I took the Metro Red Line into downtown Los Angeles late in the afternoon on September 30, wearing a faded, cotton 1952 Cincinnati Reds jersey. I unbuttoned the Chuck Harmon throwback—a nod to the first Black player for the Reds, remembered by very few, even in Cincinnati—at Union Station to better show off the shirt beneath it which depicted the most iconic Red, Pete Rose standing with his hands in the air, having reached base safely, his nickname emblazoned on the black shirt in white lettering below the image: “Charlie Hustle.”

On the Metro, I was the only one wearing Reds merch; the other passengers, also bound for the Dodger Stadium Express, hurried out of the subway station beneath the famous art-deco train depot, children clutching blue foam fingers and oversized foam headgear shaped like baseball caps. On the bus, I watched the cityscape slip by, the hills shimmering, the heat still holding even though fall had officially begun a week and a half before. As we entered Chavez Ravine, Major League Baseball’s jewel of the west came into view. I felt a sort of grim certainty: My hometown team was about to get trounced.

I told myself this wasn’t fatalism so much as realism. The Cincinnati Reds had done about as well as one could expect under first year manager Terry Francona, no stranger to the postseason, backing into the final National League wild-card spot with an 83–79 record, the weakest of any team in the playoffs. And yet here I was, schlepping from Wilshire/Vermont on the train to catch the Dodger Stadium Express at Union Station, for what would almost certainly be a short ride into the postseason against the most expensive roster ever assembled.

These numbers aren’t hyperbole. In 2025, the Dodgers’ payroll sat around $340 million, their luxury (or “competitive balance”) tax bill—by some estimates, over $150 million—exceeding the total payroll of the Cincinnati Reds, roughly $115 million. (The Reds’ owners, the Castellinis, are the “poorest” owners in baseball, their grocer fortune only worth a paltry $400 million.) Shortly after missing the playoffs in consecutive seasons under former-Yankees-skippers Joe Torre and Don Mattingly, owner Frank McCourt sold the Los Angeles Dodgers, on March 27th, 2012, to Guggenheim Baseball Management, in the wake of a personal financial crisis; he had taken on massive debt to buy the team and used team revenue to fund his lavish lifestyle and contentious divorce settlement. Already armed with fresh capital under their new owners, the Dodgers signed the most lucrative regional sports cable programming deal of all time, agreeing to a twenty-five-season, $8.35 billion deal with Time Warner Cable in January 2013. They last missed the postseason under their much less lucrative Fox Sports West deal in 2012, the season after McCourt sold the team. These sets of facts are not unrelated.

Every team now has advanced, post-Moneyball metrics, global scouting networks, a farm system stocked with international talent, in a game that has long since gone global. But the Dodgers have the cold hard cash and international brand identity, fortified since the 1990s, to effortlessly sign the best international stars out of Japan and Korea upon arrival (Hideo Nomo, Chan Ho Park, Roki Sasaki, Yoshinobu Yamamoto) or later, when they grow tired of their first destination (Shohei Ohtani), for sums that would make most other front offices break into a sweat. My quiet dread came from knowing what that meant, from having watched enough Octobers to recognize the inevitability that money buys.

Game 1 began at six o’clock in the evening, the light just starting to fade behind the left-field pavilion. The Reds sent their injury prone ace, Hunter Greene—brilliant and imposing when he’s right but mentally fragile—to the mound and things quickly unraveled. Ohtani hit a leadoff home run, the sound of the bat cracking through the warm air like a warning shot. By night’s end, the Dodgers had hammered five more, fifteen hits in all, turning the game into a kind of demonstration. I sat in the top deck surrounded by blue, watching the dream of the underdog dissolve inning by inning. The Reds scratched together a couple of runs late, but the final was 10–5.

I changed jerseys for Game 2—a vintage 1902 Reds jersey, with large pockets on the sides and a collar-neck, simple red stitching of “Cincinnati” across the chest—almost as a talisman. The ridged collar made me feel connected to the long, winding past of Cincinnati baseball, to an era when Cincinnati was a larger city than Los Angeles and the term small market team had yet to be invented. I rode the Red Line again, boarded the Express, and settled into my seat with the same ghost of dread: that this would be short, that the young Reds would be overmatched, that the payroll gulf would again decide our fates.

Game 2 began with promise. The Reds looked alive and took an early lead. But the Dodgers struck again, their depth, patience, and relentless pressure coming to bear on Reds’ starter Zach Littell, acquired mid-season from the Tampa Bay Rays for just this sort of moment. The Reds’ promising first base prospect Sal Stewart, in the big leagues for less than six weeks, had a clutch RBI hit early in the game but gave it back with a costly error. This time, I made my way back to the Dodger Stadium Express early; if you aren’t on the first train to leave the stadium, you will inevitably get caught in snarled traffic as everyone heads to the exits, extending your trip by an hour. I got wind of the final score of 8–4 as my bus reached Union Station; the Reds were eliminated in a sweep. The walk back to the subway, through Union Station’s stately halls, after the game felt cold. I was the lone Reds fan on the platform, a wisp of white and scarlet among a sea of blue.

From there, the Dodgers surged as expected, beating Philadelphia, then Milwaukee, culminating in a World Series triumph over Toronto. The Phillies had posted the better regular-season record, yet the Dodgers cast them aside rather easily, breaking the Phils in four games by taking the first two on the road and silencing Philadelphia’s deadly, high-priced offense. The Brewers’ brilliant young pitching wilted under the weight of the Dodgers lineup, which featured at least three surefire hall of famers—Ohtani, Mookie Betts, and Freddie Freeman—and several more all-star caliber players, including Teoscar Hernandez and Will Smith.

The World Series against the Blue Jays deserved its epithet of “Fall Classic,” featuring seven games of back-and-forth heroics and including two of the best baseball games I or anyone alive have ever seen. Within a week the eighteen-inning, six-and-a-half-hour Game 3, was eclipsed by the eleven-inning contest that concluded the series, improbable as its many twists and turns were, complete with desperate plays at the plate and reversal-of-fortune ninth-inning home runs. That it ended in LA’s favor, despite the Dodgers hitting just .203 on the Series, the lowest batting average for a winning team since the 1966 Baltimore Orioles, suggests that perhaps, in a city that has been through so much—wildfires, entertainment-industry strikes, the exodus of film and television production to cheaper states—Los Angeles was simply destined. It deserved a reason to cheer, needed a story to believe in. Nearly fifty thousand jobs in the entertainment industry, which still powers the city, have been lost since the beginning of 2023. In that vacuum, the Dodgers have found themselves one of LA’s last shared civic myths. And maybe that’s why the crowd’s chants felt almost religious. The franchise gave them something tangible, a chance to be a part of a whole, even if it was all built on inequity. But a more bitter takeaway lingered with me: This was not the victory of a beleaguered city over the difficulties of a brutal year in paradise, but of capital over everything else.

I found socialism not in the pages of Marx, but in box scores. Growing up in Cincinnati in the 1990s, I learned early how unfair baseball could be. The Reds were a proud franchise, the oldest in all of American professional sports, who have had a hold on the city and its citizenry that is, or perhaps was, uncommon. But the newspapers began to inform me, as a 12-year-old in 1996, that the Reds would field a diminished team because, well, they couldn’t afford to keep their players any longer. That $30 million, .500 squad, Ray Knight’s first in what was a woefully short tenure on the Reds bench, lacked several of the key players from Davey Johnson’s 1995 playoff team—beer bellied pitcher David Wells, flame–throwing catcher Benito Santiago, reliable outfield bat and physique king Ron Gant. I and other Reds fans would have to temper our expectations and make do with less. That 1995 team swept the Dodgers in the Division Series, in the franchise’s last playoff–series victory to date, and it feels like the Reds, and other franchises like it, have been fighting forever uphill since, constrained by paltry regional television money in an economic system that prizes market size over merit, the occasional pluck and organizational innovations of Oakland or Tampa Bay being the exceptions that prove the rule.

The Reds, unlike the Dodgers, never pursue high-priced free agents and struggle to retain all but their very best locally canonized players, such as Joey Votto, Ken Griffey Jr., or Barry Larkin, when the bill eventually comes due. Johnny Cueto, the best pitcher the team has developed in a generation, was traded on the eve of a big contract; so too was Luis Castillo a few years later. Gant and fellow outfield bopper Greg Vaughn were let go after single, heroic seasons in red. Trevor Bauer, briefly a Cy Young winner on the team, was also gone after a year, signed by the Dodgers to a massive contract, although he was soon out of the league, in the wake of #MetToo; perhaps the Reds dodged a bullet there. The same cycle has now repeated for a generation: develop, contend briefly (maybe), disperse. Watching it play out, year after year, as an adolescent and young adult, taught me something about capitalism long before I had the language for it.

The contrast between MLB and the NFL and NBA is instructive. Green Bay and Oklahoma City can compete on near-equal footing with New York and Los Angeles because of revenue-sharing and salary caps in their respective sports. Baseball has refused such egalitarianism. There is no real ceiling, no redistributive mechanism—only the soft luxury, or competitive, balance tax, a slap on the wrist for the wealthy. Watching the Reds trade away their best players while the Dodgers, Yankees, Red Sox, or Cubs acquire everyone else’s, often feels like a fantasy baseball civics lesson.

When the Dodgers spend nearly $500 million on salaries, including deferred payments and tax penalties, one sees the American way of life come into focus anew: a few at the top thriving in the abundance of Ezra Klein’s wet dreams, the rest of us surviving on scraps. Of course this matters little to Dodgers fans, for whom the team is a class unifier; when the Dodgers finally closed out Toronto in Game 7, the city erupted with a force that felt both cathartic and preordained, hipsters and cholos taking to the streets in equal measure. The scene on the streets of Echo Park that night was one of release: car horns echoing off the 101, fireworks bursting above raucous streets full of elated families and loud drunks, Waymos tagged with blue spray paint as far as the eye could see, strangers embracing in ecstasy.

The parade that wound down Figueroa and along 7th Street a few days later, players waving, confetti cannons booming, was proof that Los Angeles still knows how to perform joy. Although the Dodgers are baseball’s richest franchise, and their ownership consortium, a coalition of financiers and entertainment moguls who treat the team as both financial asset and civic theater, their fan base remains overwhelmingly working class and Latino, made up in large part of people from East LA, Pico Rivera, and Montebello. Standing among them, I saw undeniable, genuine love from the families chanting “¡Que vivan los Doyers!” but underneath it all lurks an unease that the organization has never quite resolved in its relationship with its brown fanbase.

The Dodgers’ story in this city begins with displacement. In the 1950s, when Walter O’Malley moved the team west, the city seized the land in Chavez Ravine under the guise of urban renewal. Mexican-American families who had lived there for generations were dragged from their homes, their neighborhoods bulldozed to make way for a new stadium. Public housing became private profit. The country’s most stately baseball stadium’s past is soaked in blood, a beauty built on the ruins of Palo Verde and La Loma, whose ghosts still roam the hills ringing the parking lot. The stadium’s panoramic splendor—downtown LA framed by palm trees, the San Gabriel Mountains beyond—sits atop erasure. The franchise rarely acknowledges it, except in vague plaques about the community that made room or some such platitude.

The Dodgers’ reputation as a progressive concern is overdetermined by Jackie Robinson having broken Major League Baseball’s color barrier on the team in 1947, when they were still located in Brooklyn. But it is complicated not just by the team’s destruction of the communities that predated its Los Angeles home of fifty-five years. There’s also Glenn Burke, the first openly gay major-leaguer, a Dodger outfielder whose exuberance and honesty cost him his career. The team offered to stage a sham marriage to quiet the rumors; when he refused, they traded him away. He invented the high-five, and they erased him from the record. Only decades later did the Dodgers gesture toward contrition, long after Burke died of AIDS. In my movie exec days, the job that first brought me to California, I tried to make a picture about Burke and his treatment at the hands of the franchise, produced by Jamie-Lee Curtis, but fear that the Dodgers and the MLB would never allow an honest version of the story to see the light of day put an end to its tortured development on the Bezos Plantation.

This past season, the Dodgers allowed federal immigration agents to use their parking lot for detention logistics and reprimanded a singer for performing the national anthem in Spanish. They market themselves as the team of Los Angeles’ working class while partnering with the same forces that harass and criminalize it. That tension—between the people’s team and the corporate monolith that it actually represents, empowers, enriches—is the moral heart of their story. TWG Global, the investment and holdings company cofounded by Dodgers’ principal owner Mark Warner, has a partnership with Palantir, whose surveillance tech is being used by ICE to kidnap children on their way to school and line cooks on their way to work as I type and as you read.

Fernando Valenzuela’s face adorned several signs at the parade and even more backs, his jersey ever-popular with fans despite the fact that he hadn’t taken the mound at Dodger Stadium for over thirty years, even before his death in August turned the season into an elegy. For many Mexican Angelenos, Fernando was the first baseball player who made them feel seen. “Fernandomania” in 1981 forced the team to recognize its Latino audience, to print tickets and programs in Spanish, to admit that its true heart lay east of the river. This championship in the wake of his passing felt like a requiem for Fernando, and for the idea of the Dodgers as something belonging to the people of the city as much as to a set of billionaires.

The Dodgers’ model, like the city’s, depends on endless escalation, infinite growth; more spending, more spectacle, more winning. The Reds, meanwhile, live on prayer and parsimony. Baseball is supposed to renew hope every spring, but hope requires the possibility of success which in turn requires that the illusion of fairness is at least strong enough to deceive. When you know the ending before the first pitch, fandom curdles into masochism.

I walked home through downtown, past the throngs in Ohtani and Betts jerseys walking the other direction—the parade would end at the stadium, where an even larger celebration would be held. The sun was high and clear, the temperature Los-Angeles perfect. I couldn’t help but be happy for everyone, because if you live here long enough, the Dodgers get into your blood. You may resist it and cling to your small-market loyalties, but the depth of the city’s love for the franchise seeps in. I’ve now gone to more Dodgers games in the past decade than Reds games in my youth. I’ve cheered Clayton Kershaw’s curveball as readily as I once did Jose Rijo’s. I’ve eaten Dodger Dogs I knew I’d regret and kneeled during the National Anthem in Kaepernick-esque protest while fifty thousand strangers, feeling something that borders on grace, stood and praised a flag that sometimes accepts them. Maybe that’s the contradiction I’ve been circling all along: Can you critique the machine and still be moved by its music?

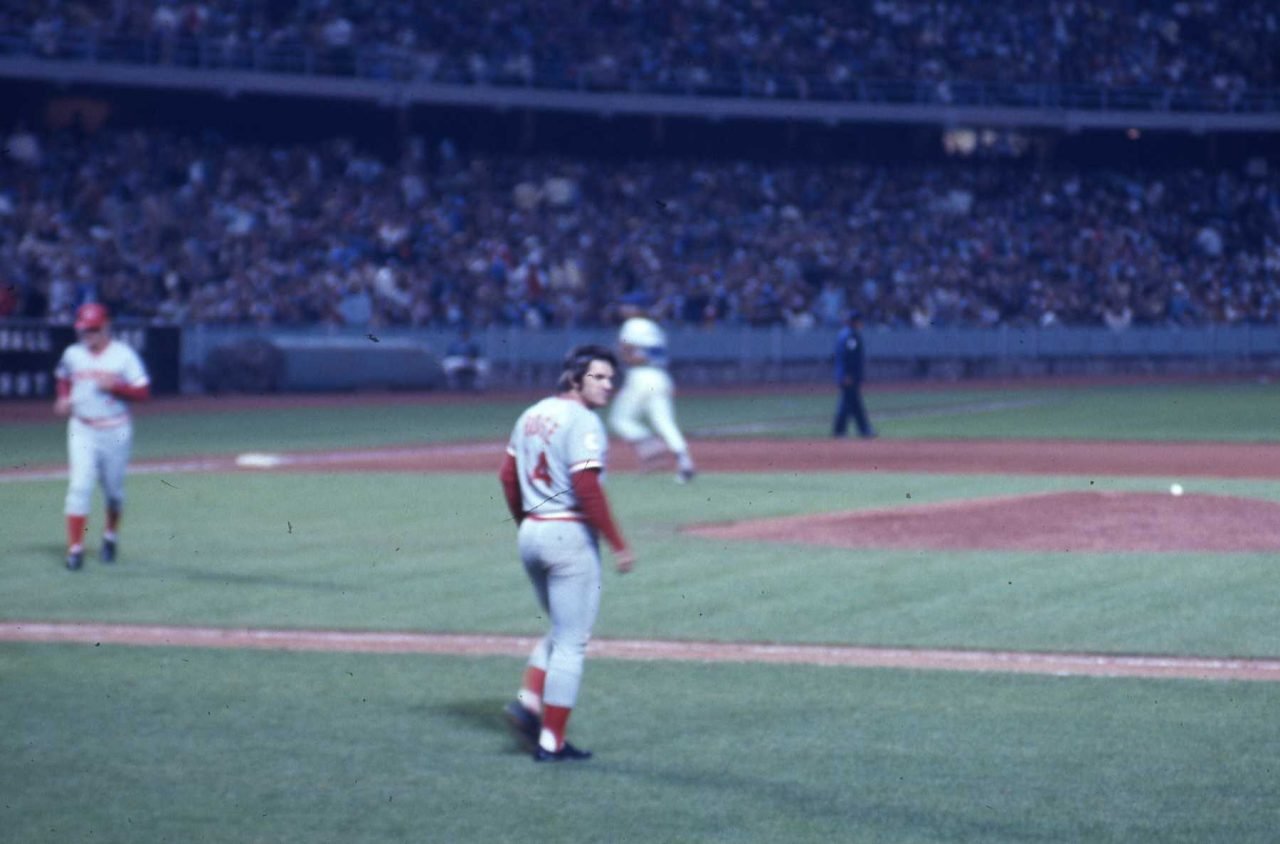

The first back-to-back World Series champ to emerge from the National League since the Big Red Machine of Rose, Joe Morgan, Johnny Bench, Tony Perez won its first title in Cincinnati fifty falls ago, is a Big Blue Machine, but it is made primarily of green. I used to believe baseball simply needed league socialism to save it: a salary cap, redistribution of local TV revenue, a national press less focused on holding up a mirror to the cities its own members live in. I still believe that. But watching the Dodgers hoist their trophy, I wonder if fairness in sports is even possible in a nation that’s spent half a century dismantling it everywhere else. Baseball mirrors its country: a pastime built on nostalgia, sustained by inequality. You can’t tell the Dodgers’ story without displacement and denial, nor the Reds’ without scarcity. When I go home, I see in Cincinnati’s redevelopment the same forces at work that once razed Chavez Ravine—speculation disguised as progress, revitalization that means removal. Our games promise community even as they replicate hierarchy. They let us imagine meritocracy while reminding us who can afford it.

If you like this article, please subscribe or leave a tax-deductible tip below to support n+1.