Here at Imaginary Rule Change Theater, we’re going to transport you to a big-league ballpark in 2030, where Julio Rodríguez has just jogged out to center field on Opening Day in Seattle. And what does he find?

It’s that fabled line he cannot cross. Literally.

Mowed into the grass is a dark green, cross-cut, curved line that runs across the entire length of the outfield at T-Mobile Park, positioned about 10 feet shallower than where the average outfielder plays now. Let’s call it the “This Is How We’re Saving the Doubles and Triples Line.”

We know what you’re thinking: The what? But rest assured, this is a line that has actually been discussed and debated within the inner sanctum of Major League Baseball. In fact, it was even drawn on real outfields and studied once in extended spring training.

Now here’s the reason you might see that line mowed into an outfield near you someday: The double is dying. The triple is practically dead. The old-fashioned gapper is now an endangered species. And the only way to save it is to regulate where outfielders can stand.

We apologize to all the outfielders and coaching staffs whose deep dives into defensive positioning could force this sport to take that drastic step one of these years. But we’re approaching the point where the league could have no choice, just as it concluded it had no choice but to tell infielders where to stand, when it banned the shift three years ago. Here’s why:

• According to Baseball Reference, the rate of doubles per game (1.59) fell this year to its lowest level in more than three decades (since 1992).

• Meanwhile, the rate of triples per game (0.13) plunged to a level that tied the lowest in history.

• So what does that mean? It means we’ve made nearly 1,500 doubles disappear since 2007. And we’ve made over 300 triples disappear since 2015.

DOUBLES

2007 — 9,197

2025 — 7,745

TRIPLES

2015 — 939

2025 — 628

If we go back to this century’s offensive heyday, which was roughly from 2006 to 2008, we’re talking about almost 2,000 doubles/triples a year that have vanished — mostly into outfielders’ gloves. It’s such a dramatic drop-off that we’ve reached a point where there were fewer doubles plus triples hit this season than the total of doubles alone as recently as 2019.

2019 — 8,531 doubles

2025 — 8,373 doubles + triples

Have you noticed? If you haven’t, you’re not alone. But if you have, we have the perfect description of what kind of shrewd baseball observer you very well might be:

A hitter!

Oh, those hitters have noticed, all right. I’ve been asking them about this for months. And boy, were they glad to learn somebody cared about this besides themselves.

“Honestly, it’s like no doubles (defense) out there every night,” said Alex Bregman. “You’ve got to hit it off the wall. It’s crazy.”

“They’re basically saying, ‘Here’s your single. Take it,’” said the Royals’ Vinnie Pasquantino. “They’re like, ‘If you want to bloop one in, we’ll give it to you.’”

THE ATHLETIC TO FREDDIE FREEMAN: “Has it ever been harder to hit a double?”

FREEMAN: “It’s hard. It’s hard just to get a hit.”

The Dodgers’ Cooperstown-bound first baseman knows he could be the poster boy for this entire conversation. After all, he’s led his league in doubles four times. In 2022-23, he averaged 53 doubles a year. Over the past two seasons, that fell to 37 a year.

He understands why that is, too. It has everything to do with how deep outfielders play now and how much information they have on where he’s likely to hit those balls that used to fill up his doubles column. As we’ll demonstrate, he was hitting under dramatically different conditions when he first reached the big leagues a decade and a half ago. Here are two examples:

First, here’s a laser Freeman smoked to the center-field warning track, at 103.2 mph off the bat, in 2016. It was (what else?) a double.

Now here’s a very similar rocket to the center-field warning track he hit this past season, at 103.1 mph. This one turned into (what else?) an out.

Here’s your official takeaway from what you just watched: The positioning, and athleticism, of the center fielder, Angel Martínez, in the second video was not an accident.

“I think it’s definitely different (than when he first came up), with all the data,” Freeman said. “Every day, right before I go out there, I get a card with where I need to play on each and every hitter. And it’s the same with the outfielders.”

He began to describe some of the aspiring doubles he has seen caught, all because of those cards, that data and those world-class athletes wearing the gloves. Every hitter has one (or 10) of those stories now. And why is that an issue? Ho-ho. We can’t wait to tell you exactly why.

The deep state

The Diamondbacks’ Blaze Alexander catches a deep fly ball hit by Alex Bregman. Outfielders are more athletic than ever, and positioned better thanks to analytics. (Christian Petersen / Getty Images)

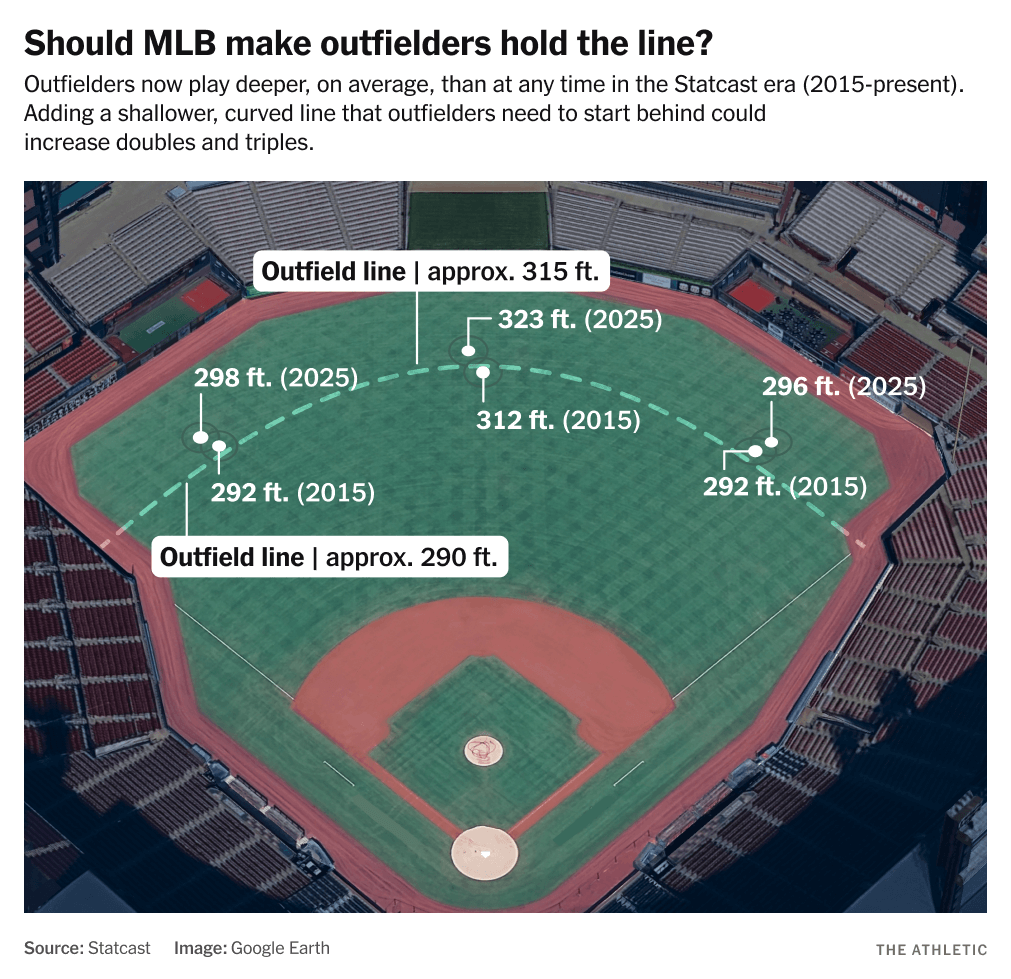

How’s your depth perception? We ask because, thanks to the miracle of Statcast, we can now measure the depth of where every outfielder stands before a ball is hit. And that’s where this conversation has to begin:

The average outfielder now plays deeper than at any time since Statcast has been keeping track (2015-present) — and, most likely, any time in history.

Average outfield depth by position

YEARCFLF RF

2025

323 feet

298 feet

295 feet

2015

312 feet

292 feet

292 feet

(Source: Baseball Savant / Statcast; MLB calculates the starting distance based on how far from the plate the outfielders are when the pitch is released. This is measured before every pitch using Hawk-Eye technology.)

So why is that happening? Because it works! As far back as April 2022, former Cubs/Red Sox mastermind Theo Epstein explained it all perfectly in an appearance on the Starkville edition of The Athletic’s “Windup” podcast, with me and my co-host, Doug Glanville.

“The problem we’re trying to potentially solve here is that analytics have shown clubs that positioning outfielders deeper is a very effective way to prevent runs,” said Epstein, who was then working as a “let’s-fix-the-game” consultant for MLB. “Analytics can really demonstrate that when you move outfielders back, you take away doubles. Sure, you give up a few more singles. But you take away doubles and triples. You turn those extra-base hits into outs. And on average, you’re going to prevent a lot more runs doing it that way.”

There was a time when teams thought the opposite. As recently as the turn of this century, many of them played their athletic center fielders shallow, trying to turn singles into outs.

We’re sure that made sense to somebody back then. But as baseball became more scientific, the data flipped that trend upside-down.

“It’s smart,” Pasquantino said. “It’s like, I’ve seen some theories on the 3-point shot in the NBA, where teams are so smart now. It’s not ruining the NBA by any means. It’s just a math equation. It’s like, why shoot a 17-foot shot when you can shoot a 22-foot shot? It’s not that much different, and it’s worth one more point. So we’ll take the chance that you’ll make maybe a little less of those shots.

“In our sport, they’re saying: ‘Hit your singles,’ (because) how many times do I score when I get to first base, as opposed to when I get to second or third — or just hit a homer? Not often, in comparison. That’s just math.”

Oh, it’s excellent math, all right — but not only for your cousin Vinnie. For everybody.

According to FanGraphs’ Run Expectancy Matrix, when a team puts a runner on second with nobody out, its run expectancy for that inning is 29 percent higher than when that runner is on first with no outs. And with two outs, run expectancy is 48 percent higher.

So it’s not just math. It’s monster math. And all 30 teams are now crushing it. But at this point, it isn’t even new math anymore. So the best and smartest teams are now layering even more levels on top of those deep thoughts. Which is one more powerful example of how …

The defense never rests

“Defensive positioning,” Vinnie Pasquantino said, “is all about: ‘We’re going to take away what you do well.’” (Ed Zurga / Getty Images)

As several people I talked to for this story mentioned, those outfielders didn’t just start playing deeper this year. In fact, they’ve been playing at pretty much the current depths since 2019.

So depth is still a thing, but it’s not the only thing. There is now a precision to defensive positioning that would boggle the mind of the average fan.

Why do outfielders consult the index card inside their cap before every hitter? Not because they have lousy memories. It’s because there are now so many variables, who could possibly keep track of them all?

Here is just a sampling, courtesy of some of the players, coaches and front-office minds I spoke with:

• It’s no longer simply about where each hitter tends to hit the ball. It’s where he tends to hit the ball hardest. Turning those 100 mph laser beams into outs is every team’s top defensive priority these days.

“Defensive positioning,” Pasquantino said, “is all about: ‘We’re going to take away what you do well.’ Where you hit the ball hard, we’re going to play you there. So it’s no secret, when you line out hard somewhere, why you find yourself consistently doing it. It’s because they’re playing you there.”

• But even the same hitter might face different positioning — possibly every at-bat, sometimes even every pitch. Is the next pitch going to be inside or outside, high or low, hard or soft? Is it a pitch you tend to make hard or soft contact on? Is it a pitch you’re likely to try to take the other way? It all matters.

• Then there’s this: Who’s pitching? Is he left-handed or right-handed? But that’s only the first question. Let’s take the Dodgers. Blake Snell, Clayton Kershaw and Alex Vesia all throw left-handed. Is there anything else about them that’s similar? So no outfielder is just playing in the same spot every inning because “a left-hander” is on the mound. It’s about what kind of left-hander is delivering each pitch.

• Then again, not all outfielders are created equal, either. So there’s a huge difference in positioning — on the same hitter — if Nick Castellanos is playing right field, as opposed to, say, a Gold Glover like Fernando Tatis Jr. The data on each outfielder’s range and skills now plays a pivotal role in where he’s standing, for every pitch of every game. And the spacing between outfielders is also part of that sports science.

“Teams are so much more familiar with the skills of their outfielders,” said one coach who has input on his team’s defensive alignments. “So they’re positioning more thoughtfully, relative to the directions the outfielders can go.

“An average outfielder, his catch radius is not a perfect circle, right? And then two outfielders, their average radius is different from each other. So when you have both of those things in mind … you can more thoughtfully place them in space, without the assumption that they’re going to cover the same amount of ground as your average person. Outfielders are more athletic than their predecessors, but we’re also more aware of where their deficiencies live.”

• Not to mention there’s a reason those outfielders seem to be so much more athletic nowadays: Because, now that teams can measure the impact of that athleticism, many of them value outfield defense in ways they’d never valued it before.

The result: The average outfielder in 2025 was significantly faster (27.3 feet per second) than when Statcast began computing that in 2015 (26.9). And while 18 qualified outfielders were 2 feet worse than average, by Statcast’s Outfield Jump metric, in 2016, just seven outfielders were that bad in 2025, as this graphic, from The Athletic’s Eno Sarris, depicts.

(This graphic shows Statcast’s Outfield Jump metric, which combines an outfielder’s reaction, burst and route in the correct direction of a fly ball and compares it to the average. In the top left corner are the outfielders who are below average in both route and reaction, and in 2016 [blue points], you’ll notice there were more bad outfielders.)

• Finally, there’s more nuance to the data on hitters than ever before. So teams are no longer just looking at where, say, Bo Bichette has tended to hit a high fastball in his career, or even this season. That info is now broken down to: What are his tendencies over the last two months … or two weeks … or two series?

OK, so now that we’ve probably overwhelmed you with all that context, you’re no doubt wondering:

What does all that have to do with the secret plot to kill the gapper?

“What outfield positioning has changed,” said the coach quoted earlier, “is … people’s proximity to where the ball lands — not only on balls that are caught, but on balls that aren’t caught. You’re not as far from them as you once were.

“So when you catch them, that prospective double or triple becomes an out. And when you don’t catch them, a prospective triple stays a double, and a potential double becomes a single.”

Got it? Excellent. So …

Why should anybody even care?

“Is there a way to create an outfield-positioning rule that could help nudge the doubles and triples rate, the extra-base hit rate, back to, say, levels where they were 15 years ago or so?” Theo Epstein asked. (Michael M. Santiago / Getty Images)

Nobody wants to root against progress. It’s never a good look. But is it sometimes a necessary look? It is in this sport.

That’s because the people who run baseball teams in 2025 are way too smart. They know exactly how to apply their favorite algorithm to alter that game you just plunked down 78 bucks to watch. And good for them.

But sometimes, the people who run a sport have to ask: What’s more important — brilliant algorithm application or giving ticket buyers something that might be way more entertaining to watch?

Hmmm. What do you think?

While you ponder that, why don’t we revisit how Epstein described this thorny dilemma in his Starkville appearance in 2022. The question on the table was: Why should the league care where teams tell outfielders to stand? This sums it up!

“The reason why that’s a problem in the big picture,” Epstein said, “is that fans tell us they love doubles, they love triples and the action that those plays create. And they love great defensive plays.

“So one thing fans love is when there’s a deep fly ball hit into the gap. The center fielder is at a full sprint going for it. Does he leave his feet and dive? Does he make that play? Or is it going to be a double or triple, base runners in motion, defenses making the relay, bang-bang play at the bag. It’s just a great baseball play.

“And I think what it tells us is that, when the ball is put in play, when the ball’s in the air, I think fans like some element of some suspense, some uncertainty, some action when the ball is hit. And with outfielders playing so deep, when a ball goes up in the air now, it’s oftentimes either a home run or it’s an out.

“So what we’re trying to solve for is, is there a way to create an outfield-positioning rule that could help nudge the doubles and triples rate, the extra-base hit rate, back to, say, levels where they were 15 years ago or so?”

The league is still years away from creating a rule like that. But has it kicked around that question? Oh, yeah. And it isn’t just about the demise of the double and triple. It’s about the toll outfield defense and positioning are taking on offense, period.

I used Statcast to look at what happens these days on hard-hit line drives to deep center field. I chose center field because that’s where we find the biggest change in how deep outfielders play. Ready? These are the numbers on barreled line drives, with exit velocities of 95 mph or harder.

Batting average — In 2016, the league hit .541 on balls hit like that. In 2025, that average had dropped … by 138 points — to .403.

Slugging — But here’s where that outfield positioning really shows up. In 2016, league-wide slugging percentage on those balls was 1.091. By this year, that slugging rate had tumbled … by 300 points — to .791.

So those great baseball plays Epstein described may not feel like they were all part of baseball’s ancient history. But here’s a great example of why they’re becoming increasingly rare.

The center fielder who caught that shot, the A’s Lawrence Butler, wasn’t quite playing with his back up against the Green Monster. But he was playing two steps in front of the warning track. So no wonder the hitter who hit that ball, Alex Bregman, didn’t hesitate when I asked him if he’d be in favor of a limit on where outfielders can stand.

“As a hitter,” he said, instantaneously, “I would love that.”

THE ATHLETIC: “You’d even be OK with painting little circles in the outfield?

BREGMAN: “That would be great — because WE’RE hitting.”

But is that where we’re headed — for little circles on the outfield grass? Probably not. So, let’s consider …

What are the options?

I texted an American League front-office executive recently to tell him I was working on this story, then said (innocently): I’d love to hear your thoughts on this.

His (not serious) reply: “I think we should tell the outfielders they can only jog after the ball.”

OK, that turned out not to be what he actually thought.

“I don’t really think I want to watch a bunch of outfielders standing among a bunch of grid lines in the outfield that looks like a USA Today pie chart,” he said, in a later phone conversation. “But if we find a way to do it without the aesthetics of a bunch of lines written in the outfield, I don’t know that I have a huge problem with it.”

So is it possible to limit where outfielders can stand without painting a dozen chalk lines and circles all over the outfield grass? Am I authorized to speak for the entire planet when I say: Geez, I hope so?

Remember, the league — and baseball’s competition committee — haven’t concluded that they need a rule like this. But if it gets to that point, the beloved, time-honored look of a big-league baseball field would, and should, be part of that conversation.

“In the infield, we have natural boundaries,” the same exec said. “The grass versus the dirt, and the second-base bag. So if we could find a way to do it similarly in the outfield, it’s fine. It doesn’t really bother me.”

A National League exec had a similar reaction.

“I would be open to it,” he said. “The reason I was in favor of (shift limits) in the infield is, I thought it was allowing teams … to play these non-athletic players in the middle of the field at what should be the most athletic positions. I think it starts to take away from the entertainment value for our fans.”

So if entertainment value is goal No. 1, what are the options? The argument for some sort of circles is that they would place more specific limits on where outfielders could play — how deep, how shallow, how close to the lines and/or the gaps. But if we’re not going to dump white chalk all over the field, how would that work?

Could we somehow draw ever-shifting circles with lasers that would create cool colored orbs in the grass? Technologically possible, but way too complicated.

So what about the idea laid out by Epstein in 2022? What about that line cut into the grass that we referred to earlier as the “This Is How We’re Saving the Doubles and Triples Line”?

“Imagine there was a curved line in the outfield,” Epstein said, “and the outfielders just couldn’t start deeper than that line. So more balls are going to be going over their heads. They’re going to have to go back on balls more often. It creates more suspense when balls go in the air. It creates more uncertainty on outcomes, more action, more premium on athleticism in the outfielders.”

Oh, and one more thing. For every 10 feet shallower that outfielders would have to play, Epstein said, the data indicates there would be a 0.2-percentage-point uptick in the rate of doubles and triples — which at least would get the sport closer to its level from more action-packed times.

“So it’s just an interesting concept,” Epstein concluded, “to think about whether it’s worth considering that type of rule, that forces outfielders to start 5 or 10 or 15 feet shallower than the major-league average now — and create a lot more action on balls that go in the air.”

MLB was curious enough that it experimented with that line in 2022, in extended spring training in Arizona. But that was simply to get a feel for how it looked. So what has happened on that front since? Not a thing.

Despite all the back-channel conversation about extending that experiment to a tryout in a minor league or independent league, that hasn’t happened. And it appears that, aside from the automated ball-strike challenge system (ABS) that arrives next year, the league is putting virtually all its potential rule-change plans on the back burner until it gets through the looming labor talks next winter.

But at some point, there will be life after collective bargaining negotiations. So could a save-the-gapper rule then become the rule-change flavor that sweeps across our continent? Surprisingly, not even all the hitters I surveyed are sure they want this.

THE PADRES’ JAKE CRONENWORTH: “I think we’ve already changed so much that we probably shouldn’t change anything else.”

THE CARDINALS’ BRENDAN DONOVAN: “Obviously, extra-base hits are extremely important. But I don’t want to tamper with the game. Teams have to do a good job of game-planning, to make sure that we’re not getting on base. So I think it’s up to us as hitters to try to find a way to make adjustments.”

THE GUARDIANS’ STEVEN KWAN: “I mean, I understand where people are coming from. But I think, as a hitter, you should be rewarded for being a well-rounded hitter. … And as an outfielder, you could definitely show off your athleticism more (if outfielders couldn’t play as deep). But I think I like the positioning, where we’re at right now.”

Freddie Freeman, owner of 547 career doubles, believes players would adjust to a rule change that dictated outfield positioning. (Michael Reaves / Getty Images)

So why is baseball still spinning its wheels on this front? Because even the players it would help most — the hitters — aren’t certain what the answer is. But then there’s Freddie Freeman, who always seems to see the big picture.

“I’m a hitter, so I’m gonna say, yeah, I want more hits,” he said with a laugh.

But then he took a step back to reflect on all the rule changes he and his fellow players have learned to live with through the years. Were they beloved among players on Day 1? Of course not. Freeman pointed to the pitch clock and shook his head.

“So much pushback,” he said. “But now, I think we can all attest that two-hour-and-25-minute games are better, not only for us being on our feet so much, but the fans stay the whole game now.

“So rules are hard to get used to when they come in and you’re so used to something else for so long. But as an industry, we adjust to it. That’s what players do.”

It’s also what leagues do — in every sport — when they see an opening to make their sport more entertaining. And if this league is thinking clearly, how can it not see that this is one of those openings?

One of the coolest parts of modern baseball is the warp-speed innovations and deep thinking inside the game. But as I’ve written here before, there’s a fundamental principle that the powers that be should always keep in mind:

What makes for great baseball strategy doesn’t always make for great entertainment strategy!

And this is one more example. So is it time to revive the double, rescue the triple and save the good old-fashioned gapper? The numbers tell us it’s an idea worth pondering.

“So maybe down the line, that (experiment) could be something that you take to the Atlantic League or you even take to the lower levels of the minor leagues,” Epstein said in 2022, “because for all the talk about infield defense restrictions, I think you actually would get a greater impact on batting average on balls in play, and increase action in the game more, if you could find just the right tweak to outfield positioning — and really bring back a lot of action and drama on balls and plays in the outfield.”

— The Athletic’s Eno Sarris contributed to this report.