Welcome back to “On the Air,” in which Sports Media Watch Podcast co-host Armand Broady will offer in-depth breakdowns of broadcasters, on-air performance and career journeys, plus chronicle broader trends in the industry.

Last week, Joe Buck was named the recipient of the Ford C. Frick Award from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, joining his father, Jack, to form the only father-son duo to ever win the prestigious award for excellence in baseball broadcasting.

But while Buck may have seemed like an heir apparent to his father, his journey to baseball broadcasting immortality was no sure thing.

By the mid-1990s, the relationship between baseball and network television had grown rather tumultuous. CBS and MLB ended their stormy four-year association in 1993. Then came the ill-conceived Baseball Network on ABC and NBC, which was doomed in year one by the disastrous strike that shortened the season and canceled the 1994 World Series.

Having ended on bad terms with the “Big Three” broadcast networks of CBS, ABC and NBC, MLB was fortunate that Fox had burst its way onto the sporting scene by way of its shocking acquisition of the NFL’s NFC package, and in need of additional rights to justify being called “Fox Sports” — rather than “Fox Sport,” as John Madden joked.

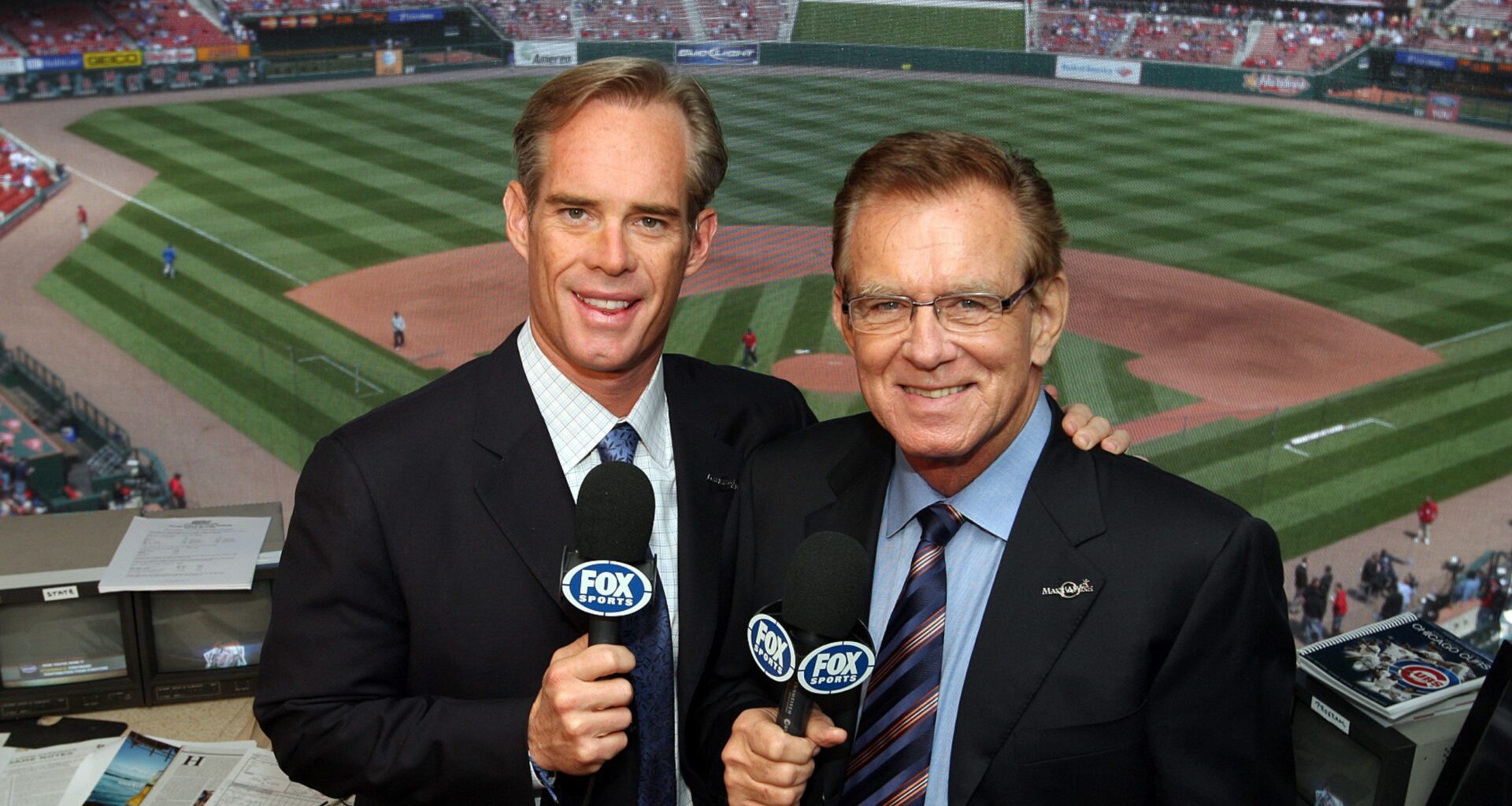

Upon its acquisition of MLB rights, then-Fox Sports president David Hill sought to do for the league what he and the company had done for the NFL. The brash, ambitious network looked to mix things up, to chart its own path with its own unique flair. The face of this new approach was a young Joe Buck who, along with Thom Brennaman, was described in a 1996 New York Times article as “the best play-by-play broadcasters nepotism can buy.”

Although Buck earned rave reviews for his performance that season, that one word … nepotism … would hang over much of his career like an ever-present pall.

Everyone knew he was the son of Jack Buck, the legendary broadcaster of the St. Louis Cardinals and CBS Radio and TV. Long before “nepo baby” became a common term, Joe Buck was facing a steady drumbeat of criticism for the way he reached baseball broadcasting prominence.

Detractors may have despised his path to the top, but objective observers could not deny his obvious talent. His 1996 call on the final out of the World Series — “The Yankees are champions of baseball!” — lives on in baseball lore, as do so many others. “Touch first, Mark, you are the new single-season home run king!” Buck memorably declared in 1998 after Mark McGwire’s 62nd home run.

In 2001, Buck — in one of the most dramatic moments in World Series history — delivered the succinct “Floater … centerfield … the Diamondbacks are world champions!” after Luis Gonzalez’s bloop hit to dethrone the Yankees.

To some, Buck was boring. To others, too refined, too polished. Some felt Buck was too loyal to his St. Louis roots. Some didn’t know why they didn’t like him. Whatever the reason, the criticisms seemed to swell. The naysayers were provided with more grist for the mill when, in 2002, Fox named Buck its lead NFL play-by-play announcer. The network was making a statement: Buck was its star.

That stardom came with its challenges. By his own admission, Buck tried too hard to be accepted. His underwhelming call of the Cardinals’ 2006 World Series is evidence of that.

“I hear them win the 2006 World Series, and my voice is so flat and so monotone and so not excited because I’m trying to prove to everybody in Detroit, I’m not rooting for the Cardinals,” Buck said last year on the Nothing Left Unsaid podcast. “Look, here’s the most boring call ever to end a World Series. It was a good learning moment for me because I heard it back. I was like, ‘Man, that’s just not fair. That’s not fair to fans in St. Louis.’”

In 2011, Buck famously suffered vocal cord damage, leaving his voice weak for months. He initially claimed the damage was caused by a virus, but he later revealed in his 2016 book Lucky Bastard: My Life, My Dad, and The Things I’m Not Allowed To Say on TV that the damage was caused by a protective cuff used while he was under anesthetic for a hair plug procedure.

As bizarre as it all was, something with Buck seemed to turn around that time. He was always a gifted broadcaster, but he had become something more. He sounded like he was finally comfortable just being himself. From about 2012 on, Buck’s play-by-play seemed to reflect a man who had broken free from his dad’s shadow and from the labels placed on him by critics in the stands, on the couch or on their computers.

The iconic calls continued. In 2013, he nailed a voice-cracking “TIE GAME!” after David Ortiz hit a grand slam in Game 2 of the ALCS. Three years later, the Cubs’ magical run led to numerous classic calls, including his unforgettable, “The Cubs … WIN THE WORLD SERIES! Bryant makes the play! It’s over! And the Cubs have finally won it all!”

From his Fox debut, it was clear Joe Buck had the broadcasting touch. But what makes his Hall-of-Fame honor so noteworthy is the extraordinary journey he took and the discoveries he made about himself along the way.

Plus: Watt sparkles during Bills-Pats broadcast

In the most important game of his burgeoning broadcast career, CBS NFL analyst J.J. Watt hit the right notes with energetic and insightful analysis. Too many football analysts use arcane terms to prove their knowledge, but Watt eschews this strategy in favor of a simpler, more digestible style.

As Patriots RB Treveyon Henderson raced towards the end zone for a 65 yard TD, Watt exuberantly pointed out the downfield blocking of Pats QB Drake Maye. It made for entertaining television. Watt exclaimed, “Drake Maye leading the way! What a block!”

As one might expect, Watt is at his best when he’s breaking down line play. Take his breakdown of a big 4th quarter run by Bills RB James Cook. With help from producer Ken Mack and director Suzanne Smith, Watt showed viewers via replay that the run succeeded because of RT Spencer Brown’s ability to get a block on a linebacker. Big runs don’t happen without good blocking, and the best analysts show viewers how those plays happen.

After a Bills 4th quarter TD, Watt crisply explained New England’s “picket fence defense,” describing via telestator that Pats defenders were lined up inside the 5 yard line playing zone coverage against Bills QB Josh Allen. This allowed TE Dawson Knox to find a soft spot in the end zone for the score.

It’s just his first year, but J.J. Watt’s unique perspective as a defensive lineman plus his enthusiasm and comprehensible style have made him one of the most promising young game analysts in sports television.