I sometimes can’t remember things my wife told me 10 minutes ago, but I distinctly recall a conversation I had with my friend, the late Joe Strauss, after the baseball writers elected Kirby Puckett to the Hall of Fame in 2001.

By then, Joe and I were no longer colleagues at the Baltimore Sun, but we still spoke frequently. Joe, never shy about his opinions, often dispensing them like blunt-force objects, said flatly, “Electing Puckett was a big mistake.”

Puckett’s 12-year career ended prematurely when glaucoma caused him to lose vision in his right eye. He did not play long enough to approach widely accepted Hall standards of 500 homers and 3,000 hits. Joe feared that by electing Puckett, the writers were establishing a dangerous precedent, in effect creating arguments for other players with shorter peaks.

Nearly a quarter-century later, those arguments are becoming more pointed. Certain players, particularly pitchers, do not last as long as they once did, and as performance standards change, voters must recalibrate as well.

The writers should perhaps take a kinder view of candidates such as Félix Hernández, Chase Utley, Dustin Pedroia and David Wright. Ditto for the Contemporary Era Committee, which will vote Sunday on Don Mattingly and Dale Murphy, two players with careers comparable to Puckett, along with six others: Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Carlos Delgado, Jeff Kent, Gary Sheffield and Fernando Valenzuela.

Puckett, to me, was a singular player as a dynamic hitter, a two-time World Series champion and a six-time Gold Glove winner at center field, one of the game’s most important defensive positions. He also had a charismatic personality and a fire hydrant build, both of which endeared him to fans.

My support for Puckett, though, went against my usual tendencies. Generally, I prefer volume when voting for individual awards and the Hall of Fame, leaning toward pitchers with high innings totals in Cy Young balloting and favoring hitters with 10 years of dominance for Cooperstown. Looking back on it, though, Puckett’s election wasn’t a mistake. If anything, the writers might have been ahead of their time.

The game has evolved. The 300-win standard for pitchers, flawed as it might have been, is no longer an appropriate measure. Justin Verlander, the active leader with 266 wins, will be 43 in February. Max Scherzer, 41, is the only other pitcher above 153.

Starting pitching’s diminishment is one thing. Physical issues also lead some players into early retirement. When Buster Posey becomes eligible for the Hall next year, he likely will be elected with 1,500 hits — exactly half of what was once considered the minimum necessary for admission.

The decisions by the Contemporary Era Committee, composed of 16 Hall of Fame members, major-league executives and veteran reporters/historians, including The Athletic’s Jayson Stark and Tyler Kepner, will not necessarily influence trends in future writers’ votes. Still, Mattingly and Murphy, in particular, are fascinating test cases.

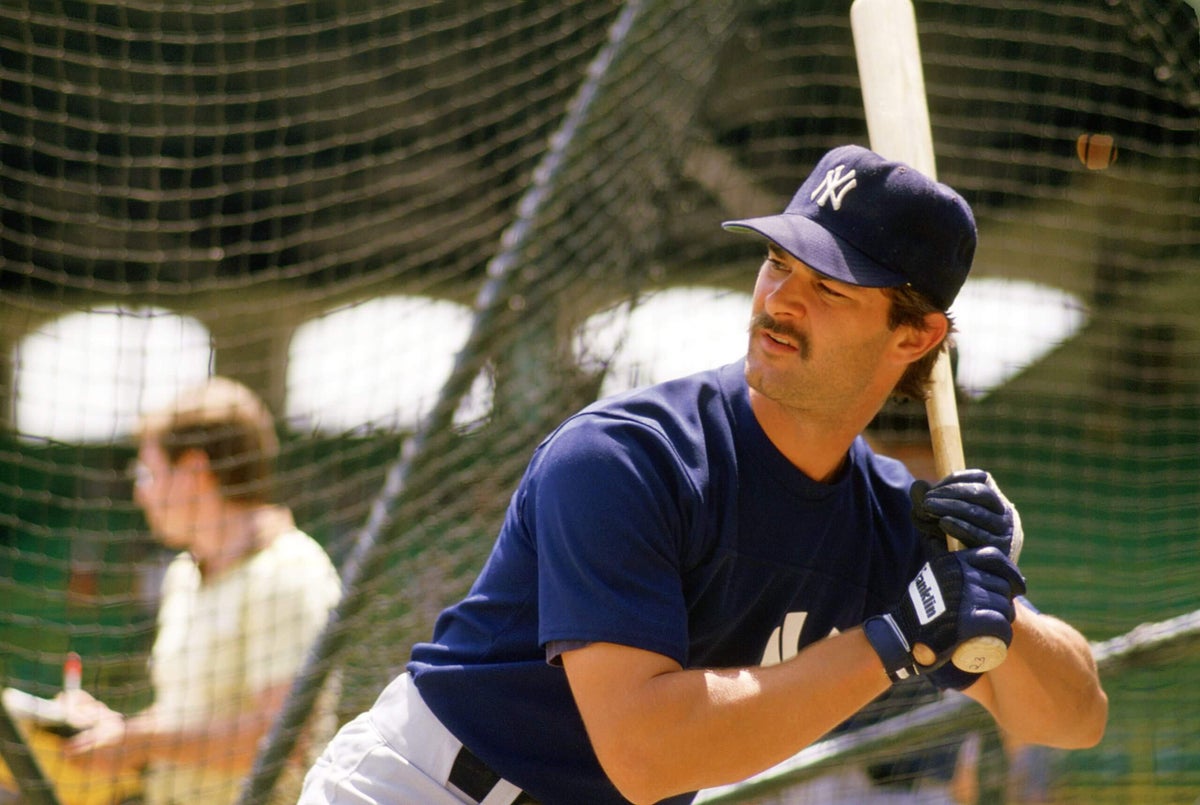

Mattingly’s career numbers, in everything from games played to batting average to home runs, were quite similar to Puckett’s. OPS wasn’t a thing then, nor was OPS-plus, but those stats, once they came into vogue, turned out to be pretty close, too.

So, why was Puckett elected on the first ballot while Mattingly received only 28.2 percent of the vote in his debut that same year, his high-water mark in 15 years on the writers’ ballot?

My friend Joe contended, not unreasonably, that Puckett’s election was something of a sympathy vote. Mattingly stopped playing because of a congenital back condition, a less sudden and dramatic ailment than Puckett’s eye trouble. He played his last season at 34, Puckett at 35.

True, Puckett played center field, a more valuable defensive position than first base, and won two World Series to Mattingly’s none. His final 10 seasons amounted to his peak, while Mattingly’s lasted perhaps only six. The difference between them, though, wasn’t as vast as the balloting reflected.

Murphy fared even worse than Mattingly among the writers, topping out at 23.2 percent. Like Puckett, Murphy spent the majority of his career in center field, winning five Gold Gloves. Like Mattingly, Murphy for a time was considered perhaps the best player in the game, receiving MVP votes in seven of eight seasons between 1980 and 1987, and winning the award twice. After his age-31 season, however, he was essentially a league-average hitter.

Both Mattingly and Murphy on Sunday will make their 19th appearances on a Cooperstown ballot, the most of the eight players up for election. Starting in 2015, the Hall of Fame reduced a player’s maximum eligibility from 15 years to 10. This is the fourth time Mattingly and Murphy have drawn consideration from an Eras Committee.

Difficult as it is to imagine either of them going 0-for-19 in anything, Mattingly and Murphy will need to receive 12 of 16 votes for election, and they are on a packed ballot. Voters are instructed to consider “contributions to the game,” which should help Mattingly, who has also spent more than two decades as a coach and manager. If the electors hold Bonds’ and Clemens’ alleged uses of performance-enhancing drugs against them, shouldn’t they factor in the positive impact of those lauded for their character?

The same question, of course, applies to the writers, or should have, when those players were eligible. Mattingly and Murphy were considered shining representatives of the sport, as were Delgado and Valenzuela. Murphy and Delgado both won Roberto Clemente Awards. Puckett did, too.

Former Braves star Dale Murphy throws the ceremonial first pitch before Game 2 of the NLCS in Atlanta in 2021. (Kevin C. Cox / Getty Images)

(For the record, I began voting for both Bonds and Clemens in their third year of eligibility in 2015, no longer willing to exclude them when I believed we already had elected others who had used performance-enhancing drugs. I do not vote for players such as Alex Rodríguez and Manny Ramírez, who violated baseball’s drug policies after the league and union established firm rules. But back to the current discussion!)

The Contemporary Era Committee’s election of a high-peak candidate such as Mattingly, Murphy or Valenzuela would not necessarily influence the writers, who are largely a different bloc of voters. However, if the writers elect Posey next year — and it will be difficult to ignore a catcher who was the centerpiece of three World Series champions with one franchise — it could provide a significant boost to Pedroia, Wright and similar types.

Posey’s 1,500 hits would not be the lowest total by a Hall of Fame position player who played in the American and/or National Leagues, but it would be the fewest by a BBWAA inductee since Ralph Kiner in 1975. In the 50 years since, the writers have not elected any player with fewer than 2,000 hits.

Utley, who had 1,885 hits, is already testing that standard. He received 28.8 percent and 39.8 percent of the vote in his first two years on the ballot, gaining momentum toward the minimum 75 percent required. Wright (1,777 hits) has also been on the ballot for two years, going from 6.2 percent to 8.1 percent. Pedroia (1,805) tallied 11.9 percent of the vote in his first year on the ballot.

All three players dealt with major physical issues, raising the question: How much should injuries factor into a Hall of Fame candidate’s chances?

On one hand, voters should judge only what a player accomplished, not what might have been. On the other hand, should Utley be penalized for his knee troubles? Wright for his career-ending spinal stenosis? Pedroia for the knee problems that began after Manny Machado slid into his left knee, leading to multiple surgeries and forcing him into early retirement?

Electing such players might amount to a slippery slope, harkening back to my friend Joe’s concerns when we elected Puckett. Voters will need to decide which players were truly outliers. The beauty of the process is that everyone will form their own opinions.

Among pitchers, Sandy Koufax was the ultimate example of an outlier; his five-year peak was so brilliant, writers elected him on the first ballot. Hernández wasn’t at Koufax’s level, but over a seven-year span, he earned six top-10 Cy Young finishes, including one first, two seconds and a fourth. He faded rapidly, in part, perhaps, because the Seattle Mariners pushed him hard at a young age.

As always with the Hall of Fame, there are no easy answers, just debates full of comparisons and often contradictions. Only one thing is certain, no matter who the Contemporary Era Committee elects on Sunday. Both committee members and writers need to weigh candidates differently than in the past. As the game evolves, the criteria for election need to evolve, too.