Jerry Lai-USA TODAY Sports

Jerry Lai-USA TODAY Sports

The following article is part of Jay Jaffe’s ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2026 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to this year’s ballot, and other candidates in the series, use the tool above; an introduction to JAWS can be found here. For a tentative schedule and a chance to fill out a Hall of Fame ballot for our crowdsourcing project, see here. All WAR figures refer to the Baseball Reference version unless otherwise indicated.

In an age when baseball is so obsessed with velocity, it’s remarkable to remember how recently it was that a pitcher could thrive, year in and year out, despite averaging in the 85–87 mph range with his fastball. Yet that’s exactly what Mark Buehrle did over the course of his 16-year career. Listed at 6-foot-2 and 240 pounds, the burly Buehrle was the epitome of the crafty lefty, an ultra-durable workhorse who didn’t dominate but who worked quickly, used a variety of pitches — four-seamer, sinker, cutter, curve, changeup — moving a variety of directions to pound the strike zone, and relied on his fielders to make the plays behind him. From 2001 to ’14, he annually reached the 30-start and 200-inning plateaus, and he barely missed on the latter front in his final season.

August Fagerstrom summed up Buehrle so well in his 2016 appreciation that I can’t resist sharing a good chunk of it:

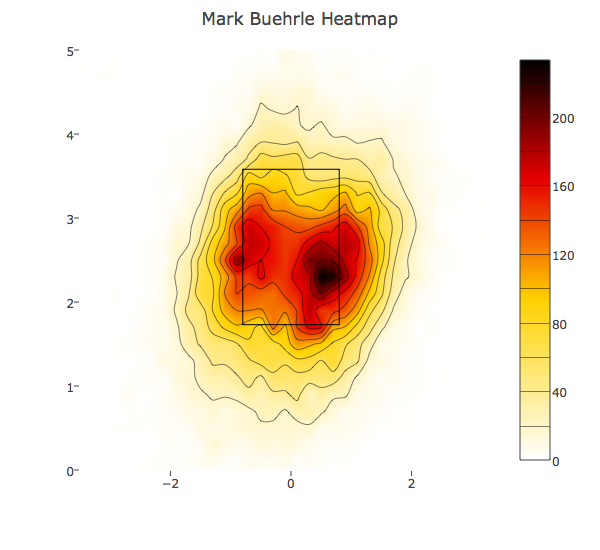

The way Buehrle succeeded was unique, of course. He got his ground balls, but he wasn’t the best at getting ground balls. He limited walks, but he wasn’t the best a limiting walks. He generated soft contact, but he wasn’t the best at generating soft contact. Buehrle simply avoided damage with his sub-90 mph fastball by throwing strikes while simultaneously avoiding the middle of the plate:

That’s Buehrle’s entire career during the PITCHf/x era, and it’s something of a remarkable graphic. You see Buehrle living on the first-base edge of the zone, making sure to keep his pitches low, while also being able to spot the same pitch on the opposite side of the zone, for the most part avoiding the heart of the plate. Buehrle’s retained the ability to pitch this way until the end; just last year [2015], he led all of baseball in the percentage of pitches located on the horizontal edges of the plate.

Drafted and developed by the White Sox — practically plucked from obscurity, at that — Buehrle spent 12 of his 16 seasons on the South Side, making four All-Star teams and helping Chicago to three postseason appearances, including its 2005 World Series win, which broke the franchise’s 88-year championship drought. While with the White Sox, he became just the second pitcher in franchise history to throw multiple no-hitters, first doing so in 2007 against the Rangers and then adding a perfect game in ’09 against the Rays. After his time in Chicago, he spent a sour season with the newly rebranded Miami Marlins, and when that predictably melted down, spent three years with the Blue Jays, earning one more All-Star nod and helping them make the playoffs for the first time in 22 years.

Though Buehrle reached the 200-win plateau in his final season, he was just 36 years old when he hung up his spikes, preventing him from more fully padding his counting stats or framing his case for Cooperstown in the best light. A closer look beyond the superficial numbers suggests that, while he’s the equal or better of several enshrined pitchers according to WAR and JAWS, he’s far off the standards. Like fellow lefty and ballot-mate Andy Pettitte, he gets a boost from S-JAWS, a workload-adjusted version of starting pitcher JAWS that I introduced in 2022. Thus far, I’ve only included Pettitte on one of my five ballots (one of seven including virtual ballots), though I’m mulling his inclusion this year — a thought process that’s taking place as the electorate grapples with shifting standards for starting pitchers following last year’s election of CC Sabathia and the candidacies of Félix Hernández (who debuted last year) and Cole Hamels (this ballot’s top newcomer). I’ve pledged to reconsider Buehrle as well; I’m 0-for-5 in voting for him thus far, and I’m hardly alone, as he debuted with 11% in 2021, scraped by with 5.8% the next year, and has barely regained that lost ground, receiving 11.4% in 2025.

A note about pitcher wins: Regular readers know that I generally avoid dwelling on the stat, because in this increasingly specialized era, they owe as much to adequate offensive, defensive, and bullpen support as they do to a pitcher’s own performance. While one needn’t know how many wins Buehrle amassed in a season or over his career to appreciate his true value, those totals have affected the popular perception of his career.

2026 BBWAA Candidate: Mark Buehrle

Pitcher

Career WAR

Peak WAR Adj.

S-JAWS

Mark Buehrle

59.1

35.8

47.4

Avg. HOF SP

72.9

40.7

56.8

214-160

1,870

3.81

117

SOURCE: Baseball Reference

Mark Alan Buehrle was born on March 23, 1979 in St. Charles, Missouri, a northwest suburb of St. Louis. He was the youngest son out of the four children of John and Pat Buehrle. His father worked as a paramedic for 15 years, then managed St. Charles’ water systems; he also served as scoutmaster and Little League coach for his boys.

Even as a toddler, Mark impressed people with his arm, dominating bean bag tosses at school picnics. “He was two years old and everyone thought he was a ringer,” John told Sportsnet’s Michael Grange in 2014. “We’d have an arm full of stuffed toys and they’d tell us to go rob someone else.”

When Mark was six or seven, a fellow Little League coach advised his father to get some more expert instruction for his son. At a baseball clinic in St. Louis, former Cardinals pitcher and 1983 Cy Young winner John Denny recognized the young Buehrle’s talent and asked to work with him; the pair worked together until Buehrle was 13 or 14. Even so, he was cut from his freshman and sophomore teams at Francis Howell North High School, though he continued to play summer ball. After a growth spurt and advice from his parents to give it one more shot, he made the varsity team as a junior.

You Aren’t a FanGraphs Member

It looks like you aren’t yet a FanGraphs Member (or aren’t logged in). We aren’t mad, just disappointed.

We get it. You want to read this article. But before we let you get back to it, we’d like to point out a few of the good reasons why you should become a Member.

1. Ad Free viewing! We won’t bug you with this ad, or any other.

2. Unlimited articles! Non-Members only get to read 10 free articles a month. Members never get cut off.

3. Dark mode and Classic mode!

4. Custom player page dashboards! Choose the player cards you want, in the order you want them.

5. One-click data exports! Export our projections and leaderboards for your personal projects.

6. Remove the photos on the home page! (Honestly, this doesn’t sound so great to us, but some people wanted it, and we like to give our Members what they want.)

7. Even more Steamer projections! We have handedness, percentile, and context neutral projections available for Members only.

8. Get FanGraphs Walk-Off, a customized year end review! Find out exactly how you used FanGraphs this year, and how that compares to other Members. Don’t be a victim of FOMO.

9. A weekly mailbag column, exclusively for Members.

10. Help support FanGraphs and our entire staff! Our Members provide us with critical resources to improve the site and deliver new features!

We hope you’ll consider a Membership today, for yourself or as a gift! And we realize this has been an awfully long sales pitch, so we’ve also removed all the other ads in this article. We didn’t want to overdo it.

Though lacking in velocity, Buehrle’s ability to throw strikes with consistency led to his being recruited by Jefferson Community College, 45 minutes south of St. Charles, where he received a full scholarship. Offsetting a fastball that maxed out at 88 mph with a cutter, curve, and changeup, Buehrle went 7–0 as a freshman in 1998. The White Sox chose him in the 38th round as a draft-and-follow, meaning that the team retained his rights until a week before the next year’s draft. White Sox area scout Nathan Durst had liked his initial view of Buehrle, telling The Athletic’s James Fegan in 2020 that what stood out was the lefty’s “complete lack of fear, and always throwing to the glove regardless of what happened the previous pitch or the previous [at-bat]… The velo is just not there, but he can really pitch. He pours it in the strike zone. Everything works. Arm works, control, spins it, feel for secondaries, but the power just isn’t there.”

After going 8–4 with a 1.45 ERA as a sophomore, Buehrle signed for a $150,000 bonus from the White Sox in May 1999 and quickly moved on to the Low-A Midwest League, where he went 7–4 with a 4.10 ERA and 8.3 strikeouts per nine. He put in a strong 16-start stint at Double-A Burlington the following year, highlighted by a 2.28 ERA. Less than a week after striking out two and collecting the win for the U.S. Team in the All-Star Futures Game, the 21-year-old southpaw made his major league debut, allowing a run in an inning of garbage time relief against the Brewers on July 16; José Hernández was his first strikeout victim. Three days later, he replaced the injured Cal Eldred in the White Sox rotation and spun seven innings of two-run ball against the Twins in his first start, striking out five and collecting his first win.

Eldred’s elbow injury proved season-ending, but Buehrle made only two more starts, with diminishing returns, before returning to the bullpen. He pitched to a 4.21 ERA and 4.28 FIP in 28 appearances totaling 51 1/3 innings of mostly low-leverage work for a team that won 95 games and the AL Central. Included on the playoff roster for the Division Series against the Mariners, he made one mop-up appearance, allowing back-to-back singles to Raúl Ibañez and Mike Cameron before striking out Alex Rodriguez. The White Sox, however, were swept.

The 22-year-old Buehrle made the White Sox rotation out of spring training in 2001, and while he was shaky in the early going, allowing five or more runs in four of his first six starts, he pitched a three-hit shutout against the Tigers, kicking off a streak of 24 2/3 consecutive scoreless innings, and finished the year 16–8 with a 3.29 ERA (fourth in the league, and good for a 140 ERA+) and 6.0 WAR (third) in 221 1/3 innings. His string of 14 straight seasons topping 200 frames was underway. The Sox, however, sank to 83 wins, and won only 81 games in 2002, but in the latter year, Buehrle made his first All-Star team, and his 239 innings fell one out short of matching Roy Halladay for the league lead. He could have snared the lead and secured his 20th victory if not for a home run by the Twins’ Bobby Kielty in the eighth inning of his final start on the penultimate day of the season, turning a 2–1 lead into a 3–2 deficit. As it was, he finished 19–12 with a 3.58 ERA (126 ERA+) and 5.0 WAR (eighth in the league).

Judged by ERAs, Buehrle’s 2003 and ’04 seasons (4.14 and 3.89, respectively) weren’t quite up to the standards of his first two as a starter, though he totaled a respectable 6.7 WAR in 475 2/3 innings and bought himself some security in the form of a three-year, $18 million extension with a club option for 2007. What’s interesting to note about his up-and-down performances is that by FanGraphs’ version of WAR, his 2001–04 seasons — which featured single-season ERAs that differed from best to worst by 0.85 runs per nine and Baseball Reference WAR totals that ranged from 2.5 to 6.0 — were virtually identical, with his WAR totals falling in the 4.0–4.5 range and FIP- figures ranging from 87 all the way to… 89. Meanwhile, his BABIPs ranged from .242 in 2001 to .296 in ’03.

Here it’s important to note that on a career-long basis, B-Ref’s version of WAR works in Buehrle’s favor by rewarding him for out-pitching his peripherals (3.81 ERA, 4.11 FIP) through some combination of contact suppression and sequencing. On the latter front, he often drew comparisons to Hall of Famer Tom Glavine, whose career 3.54 ERA far outdistanced his 3.95 FIP. Buehrle’s 59.1 bWAR (including offense) is about 15% higher than his 51.5 fWAR.

By significantly trimming his home run rate, Buehrle posted career bests in both ERA and FIP (3.12 and 3.42, respectively) in 2005, heading a rotation that included three other hurlers (Freddy Garcia, Jon Garland, and José Contreras) who like him each reached the 32-start/200-inning thresholds. After three straight second-place finishes in the AL Central, including an 83–79 campaign under first-year manager Ozzie Guillen in 2004, the White Sox improved to 99–63 and won the AL Central. Buehrle led the AL with 236 2/3 innings (he’d done so the year before as well), made his second All-Star team, and totaled 4.8 WAR. For the only time in his career, he received mention in the Cy Young voting, though he still finished fifth; Bartolo Colon won.

Buehrle’s postseason performance was uneven, as he sandwiched seven-inning, four-run performances in the Division Series against the defending champion Red Sox and in the World Series against the Astros around a five-hit complete game in the ALCS against the Angels. He got adequate offensive support in all three starts, each of them one-run Game 2 wins by the White Sox; the ALCS win came on a walk-off double by Joe Crede.

Buehrle made a cameo in the 14th inning of Game 3 of the World Series, after the White Sox scored two runs to take a 7–5 lead. With two outs and runners on the corners, he relieved Damaso Marte and induced Adam Everett to pop out to shortstop Juan Uribe, earning the only save of his major league career. The White Sox would finish their four-game sweep — and 11–1 postseason run — the next night, giving them their first championship since 1917.

The extra innings Buehrle threw in the postseason may have caught up to him in 2006. After finishing June with a 9–4 record and 3.22 ERA (but just a 4.53 FIP), a performance that led to his third All-Star selection, he was torched for a 7.12 ERA the rest of the way, going 3–9 and serving up 24 home runs in 92 1/3 innings during that slog. He skipped his final turn but still finished with 204 innings, albeit with a career-worst 4.99 ERA. Despite his dud of a season, the White Sox picked up his $9.5 million option, but his 2007 season didn’t start well; he took a Ryan Garko line drive off his left forearm in the second inning of his April 5 outing, and had to depart. But on April 18, a chilly night at U.S. Cellular Field, with first-pitch temperatures at 40 degrees, he tossed a no-hitter against the Rangers, with a fifth-inning walk of Sammy Sosa the only blemish.

Though the White Sox went just 72–90, and though Buehrle made just three September starts so that the team could evaluate its younger rotation options, he finished the year with 30 starts, 201 innings, a 3.63 ERA (130 ERA+) and a career-high 6.1 WAR, good for sixth in the league. In July, he signed a four-year, $56 million extension.

With youngsters John Danks and Gavin Floyd coming through in the rotation, and with Buehrle turning in a typical season (15–12, 3.79 ERA, and 4.4 WAR in 218 2/3 innings) highlighted by a 2.29 ERA in September, the White Sox won an AL Central race that needed a Game 163 tiebreaker, which they won 1–0 on Jim Thome’s seventh-inning homer off the Twins’ Nick Blackburn, and eight shutout innings from Danks. Alas, in Game 2 of the Division Series against the Rays, with the White Sox already down 1–0 in the series, Buehrle allowed five runs in seven innings and took the loss; Tampa Bay won the series in four games.

Buehrle’s top highlight in 2009, and perhaps the top highlight of his career, would come against those same Rays. On July 23 at U.S. Cellular, he made history by retiring all 27 Tampa Bay hitters in a row for just the 16th perfect game in modern major league history, but the first of six within a 37-month span. The most dramatic play of the game came with nobody out in the top of the ninth, when center fielder Dewayne Wise, who had just entered the game as a defensive replacement, climbed the wall to rob Gabe Kapler of a home run.

In his next start, Buehrle threw 5 2/3 perfect innings before issuing a walk to Alexi Casilla and then a single to Denard Span. In doing so, he set a major league record by retiring 45 consecutive hitters, surpassing Jim Barr (1972 Giants) and longtime teammate Bobby Jenks (2007 White Sox). The record — eventually broken by Yusmeiro Petit in 2014 — highlighted what turned out to be Buehrle’s fourth All-Star season, and his first of four straight with a Gold Glove. His 5.3 WAR was good for seventh in the AL, though his 4.46 FIP was the second-highest mark of his career.

Buehrle spent two more years in Chicago, turning in two Buehrle-esque seasons that were similar in terms of wins (13 apiece), FIP (3.90 and 3.98), and WAR (3.8 apiece) but divergent in ERAs (4.28 in 2010, 3.59 in ’11) thanks to varying BABIPs (.313 and .294); in the former, he struck out a career-low 11.0% of batters. The White Sox, who had won 79 games in 2009, rebounded to 88 wins and a second-place AL finish in ’10, but fell back to 79 wins in ’11.

Just before the end of the 2011 season, Guillen stepped down as the manager of the White Sox when they wouldn’t offer him an extension. The move allowed him to become the manager of the now-Miami Marlins, who were in the process of a major makeover as they moved into brand new Marlins Park. That the Sox didn’t offer Buehrle an extension before he reached free agency played into the 32-year-old lefty’s decision about his own future. He never did get a formal offer from the White Sox, while the Nationals pursued him on a three-year deal. Ultimately, he reunited with Guillen on a four-year, $58 million deal that was part of a $191 million December spending binge during which the Marlins also signed José Reyes (six years, $106 million) and Heath Bell (three years, $27 million) and reportedly pursued Prince Fielder and Albert Pujols.

Buehrle was as solid as ever in Miami (3.74 ERA and 3.5 WAR, including -0.7 for offense via his inept 3-for-67, 29-strikeout showing at the plate), and despite an 8–14 April, the new-look team climbed into a tie for first place in the NL East on June 3… only to plunge into a 3–17 skid and finish 69–93. Guillen got the axe on October 23, and four weeks later, the Marlins traded Buehrle, Reyes, Josh Johnson, and two other players to Toronto in exchange for a seven-player package. The Marlins justified the deal by pointing to their poor attendance (12th in a 16-team league) in their new ballpark, though the fact that the franchise had burned fans with three previous fire sales shouldn’t be underestimated.

The trade presented a problem for Buehrle, in that he could not take his 65-pound pit bull to Ontario, which had prohibited the dogs; rather than leave his pet in someone else’s care or commute from a municipality that did allow pit bulls (as he had done by living in Florida’s Broward County), he chose to leave his whole family — wife Jamie, two small children, and the dog — in St. Louis for the season. His first year north of the border was nothing to write home about (4.15 ERA, 99 ERA+, 2.3 WAR), as the Blue Jays went 74–88, but thanks to a career-low 0.67 homers per nine in 2014, he made his fifth and final All-Star team, posting his lowest ERA and FIP since 2005 (3.30 and 3.66, respectively) and helping the Blue Jays improve to 83–79. His 202 innings gave him 14 straight seasons at that plateau, a feat matched or bettered by only seven pitchers since 1901 — Warren Spahn (17); Gaylord Perry and Don Sutton (both 15); and Christy Mathewson, Greg Maddux, and Phil Niekro (all 14) — all of whom are Hall of Famers. Cy Young had 19 straight seasons with at least 200 innings spanning from 1891 to 1909.

Buehrle ended the 2014 season with 199 wins, and neither he nor his teammates let the suspense build when it came to the milestone. In his season debut on April 10, 2015 in Baltimore, the Blue Jays spotted him a 4–0 lead before he’d even thrown a pitch, and at one point led 9–1. Buehrle had to grind his way through six innings, retiring the side in order just once but allowing only two runs to get the W.

The Blue Jays hadn’t made the playoffs since winning back-to-back World Series in 1992 and ’93, but Buehrle did his best to help end that drought. He carried a 3.31 ERA into mid-August, but posted a 5.56 ERA over his final nine starts, battling shoulder soreness that necessitated a cortisone shot. With the Blue Jays having clinched the AL East title, he threw 6 2/3 innings and allowed four runs on October 2, their 160th game of the season. Two days later, needing two innings to keep his streak of 200-inning seasons alive and with rumors of his retirement in the air, manager John Gibbons gave Buehrle another turn. Unfortunately, he couldn’t get out of the first inning, allowing five hits and a walk, exacerbated by two errors behind him. He retired just two batters, and was charged with eight runs, all unearned.

What’s more, the Blue Jays bypassed Buehrle for a postseason roster spot, as David Price, Marcus Stroman, Marco Estrada, and R.A. Dickey were all pitching well at that point. “It’s tough, it sucks, but I understand the situation,” he said. “I haven’t been throwing great the last month, and we’ve got four guys who have been throwing the [heck] out of the ball. They’re going to take it and run with it. I’ll be ready if something happens.” While those starters’ postseason performances were uneven, Buehrle did not pitch again. The Blue Jays made it as far as Game 6 of the ALCS before being ousted by the Royals.

A free agent again at age 37, Buehrle received inquiries from at least 10 teams; the Toronto Sun’s Bob Elliot reported that he would either sign with the hometown Cardinals or retire. No deal came to pass, and as of February, he had no plans to sign but had not ruled out a comeback. He remained committed to not pitching, and in February 2017, the White Sox announced they would retire his No. 56 jersey, at which point he said that he had more or less decided that the four-year contract he signed with the Marlins would be his last. “I’ve always told people I was a young guy that came into the big leagues unknown,” he said at the time. “Kind of snuck into the big leagues and I wanted to kind of sneak my way out.”

…

Pitchers who win 200 games have become relatively rare; Buehrle is one of just 26 to debut in the majors since the start of 1984 and reach that milestone, while just two active pitchers, Gerrit Cole (153) and Chris Sale (145) are even within 75 wins of the mark. The fact that Buehrle blew past the milestone while making his last appearance before his 37th birthday invites a closer look, particularly on a ballot where Pettitte and his 256 wins receive enough support to persist as a candidate.

That said, Buehrle doesn’t exactly stand out even within this company. He’s 19th in wins, ahead of Hall of Famers John Smoltz (213) and Halladay (203). He’s tied for 16th with Pettitte and Jon Lester in ERA+ (117), and while the trio are just one point behind Glavine, that’s in about 1,100 fewer innings for Buehrle and Pettitte, and about 1,700 fewer for Lester. Buehrle is dead last in this group in strikeout rate (13.6%) — the only 200-win pitcher from the period besides Kenny Rogers who didn’t reach 2,000 strikeouts, and in Buehrle’s case, that’s while ranking 15th in innings.

Beyond the pitching triple crown stuff, Buehrle is one of 13 pitchers in that 200-win group never to win a Cy Young award. His lone fifth-place finish puts him in the company only of Rogers and ahead of Chuck Finley, whose only Cy Young placement was seventh in 1990. In terms of the Cy Young Shares vs. Most WAR Shares comparison I used for Hamels — I’m going to link you to that one instead of spending a few hundred words re-explaining it — his ratio of 0.04 for the former (even less Cy Young support than Hamels received) to 0.2 for the latter (little presence among the league leaders in WAR, more on which below) isn’t particularly out of balance.

Buehrle’s five All-Star appearances and four Gold Gloves makes for a respectable collection of honors, but modest by Hall standards. Gold Gloves shouldn’t get a pitcher into Cooperstown, anyway (though it seems to have worked for 16-time winner Jim Kaat); whatever fielding prowess they purportedly represent is already incorporated into a pitcher’s run prevention numbers. Via the Bill James Hall of Fame Monitor, which gives credit for things that tend to sway voters such as awards, league leads, postseason performance — not that a 2–1 record with a 4.11 ERA is much help — and so on, he scores just 52, well short of a likely Hall of Famer, and below even Hamels (57) and Hernández (67), two pitchers who fell short of 200 wins.

As for the perfect game and no-hitter, they’re fantastic accomplishments, but by themselves, they’re not indicative of Hall-worthiness. Of the 22 pitchers to throw a perfect game since 1901, only seven are enshrined, including only two of the last 15; a perfect game wasn’t enough to get long-lasting lefties Rogers or David Wells there, either. Likewise when it comes to pitchers with multiple no-hitters; Halladay and Randy Johnson are in, but there are plenty who are not, from Johnny Vander Meer to Hideo Nomo and Tim Lincecum, the two most recent ones to be rejected by Hall voters.

The advanced stats don’t make any stronger a case for Buehrle, who ranked among his league’s top 10 in WAR six times but in the top five just twice, and never higher than third. He topped 5.0 WAR just four times, with a high of 6.1. His 59.0 career WAR is tied with Hamels, Eddie Cicotte, Urban Shocker, and Hall of Famer Joe McGinnity for 69th among starting pitchers, 13.9 below the standard and ahead of just 20 of the 67 non-Negro Leagues enshrinees, only six of whom were elected by the BBWAA. Four of those were elected despite short careers (Dizzy Dean, Catfish Hunter, Sandy Koufax, and Bob Lemon) but had other things going for them, including stellar postseason work and better Hall of Fame Monitor scores. So did the longer-lasting Whitey Ford (whose bWAR is curiously low) and Herb Pennock.

A few years ago, I introduced S-JAWS, a variant of my metric that I designed to reduce the skewing caused by the impact of 19th-century and Deadball-era pitchers, some of whom topped 400, 500, or even 600 innings in a season on multiple occasions, generally under much more pitcher-friendly conditions than hurlers of today enjoy. The way I’ve done this is by prorating the peak-component credit for any heavy-workload season to a maximum of 250 innings, which ends up giving a boost to more recent pitchers by suppressing the peak-score impact of the massive seasons by those ancient hurlers. Like Pettitte, Buehrle never reached 250 innings, so his actual peak score of 35.8 remains unchanged, but his ranking among all starters has jumped from 151st (ahead of just nine enshrinees, including the BBWAA-elected Hunter, Ford, and Sutton) to 98th (ahead of 22 enshrinees).

That adjusted peak score is still 4.9 WAR below the standard, though, and Buehrle’s 47.4 S-JAWS (unchanged from his JAWS) is 9.4 points below the standard; the latter ranks 79th, ahead of 19 non-Negro Leagues Hall of Famers including the BBWAA-elected Ford, Koufax, Dean, Lemon, Pennock, and Hunter. All of those pitchers also have a lot of other things going for their Hall cases; all but Pennock have Hall of Fame Monitor scores of 112 or higher, more than double Buehrle’s 52. Even Pettitte, whose 47.2 S-JAWS is a whisker below Buehrle’s, has a 128 Monitor score thanks in part to his postseason accomplishments. Buehrle just doesn’t belong in this company.

Repeating a variation of the table I’ve run in my other starting pitchers profiles for this ballot, here are the percentile rankings in adjusted peak score and JAWS for those starters, as well as various non-candidates, including 2025 inductee Sabathia.

Starting Pitcher Adjusted Peak and S-JAWS Percentiles

Version

Median

25th

75th

CCS%

JS%

CH%

MB%

AP%

FH%

AW%

Peak Adj. Median

39.4

34.6

48.7

50

77

39

34

20

45

7

S-JAWS Median

53.6

46.2

65.3

39

30

29

28

27

21

12

% headers refer to percentile rankings (relative to the 67 enshrined non-Negro Leagues starters) for the following pitchers: CC Sabathia (CCS%), Johan Santana (JS%), Cole Hamels (CH%), Mark Buehrle (MB%), Andy Pettitte (AP%), Félix Hernández (FH%), and Adam Wainwright (AW%).

Sabathia’s adjusted peak score is right at the median, and his S-JAWS in the 39th percentile. Aside from the still-active Max Scherzer and Justin Verlander and the now-retired Zack Greinke and Clayton Kershaw — all of whom rank among the top 27 in S-JAWS — it’s anyone’s guess as to whether we’ll see anyone on the BBWAA ballot that high again. I’ve included Johan Santana here, a two-time Cy Young winner who went one-and-done on the 2018 ballot and won’t be eligible again until the 2029 Contemporary Baseball Era Committee one (if the format remains unchanged); you can see that not only does he have the best peak of any of these pitchers, but even with far fewer innings, his S-JAWS is superior to those of this ballot’s four starters. I threw in Adam Wainwright, the most recent pitcher to reach 200 wins, who along with Greinke will debut on the 2029 ballot; Lester, who also has 200 wins but ranks slightly below Wainwright in S-JAWS, hits the ballot next year. What’s interesting about Buehrle in this context is that his adjusted peak score, which is roughly equidistant between Hamels (37.4) and Pettitte (34.1), is a lot closer to the former in terms of the percentiles.

Is that enough to offset Pettitte’s advantage when it comes to postseason résumés, to the point that I should vote for (or not vote for) both? I’ve been turning this question over in my mind for weeks already, and I still haven’t figured out where I’ll land.

It would be inaccurate to say that there aren’t any pitchers with S-JAWS similar to or lower than Buehrle in the Hall, but the ones who are there were either exceptional in ways not captured by WAR, or were small-committee choices that haven’t aged particularly well. Even given the dearth of recent starters in the Hall, I’m still wavering on Buehrle. It appears he’ll stick around the ballot, and while I don’t think he’ll get much closer to Cooperstown than he is now, he’ll be fondly remembered in Chicago and beyond.