Welcome to part three of North Side Baseball’s offseason series covering the 1918 Chicago Cubs. You can find part one here and part two here.

Last time we checked in, in part two, the Cubs were chasing the New York Giants in the standings through the end of May, but were making up ground quickly. Even though they lost Grover Cleveland Alexander to the military, the pitching staff was rolling behind Hippo Vaughn. The offense was doing their part, thanks to sterling performances from Fred Merkle, Les Mann, Dode Paskert, and rookie shortstop Charlie Hollocher. In today’s piece, we’ll take a look at the career and life of Hollocher.

[Please be warned that this piece will discuss topics like mental illness and suicide. I tried to present these events as they reportedly happened in a way to shed light on the tragic tale of Charlie Hollocher, while paying homage to the person and player that he was.]

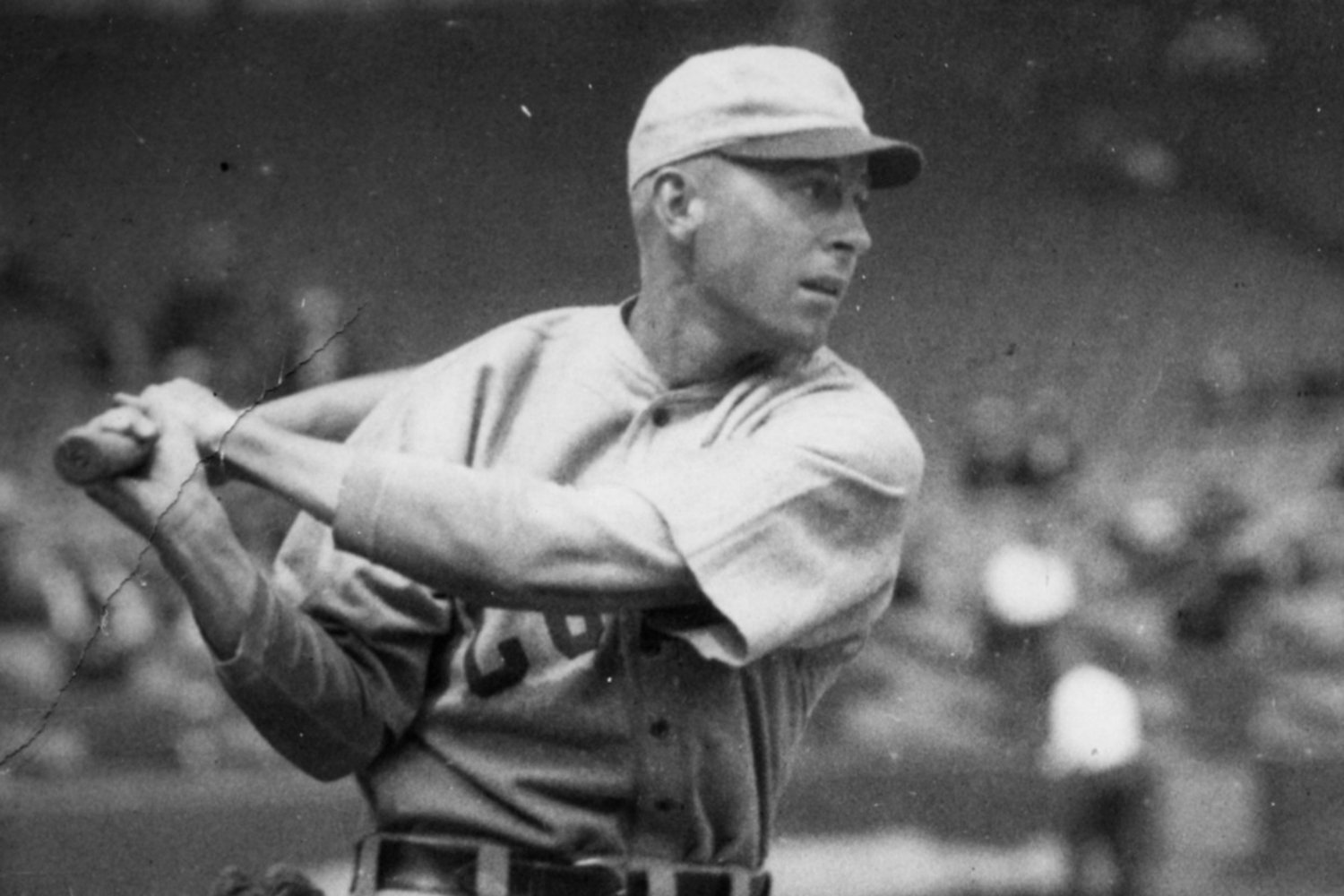

Charles Jacob Hollocher was born on June 11, 1896, in St. Louis, MO. According to his Society for American Baseball Research biography, Hollocher learned the game from sportswriter John B. Sheridan. This led Hollocher to the minor leagues, where his contract was eventually purchased by the Cubs before the 1918 season.

Reportedly, the Cubs were trying to deal the young shortstop for Rogers Hornsby to no avail. That would be a blessing in disguise, as he would go on to hit a team-leading .316 in the 1918 season. His 5.5 FanGraphs WAR was fourth in all of baseball.

Unfortunately for Hollocher and the Cubs, that 1918 season, when he was just 22 years old, was close to his peak. His average dropped to .270 in the 1919 season. Then came the health issues.

According to The Capital Times, on June 9, 1920, he was pulled from the lineup with what doctors called ptomaine poisoning, or as it is now more commonly known, food poisoning. He would go on to hit .383 in 33 games following his return to the lineup, until the same thing would happen again. Hollocher was absent from the lineup from July 14 through July 24, with the Springfield News Sun reporting on July 21 that he lost 15 pounds during another bout with ptomaine poisoning.

He returned to the lineup on July 24 and 25, however, that would be the end of Hollocher’s season. Per his SABR biography, it was announced on August 15 that he was hospitalized, and then on August 17 that he was released. He finished the season with a .319 batting average, but only managed to play in 80 games and notch 369 plate appearances.

Despite all of that, Hollocher would, again, rebound. He hit .315 for the Cubs across the 1921 and 1922 seasons. Unfortunately, the star shortstop fell ill again before the 1923 season, with the Chicago Tribune reporting on February 16 that he was “down with a mild attack of flu.” On March 31, the Tribune followed up that Hollocher was “confined to bed at his home here, ushering from after effects of an attack of influenza last February.”

This would delay the shortstop’s 1923 season debut until May 11, where he showed no signs of being hampered, sporting the typical high batting average that fans had come to expect from Charlie Hollocher. He was hitting .342 with a .410 on-base percentage on July 23. Alas, that was the last we’d see of Hollocher in 1923. The Associated Press quoted Hollocher on August 4 as saying that he was “feeling pretty rotten and have made up my mind to go home, take a rest, and forget baseball for the rest of this year.”

It was reported in the Tribune in November of that year that “stories immediately started that Hollocher’s real purpose in ‘jumping’ the team was to force a trade that would send him to the Cardinals.” It was clear that people were becoming frustrated and speculating about the star shortstop’s consistent absence.

Hollocher would again rejoin the Cubs for the 1924 season after a brief contract holdout, amidst reports that he was finally fully healthy. Despite those reports, he was not his typical self. He was hitting for just a .245 batting average through August 20 before he went missing from the lineup again. The Tribune followed up with the following on September 5, while expressing doubt that he would ever play again:

”Hollocher is a sick young man, and his failure to play regularly for the last couple months was due to that and nothing else. Several weeks ago he requested that he be excused for the balance of the season, but was urged to stay until the club could get a utility shortstop.”

This was, indeed, the last time anyone would see Charlie Hollocher on a professional baseball field, despite several attempts at a comeback. It is reported in his SABR biography that Hollocher returned home to St. Louis where he operated a tavern, worked as an investigator for the prosecuting attorney’s office, and also worked as a watchman at a drive-in movie theater.

This all, unfortunately, led to tragedy on August 14, 1940. According to multiple reports at that time, Charlie Hollocher was found dead, in his car, with a gun wound and a 16-gauge shotgun lying beneath one of his arms. There was a note on the dashboard to call his wife. He was 44 years old.

According to his SABR biography, his wife said he was recently complaining of severe abdominal pains. It is also quoted that the Chicago Herald-American wrote the following:

”The death of Charley Hollocher at his own hand came as no surprise to baseball folks who knew the one-time Cub shortstop when he was rated the top man at his position in the big leagues. Even when he was breaking in at Portland, Oregon, Hollocher was a moody, neurotic boy.”

There are multiple layers to the tragedy that was Charlie Hollocher. It would seem, through multiple reports, that the young man was suffering from some sort of chronic illness in his stomach, and not everybody took that particularly seriously. We’ll never truly know what happened, but it’s easy to imagine that the illness itself, never finding a true diagnosis, and not always being taken in earnest, took a toll on him mentally.

Through it all, Hollocher’s .304 career batting average is 18th all-time in the history of the Chicago Cubs among players that had at least 1,000 plate appearances. His 23.7 fWAR in just seven seasons, some of which were shortened due to the illness, is 32nd. A lot of this has been lost to history. Personally, I had never heard of Hollocher until researching this series. It’s hard not to imagine what could have been.

We are all fortunate to live in a time when both physical and mental health are given much more care, though it is still not taken seriously enough. Let the story of Charlie Hollocher serve as a reminder that you never know what another human being is going through. Be kind to each other.