievably difficult to replicate. In the 2025 season, Arráez made contact with 94.7% of the pitches he swung at. The league average is 75%.

“There are no qualified hitters this year on Baseball Savant that swing under 62.6 (miles per hour) on average,” Kozak said. “Luis Arráez, Steven Kwan and Jacob Wilson are the three slowest swings and they’re 62.6 to 63.9 on average bat speed. But those guys are also crazy elite bat-to-ball guys that, for most humans, is not a realistically attainable skill to match them.

“If you swing 58 miles an hour, there is no comparable big leaguer because nobody with that low of bat speed has made it to major leagues, much less been successful, so it probably behooves you to get inside of the range where there are good hitters, particularly where there are a lot of good hitters. Trying to chase the outlier is rarely a recipe for success and just having all that information so available makes people understand its value but also dedicate their training economy accordingly.”

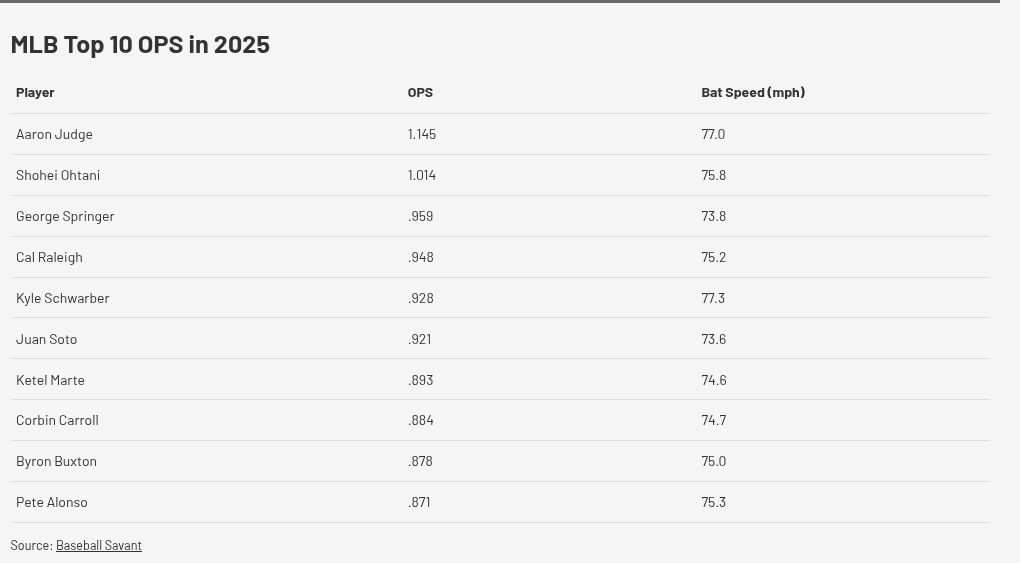

With the exception of the very few players similar to Arráez, there is a relationship between higher bat speed and better results.

In 2025, the MLB-average bat speed was 71.8 mph. Baseball Savant classifies a “Fast Swing” as a swing that is 75 mph or faster.

MLB hitters hit .313 with a .631 slugging percentage with fast swings last season while swings below 75 mph yielded a .250 batting average and .380 slugging percentage. Fast swings also produced a 54.7% hard-hit rate whereas the slower swings had a 37.2% hard-hit rate.

Meanwhile on the bottom of the list, only four of the 10 worst OPSs in baseball had league-average or better bat speed. New York Yankees shortstop Anthony Volpe’s 72.6 mph bat speed was the highest of the bottom-10 OPS list.

“The easiest way to put it is that it really sets both your floor and ceiling as a hitter,” Kozak said. “If you swing faster, that means that every ball you hit is going to be hit harder. You have more potential energy at your disposal to transfer to the baseball.

“It’s about the margin for error that peak (bat speed) affords you as a hitter. It’s really hard, especially at higher level baseball, like professional and big leagues. Pitchers are really good. Their stuff is nasty. It’s really hard to consistently be on time and hit pitches well. For the luxury of an increase in margin for error where you can miss a ball and still be productive is pretty crucial.”

An important statistic? Look at the drastic difference in Lee’s production when his bat speed is above and below 69 mph. That’s an entirely different ballplayer. Even for a contact-first hitter, bat speed matters, and Jung Hoo Lee must train to swing fast. pic.twitter.com/dBcmwvOgU7

— Matthew Knauer (@matthewk36711) November 11, 2025

Kozak characterizes it as a cost-benefit and risk-reward evaluation for each player. With today’s technology, teams and coaches can project what a hitter’s production could be if they lost or gained a certain amount of bat speed. These projections can help players guide their decisions as to how much they need to focus on bat speed training in the offseason.

“We can say like, ‘Hey, if you can gain two miles an hour bat speed this off season, it’s probably going to be worth $4 million a year versus like if you don’t you’re going to make what you made this year and if you lose bat speed you’re going to make $5 million less or you won’t be in the big leagues anymore,’” Kozak said.

It is no surprise that oblique injuries can be linked to bat speed, because the abdominal muscles are pivotal for generating power in a swing. More specifically, the lead-side oblique of the hitter is the main source of generating power among the abdominal muscles. Lead-side oblique injuries accounted for 71.4% of all hitter’s oblique injuries from 2011 to 2021, according to the study.

The lead-side is the side of the oblique that is opposite from the player’s dominant side. A right-handed hitter’s lead side oblique is his left oblique, and a left-handed hitter’s lead side is his right oblique.

Hitters are always going to be at a higher risk of injury when they are swinging at max effort, which is why proper training techniques are important to limit that risk. Training for higher bat speed, like most physical improvements, begins in the weight room.

“It starts in the weight room with single segmented, single-sided rotational activity with force and also a combination of mobility, making sure that our (thoracic) spine and our torso rotates the way it should, so then those muscles aren’t notoriously tight,” Arizona State associate athletic trainer Jesse Lowman said.

Russian twists, cable rotations and side planks are just a few examples of abdominal exercises baseball players typically use to build core strength. A strong and explosive core often results in explosive swing speeds.

In the batting cages, there are a variety of ways to increase bat speed. On top of that, no two hitters are the same. Every player has a different swing and body that will react differently to the same teachings. That is why it’s imperative to find drills that will work for each specific player.

The most common and “old-school” drill is using a heavy bat. A professional baseball player typically uses a bat during a game that weighs between 29 and 34 ounces. In the cages when they are trying to add bat speed, they may use a heavy bat that weighs over 40 ounces. Heavy training bats come in a variety of sizes that can reach up to 60 ounces.

Another drill hitters can do is called “stick-ems,” where hitters take a normal swing but stop their bats at where the point of contact would be. By stopping the swing as quickly as possible, the drill activates hitters’ core muscles and makes them stronger.

Sometimes, the problem can be mechanical.

“The idea is you really want to identify what is the low-hanging fruit in terms of creating an adaptation and increasing bat speed,” Kozak said. “You’ll see a guy who’s extremely powerful and strong and produces a ton of force but their swing mechanics are really lacking and inefficient sequencing, poor movement patterns where a lot of the bat speed is gained.

“It’s not that they can’t produce a bunch of force when they swing, it’s that they’re not producing it correctly, they’re not transferring energy efficiently up the chain. They’re basically just relying on their arms to swing. That guy needs a large dose of mechanical work to improve his kinematics and transfer energy more efficiently because he already has a ton of force output, but he can’t transfer it out to the barrel.”

When in the batting cages, Kozak believes the most important thing is swinging with intent. A hitter swinging with intent means they are swinging the bat as hard as they can with control, in hopes of hitting for power. By training with intent, it makes the hitter’s obliques build a tolerance for more violent swings in the game.

At Driveline Baseball, instructors tend to work with hitters six days a week. Kozak said that three of those days are considered “bat speed days.” Those are the days that the primary focus is to increase bat speed and not worry as much about contact.

One of the drills that Driveline Baseball does on those days is called a bat speed derby, in which the players compete with themselves by swinging as fast as possible with every swing. Kozak said another benefit from the bat speed derbies is that it accelerates the motor learning process of the hitters due to the immediate feedback and the ability to make rapid adjustments.

With numerous exercises and drills to increase bat speed, it is vital that players and coaches closely monitor workload.

“You can just do so much that you put the obliques in this fatigued state, and then you try to go swing a bat to try to catch up to the 95 mile an hour fastball and you have a chance of hurting it,” Lowman said. “We have guys that want to go in and take 1,000 swings a day after practice, and that’s an exaggeration, but we have to tell our hitters, ‘You swung enough today, do not go. You will not swing any more today.’

“Because again, you keep swinging a bat, eventually there’s muscle fatigue and you’re at risk for injury.”

If a player does hurt his oblique, returning to the field is a tedious process.

The most efficient way to rehab a strained oblique is to rest as much as possible. It can be a long process because the oblique muscles are so large and strong to begin with, meaning that when obliques are hurt, the injury is usually significant.

“Because they are a core muscle, and a muscle that helps keep us upright, moves us even reaching for a cup in the cupboard, we’ll just never get the chance to shut them off,” Lowman said.

“A hamstring strain, I could technically put them on crutches and really give the hamstring a break for a few days to start the healing process. The oblique doesn’t get that because every time you breathe, the oblique works, every time you take a step, the oblique works. So obliques are hard to rehab just on that premise alone.”

Lowman said once the player is able to get up in the morning and do everyday activities without issue, then the rehab process begins with simple range-of-motion and body weight exercises. From there, normal baseball activities and weight training begins once the player no longer feels pain.

The severity of the strain and a player’s pain tolerance generally dictates recovery time. Depending on those factors, Lowman said he has seen oblique injuries keep players down for 10 days, but he has also seen some sidelined for up to seven months.

Injuries are the worst things about sports. They obviously are not good for the players, as it causes pain and can cost them accolades and future earnings. But it’s also not good for fans who want to see the game played with the best players possible, and that level of competition reduces when players are unable to suit up for games.

Team training staffs and players do all they can to limit the injury risk, but sometimes injuries are unavoidable.

The conversations surrounding how pitcher’s arm injuries can be attributed to pitchers throwing as hard as possible has been thoroughly exhausting, and now the same questions are being raised about hitters hurting their obliques by swinging as hard as they can.

Hitters are forced to decide whether chasing bat speed is worth the injury risk for their career. It’s an unfortunate reality, but the benefits of higher bat speeds are undeniable. So hitters almost have no choice.

“To hit people that are throwing so hard nowadays,” Alvarez said, “You have to swing hard.”

This <a target=”_blank” href=”https://cronkitenews.azpbs.org/2025/11/24/mlb-injuries-oblique-trend-basebal/”>article</a> first appeared on <a target=”_blank” href=”https://cronkitenews.azpbs.org”>Cronkite News</a> and is republished here under a <a target=”_blank” href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/”>Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License</a>.

<img id=”republication-tracker-tool-source” src=”https://cronkitenews.azpbs.org/?republication-pixel=true&post=98323″ style=”width:1px;height:1px;”><script> PARSELY = { autotrack: false, onload: function() { PARSELY.beacon.trackPageView({ url: “https://cronkitenews.azpbs.org/2025/11/24/mlb-injuries-oblique-trend-basebal/”, urlref: window.location.href }); } } </script> <script id=”parsely-cfg” src=”//cdn.parsely.com/keys/cronkitenews.azpbs.org/p.js”></script>

Canonical Tag:

Copy Tag

Article Content:

Oblique injuries rising in MLB: Why it’s happening and how to reduce injury risk

Jack Janes, Cronkite News

November 24, 2025

PHOENIX — Atlanta Braves prospect Nacho Alvarez Jr. chased a slider outside of the strike zone, and it chased him from the lineup for two weeks.

As Alvarez reached out with his swing, he felt a sharp pain in his side.

“My left side just blew up,” Alvarez said.

Infielder Alvarez, 22, was sent to the injured list with a strained oblique, an injury that is becoming more common among hitters with each passing year.

An Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine study looked at abdominal injuries that hitters in Major and Minor League Baseball sustained from 2011 to 2021 and found that the number of oblique injuries grew steadily over the decade-long span. The study also found that oblique strains were the third-highest time-loss injury in baseball over that stretch, only trailing hamstring and rotator cuff strains.

In 2011, there were 61 oblique injuries sustained by hitters across MLB and MiLB. In 2021, that number skyrocketed to 112.

“The main abdominal muscles that people tweak, especially when they’re doing high rotational activities, like swinging a bat or throwing a baseball, are your intercostals,” said Zachary Tenner, Mount Sinai Hospital physician and co-author of the study. “So the muscles are like right between your ribs, and then your oblique injuries, the oblique muscle sits on top of the intercostal.”

The rise in oblique injuries has raised questions as to why this is happening. There could be a variety of factors, but there is one main culprit.

Bat speed.

Similar to how there is a correlation between the rise in velocity and a rise in pitchers’ arm injuries, the increase in oblique injuries could be linked to the rise in emphasis on hitters’ bat speed. Pitching velocity has been tracked consistently in MLB since 2008, while bat speed has only been made public since 2023. But that doesn’t mean that bat speed was never tracked prior to 2023.

In 2014, a company called “Blast Motion” released the first bat sensor that tracked a hitter’s swing speed, swing path and time to contact. Today, teams and training facilities use various companies such as Rapsodo, HitTrax and others to measure everything about a player’s swing.

Driveline Baseball, a training facility with locations in Scottsdale, Seattle and Tampa, works with baseball players of all levels. Professionals flock to it during the offseason because it is analytically driven, coupled with the resources it provides to athletes.

“The fact that we have a motion capture lab here and all our facilities that can actually track the bat through space, that kind of technology becoming more prevalent has obviously made it a lot easier because it’s really hard to train something if you can’t objectively measure it,” Driveline Baseball hitting trainer Eric Kozak said.

With so much information readily available, numerous hitters are spending their offseasons trying to gain an extra mile per hour or two of bat speed to increase their power. The constant chase to swing harder can also put the player at risk of injury.

Boston Red Sox first baseman Triston Casas tore the cartilage between his rib cage and sternum after a swing early in the 2024 season. Casas told The Athletic when he was put on the injured list, “(The doctor) pretty much chalked it up to me being so big, rotating so fast, so many times that I created a car crash within my body. It was a matter of time before this happened. He said it was something similar to like a pitcher needing Tommy John, just an inevitable thing that was going to happen sooner or later.”

As sports medicine and science continue to evolve, athletes are becoming bigger, faster and stronger. Although athletes are reaching new heights, it’s important to remember the body’s limitations.

“The athlete has changed, the training techniques have changed, the knowledge around everything has changed,” Arizona Diamondbacks catcher James McCann said. “For the better, right? As far as the product that we’re receiving on the field, you got guys throwing harder than ever, you got guys hitting balls harder than ever.

“But I think that with all that, and the evolution of bat speed, I think the human body is still the human body. I think that at times we’ve reached the max potential of what the human body can handle. When you start reaching that threshold, something is going to go and then leads to different types of injuries like the oblique injuries.”

A hitter’s bat speed can be impacted by where they make contact with the ball. Hitting philosophies have changed over time, and in today’s game, hitters try to make contact more out front so they can pull the ball in the air, allowing them to hit for more power.

The further out front a hitter makes contact with the ball, the faster the bat speed will be.

“When someone’s pulling the baseball like that, that’s just a general higher rotational velocity that they’re providing that they put on the ball as compared to somebody going the opposite way,” Tenner said. “So if you’re looking at somebody like Joey Gallo versus Luis Arráez (both free agents), Joey Gallo is predisposed to getting this kind of injury because he’s rotating at such a higher rate versus someone else that’s trying to slap a ball the other way.”

Gallo is a former slugger who was notorious for selling out for power, trying to hit fly balls to the pull-side. By doing so, Gallo always had very low batting averages and struck out more than most, but he was still a dangerous hitter because he could hit a home run at any moment. His bat speed in his last season in 2024 was 72.4 mph. A versatile outfielder/infielder, Gallo recently announced his intention to convert from a position player to a pitcher.

Arráez is the complete opposite. He lets the ball get deep and peppers soft line drives to the opposite field for singles. He rarely strikes out and never hits for any power, leading to three-straight batting titles along the way. His bat speed in 2025 was 62.6 mph, the slowest in baseball.

They are two very different hitters, but both yield similar overall offensive results. On-base plus slugging percentage, better known as OPS, is a very common statistic that measures a player’s overall offensive output. Gallo’s career OPS is .775 and Arráez’s is .777.

So if players like Gallo and Arráez can have two completely different bat speeds with similar offensive outputs, why do hitters risk injury by trying to increase their bat speed?

Arráez is an exception, not the rule. He gets away with it because he has elite bat-to-ball skills that are unbelievably difficult to replicate. In the 2025 season, Arráez made contact with 94.7% of the pitches he swung at. The league average is 75%.

“There are no qualified hitters this year on Baseball Savant that swing under 62.6 (miles per hour) on average,” Kozak said. “Luis Arráez, Steven Kwan and Jacob Wilson are the three slowest swings and they’re 62.6 to 63.9 on average bat speed. But those guys are also crazy elite bat-to-ball guys that, for most humans, is not a realistically attainable skill to match them.

“If you swing 58 miles an hour, there is no comparable big leaguer because nobody with that low of bat speed has made it to major leagues, much less been successful, so it probably behooves you to get inside of the range where there are good hitters, particularly where there are a lot of good hitters. Trying to chase the outlier is rarely a recipe for success and just having all that information so available makes people understand its value but also dedicate their training economy accordingly.”

With the exception of the very few players similar to Arráez, there is a relationship between higher bat speed and better results.

In 2025, the MLB-average bat speed was 71.8 mph. Baseball Savant classifies a “Fast Swing” as a swing that is 75 mph or faster.

MLB hitters hit .313 with a .631 slugging percentage with fast swings last season while swings below 75 mph yielded a .250 batting average and .380 slugging percentage. Fast swings also produced a 54.7% hard-hit rate whereas the slower swings had a 37.2% hard-hit rate.

Meanwhile on the bottom of the list, only four of the 10 worst OPSs in baseball had league-average or better bat speed. New York Yankees shortstop Anthony Volpe’s 72.6 mph bat speed was the highest of the bottom-10 OPS list.

“The easiest way to put it is that it really sets both your floor and ceiling as a hitter,” Kozak said. “If you swing faster, that means that every ball you hit is going to be hit harder. You have more potential energy at your disposal to transfer to the baseball.

“It’s about the margin for error that peak (bat speed) affords you as a hitter. It’s really hard, especially at higher level baseball, like professional and big leagues. Pitchers are really good. Their stuff is nasty. It’s really hard to consistently be on time and hit pitches well. For the luxury of an increase in margin for error where you can miss a ball and still be productive is pretty crucial.”

Kozak characterizes it as a cost-benefit and risk-reward evaluation for each player. With today’s technology, teams and coaches can project what a hitter’s production could be if they lost or gained a certain amount of bat speed. These projections can help players guide their decisions as to how much they need to focus on bat speed training in the offseason.

“We can say like, ‘Hey, if you can gain two miles an hour bat speed this off season, it’s probably going to be worth $4 million a year versus like if you don’t you’re going to make what you made this year and if you lose bat speed you’re going to make $5 million less or you won’t be in the big leagues anymore,’” Kozak said.

It is no surprise that oblique injuries can be linked to bat speed, because the abdominal muscles are pivotal for generating power in a swing. More specifically, the lead-side oblique of the hitter is the main source of generating power among the abdominal muscles. Lead-side oblique injuries accounted for 71.4% of all hitter’s oblique injuries from 2011 to 2021, according to the study.

The lead-side is the side of the oblique that is opposite from the player’s dominant side. A right-handed hitter’s lead side oblique is his left oblique, and a left-handed hitter’s lead side is his right oblique.

Hitters are always going to be at a higher risk of injury when they are swinging at max effort, which is why proper training techniques are important to limit that risk. Training for higher bat speed, like most physical improvements, begins in the weight room.

“It starts in the weight room with single segmented, single-sided rotational activity with force and also a combination of mobility, making sure that our (thoracic) spine and our torso rotates the way it should, so then those muscles aren’t notoriously tight,” Arizona State associate athletic trainer Jesse Lowman said.

Russian twists, cable rotations and side planks are just a few examples of abdominal exercises baseball players typically use to build core strength. A strong and explosive core often results in explosive swing speeds.

In the batting cages, there are a variety of ways to increase bat speed. On top of that, no two hitters are the same. Every player has a different swing and body that will react differently to the same teachings. That is why it’s imperative to find drills that will work for each specific player.

The most common and “old-school” drill is using a heavy bat. A professional baseball player typically uses a bat during a game that weighs between 29 and 34 ounces. In the cages when they are trying to add bat speed, they may use a heavy bat that weighs over 40 ounces. Heavy training bats come in a variety of sizes that can reach up to 60 ounces.

Another drill hitters can do is called “stick-ems,” where hitters take a normal swing but stop their bats at where the point of contact would be. By stopping the swing as quickly as possible, the drill activates hitters’ core muscles and makes them stronger.

Sometimes, the problem can be mechanical.

“The idea is you really want to identify what is the low-hanging fruit in terms of creating an adaptation and increasing bat speed,” Kozak said. “You’ll see a guy who’s extremely powerful and strong and produces a ton of force but their swing mechanics are really lacking and inefficient sequencing, poor movement patterns where a lot of the bat speed is gained.

“It’s not that they can’t produce a bunch of force when they swing, it’s that they’re not producing it correctly, they’re not transferring energy efficiently up the chain. They’re basically just relying on their arms to swing. That guy needs a large dose of mechanical work to improve his kinematics and transfer energy more efficiently because he already has a ton of force output, but he can’t transfer it out to the barrel.”

When in the batting cages, Kozak believes the most important thing is swinging with intent. A hitter swinging with intent means they are swinging the bat as hard as they can with control, in hopes of hitting for power. By training with intent, it makes the hitter’s obliques build a tolerance for more violent swings in the game.

At Driveline Baseball, instructors tend to work with hitters six days a week. Kozak said that three of those days are considered “bat speed days.” Those are the days that the primary focus is to increase bat speed and not worry as much about contact.

One of the drills that Driveline Baseball does on those days is called a bat speed derby, in which the players compete with themselves by swinging as fast as possible with every swing. Kozak said another benefit from the bat speed derbies is that it accelerates the motor learning process of the hitters due to the immediate feedback and the ability to make rapid adjustments.

With numerous exercises and drills to increase bat speed, it is vital that players and coaches closely monitor workload.

“You can just do so much that you put the obliques in this fatigued state, and then you try to go swing a bat to try to catch up to the 95 mile an hour fastball and you have a chance of hurting it,” Lowman said. “We have guys that want to go in and take 1,000 swings a day after practice, and that’s an exaggeration, but we have to tell our hitters, ‘You swung enough today, do not go. You will not swing any more today.’

“Because again, you keep swinging a bat, eventually there’s muscle fatigue and you’re at risk for injury.”

If a player does hurt his oblique, returning to the field is a tedious process.

The most efficient way to rehab a strained oblique is to rest as much as possible. It can be a long process because the oblique muscles are so large and strong to begin with, meaning that when obliques are hurt, the injury is usually significant.

“Because they are a core muscle, and a muscle that helps keep us upright, moves us even reaching for a cup in the cupboard, we’ll just never get the chance to shut them off,” Lowman said.

“A hamstring strain, I could technically put them on crutches and really give the hamstring a break for a few days to start the healing process. The oblique doesn’t get that because every time you breathe, the oblique works, every time you take a step, the oblique works. So obliques are hard to rehab just on that premise alone.”

Lowman said once the player is able to get up in the morning and do everyday activities without issue, then the rehab process begins with simple range-of-motion and body weight exercises. From there, normal baseball activities and weight training begins once the player no longer feels pain.

The severity of the strain and a player’s pain tolerance generally dictates recovery time. Depending on those factors, Lowman said he has seen oblique injuries keep players down for 10 days, but he has also seen some sidelined for up to seven months.

Injuries are the worst things about sports. They obviously are not good for the players, as it causes pain and can cost them accolades and future earnings. But it’s also not good for fans who want to see the game played with the best players possible, and that level of competition reduces when players are unable to suit up for games.

Team training staffs and players do all they can to limit the injury risk, but sometimes injuries are unavoidable.

The conversations surrounding how pitcher’s arm injuries can be attributed to pitchers throwing as hard as possible has been thoroughly exhausting, and now the same questions are being raised about hitters hurting their obliques by swinging as hard as they can.

Hitters are forced to decide whether chasing bat speed is worth the injury risk for their career. It’s an unfortunate reality, but the benefits of higher bat speeds are undeniable. So hitters almost have no choice.

“To hit people that are throwing so hard nowadays,” Alvarez said, “You have to swing hard.”

This article first appeared on Cronkite News and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copy Content

Tracking snippet:

Copy Snippet