Ben Brown‘s trajectory over the course of 2025 landed as one of the more enigmatic episodes of the 2025 Chicago Cubs.

On one hand, his mix of an upper-90s fastball and destructive knuckle-curve led to some strong results in matters of balls and strikes. Brown’s 25.6 percent strikeout rate sat in the 73rd percentile and his 6.8 percent walk rate finished in the 71st. Of course, on the other hand, he got touched up in the contact game to the tune of a sixth-percentile hard-hit rate (47.3 percent) and a seventh-percentile barrel rate (11.4 percent). That somewhat paradoxical mix left him with an unsightly 5.92 ERA, an eventual demotion to Iowa, and larger questions about his future role as a member of this pitching staff. Namely, the following question: Is there a path toward continued starting opportunities for Ben Brown, or is he destined for relief work in some form?

While not initially a rotation candidate, a strong spring performance during the exhibition season afforded Brown a legitimate shot at being part of the starting five from 2025’s outset. A competition that seemingly came down to he and Colin Rea resulted in Brown winning the job on the heels of the tantalizing stuff wrought by that two-pitch mix. While Rea became a necessity within the rotation in his own right, Brown held onto regular duty for most of the first two months of the season.

By the end of May, however, Craig Counsell experimented with an opener given Brown’s struggles that resulted in starts in which he allowed five, six, six, and eight earned runs. Injuries necessitated continued turns, but Brown found himself out of the starting five permanently by the end of July. From there, he was deployed in relief (primarily as a bulk arm) for the remaining 18 of his 106 1/3 total innings for the year.

Split between starting and bullpen work, the following is how Brown’s numbers shook out in 2025:

As a Starter: 75 2/3 IP, 6.30 ERA (4.47 FIP), 23.8 K%, 6.7 BB%, .362 wOBA against

As a Reliever: 30 2/3 IP, 4.99 ERA (3.10 FIP), 30.5 K%, 6.9 BB%, .300 wOBA against

Despite the innings sample heavily leaning toward the starting side, there’s immediately sort of a clear picture as to which path makes more sense for Brown. Such an idea is furthered by a 4.19 ERA the first time facing hitters as a reliever against a 5.70 ERA the first time facing hitters as a starter. His 35.3 percent strikeout rate the first time through the order as a reliever was also his best individual mark in any trip through the order, regardless of role. In relief, Brown was also able to work at an eight-percent dip in hard contact (by FanGraphs‘ definition), a decreased fly-ball rate, and a subsequent decrease in his homer-to-fly-ball ratio.

In a number of different ways, the numbers pretty easily support Ben Brown making a transition to full-time relief duty. But it’s also not as simple as “this guy is performing better in this scenario, so we should drop him into said scenario full time.” Instead, the reason for keeping Brown in relief is the same as it’s always been: his failure to develop a third pitch. Brown attempted to incorporate a changeup as the season wore on. It was a journey that would prove to be unsuccessful, not only in terms of usage, but outcomes.

Brown threw the changeup just 4.5 percent of the time in 2025, with its usage peaking at 10 percent in July. By the time he entered regular work out of the bullpen, it dropped to 3.5 and 4.3 percent usage in the season’s final two months, respectively. And it’s not just a matter of his struggling to incorporate the pitch. It’s what happened when he did.

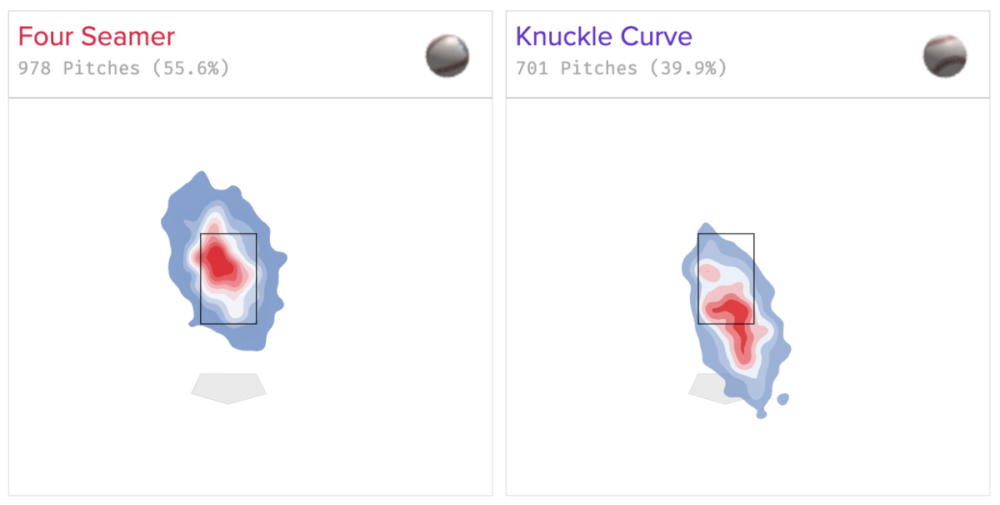

Even with a smaller sample in its use, Brown’s changeup was touched for hard contact exactly 50 percent of the time, with a barrel rate of 20 percent and a fly-ball rate lingering around 30. Obviously, none of those trends represent a recipe for success. On just about every level, Brown struggled to maintain anything effective with that pitch despite the movement he was able to generate with it. The following is the contour of each of Brown’s two primary pitches from 2025 (the fastball and the knuckle-curve):

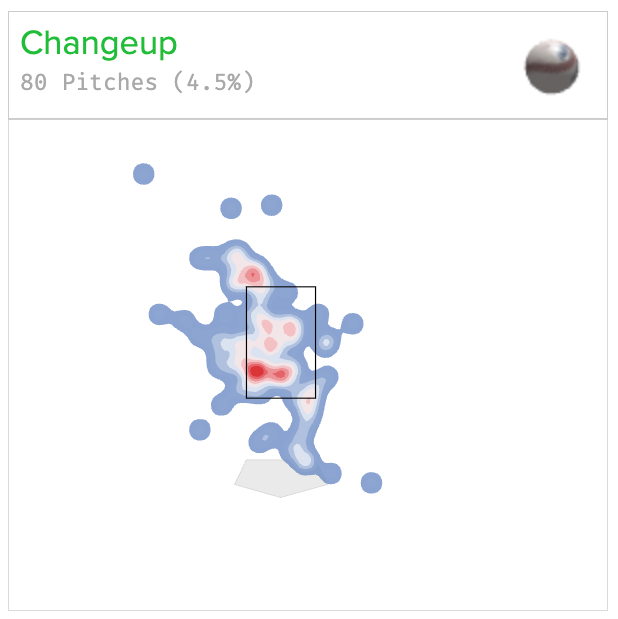

For the most part, that’s exactly how those should look. You want a concentrated area with a pitch like a fastball. Something like a knuckle-curve is going to expand that concentration a little, but the vertical nature of the contour’s trend still reads in exactly the way it should. And then you get to the changeup:

Again, it’s not only a matter of Brown’s inability to know when to use the pitch, but throwing the pitch at all. It’s not that it got touched up by opposing hitters—it’s that he had very little command over the pitch at large. Part of that is the nature of trying to add a pitch on the fly. The pitch flailing so erratically doesn’t lend itself to much confidence that Brown would be able to do it over the long-term, either.

Without that third pitch coming to fruition, there’s no argument for providing Brown with an opportunity to get back into the starting five. The other two pitches would have to be elite. And while the knuckle-curve might offer that (121 Stuff+), the fastball does not (84 Stuff+). Barring some massive development in the lab this winter, it almost becomes impossible to justify as a result.

If the splits don’t say so, the absence of a meaningful third pitch certainly does.