Brewers alumni home run derby is a hit

The Milwaukee Brewers held an alumni home run derby as part of their 25th anniversary celebration of American Family Field on July 25, 2025.

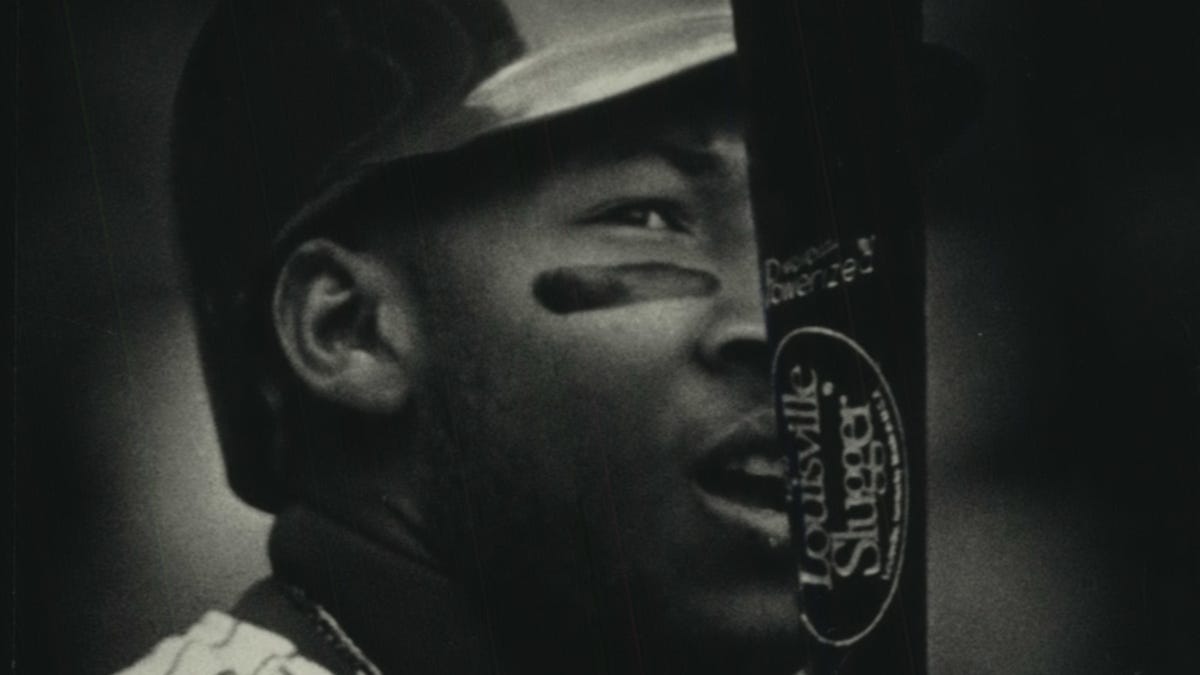

Former Milwaukee Brewers player Gary Sheffield will be among the players discussed for enshrinement in the Pro Baseball Hall of Fame on Sunday, Dec. 7 as part of the Contemporary Baseball Era Committee vote.

Sheffield, two years removed from failing to gain enshrinement via the traditional Modern Era vote, joins a list of players under consideration such as Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens, as well as Carlos Delgado, Jeff Kent, Don Mattingly, Dale Murphy and Fernando Valenzuela.

In a twist, the Brewers will be heavily represented on the 16-person committee. Robin Yount, the organization’s most celebrated player, is one of seven Hall of Famers on the committee. A group of six MLB executives includes Brewers owner Mark Attanasio and former Brewers general manager Doug Melvin.

Yount played alongside Sheffield when the top-flight prospect joined the Brewers as a 19-year-old in the 1988 season, the first of four tumultuous big-league seasons in Milwaukee.

In fact, Yount wasn’t spared from Sheffield’s strong criticism of the organization and its players after he was traded away from the Brewers, a move he likened in 1992 to the end of a prison term. At one point, he called Milwaukee “hell.”

Sheffield was met with boos every time he returned to Milwaukee, which he did in a career that lasted until he was 40 years old in 2009. Along the way, he made stops with the San Diego Padres, Florida Marlins, Los Angles Dodgers, Atlanta Braves, New York Yankees, Detroit Tigers and New York Mets.

Vilified for his comments – and perhaps his immediate success away from Milwaukee – Brewers fans never forgot.

But what actually happened to cause the rift between Sheffield and the organization?

Position switch, injury caused rift between Gary Sheffield and Brewers

Matthew J. Prigge of the Shepherd Express wrote a two-part retrospective in 2017 on Sheffield’s tenure in Milwaukee, starting his chronicle with the fifth pick of the 1986 draft. The nephew of Doc Gooden, with whom he had a longstanding close relationship, Sheffield had attracted national attention as a top high-school prospect in Florida, and he mashed in the minors even while battling homesickness. His spending habits also attracted the attention of writers, and his behavior – missing a team bus, getting benched for not running out a ground ball – went under the microscope.

He still became perhaps the biggest prospect the organization has ever had, and he was brought to the big leagues as quickly as possible, debuting as a teenager in 1988. Sheffield looked to have the inside track on the starting shortstop job in 1989, but he was moved to third base with incumbent third baseman Paul Molitor injured to start the year. Instead, the Brewers brought up a player they considered more surehanded at the position, Bill Spiers.

This generated the first considerable rift between Brewers and Sheffield. Even today, Sheffield believes he could have had more success if he had been kept at his “natural position” of shortstop, a spot he never played in the big leagues again after 1989.

During the 1987 season, he first expressed that the organization treated him differently because he was Black. He said he didn’t feel the veteran players had his back. He floated the idea of walking away, comments from which he backtracked but words that considered many to label him as a malcontent.

When he complained of significant foot pain, the Brewers suspected he was faking the injury to excuse his poor play, though a doctor later discovered that he was, in fact, playing with a fracture.

Sheffield rebounded in 1990, but the good vibes didn’t last

The Brewers added more Black personnel in 1990, signing Dave Parker – himself a recent Hall of Fame inductee through the veterans committee process – and hiring Don Baylor as hitting coach. Sheffield appeared to be on better terms with teammates and coaches and played at a high level again. But when the team traded Parker after 1990 and kept Spiers at shortstop, Sheffield’s aggravation returned.

He openly expressed contempt for general manager Harry Dalton, believed players like Molitor were reporting back to management on Sheffield’s actions and expressed disdain for manager Tom Trebelhorn. He also struggled with more injuries, including a serious shoulder injury that cut his 1991 season short. The Brewers went on a run without him, and Sheffield, Dalton and Trebelhorn all would be gone after the season. One week before the 1992 season, new general manager Sal Bando traded Sheffield to San Diego for Ricky Bones, Matt Mieske and Jose Valentin.

“I hated (Dalton) so much that I wanted to hurt the man,” Sheffield told Bob Nightengale, then with the Los Angeles Times, in 1992 in the midst of a strong first season with the Padres. “I hated everything about that place. I didn’t even want to come to the ballpark.”

In the interview, Sheffield implied he threw the ball away intentionally after disagreeing with an official scorer’s ruling. Though he backtracked, and nobody ever found evidence of a play that properly fit the description, it gave rise to the idea that Sheffield had done something of that nature, or was at least willing to.

In 1991, Sheffield made his first all-star team playing with the Padres, the first of nine such appearances. He went on to hit 509 career homers, steal 253 bases, post a career OPS of .907 and a career on-base percentage of .393. However, he received just 63.9% of the Hall of Fame vote (needing 75%) on the 2024 ballot, his final shot at a Modern Era election. Players who don’t get the requisite number of votes after 10 years are moved off the ballot.

The Contemporary Era committee will consider the aforementioned players, all of whom fit the description of contributing to the game since 1980. But the next chance after that is three years away. Next year, the same era will be considered, but only for managers and contributors. The year after that, a “Classic Era” committee will choose from pre-1980 players.

Each committee member can vote for three names, and players need 12 of 16 votes for induction. Others on the selection committee include players Fergie Jenkins, Jim Kaat, Juan Marichal, Tony Pérez, Ozzie Smith and Alan Trammell, executives Arte Moreno, Kim Ng, Tony Reagins and Terry Ryan and media/historians Steve Hirdt, Tyler Kepner and Jayson Stark.

Mitchell Report mention might also slow Sheffield’s candidacy, but is that justified?

Sheffield’s reputation for speaking his mind pervaded his entire career, and so did something else: His name appearing on the Mitchell Report during MLB’s investigation into performance-enhancing drugs.

Sheffield vehemently denies he ever took any banned substances from the Bay Area lab BALCO, at the heart of the steroid scandal in baseball. Sheffield wasn’t penalized by baseball after he admitted to a one-time use of an ointment cream that he wasn’t aware contained a steroid, given to him while training with Bonds after stitches on Sheffield’s knee burst open. BALCO founder and whistleblower Victor Conte said he never had a conversation with Sheffield about steroids.

Sheffield’s name appeared in the Mitchell Report because of a check written by his wife for less than $150 for legal vitamins from the BALCO facility. Sheffield said he had developed an aversion to all drugs after seeing Gooden’s career up-close.

“I played this game clean, and was proud that I played it clean,” Sheffield said to Nightengale again, this time in 2025. “Never, ever, did I cheat the game, and I’m proud of that.”