It feels, looking back, like Pablo López missed practically the whole 2025 season. He was sidelined for the key stretch in which the Twins flopped out of contention and sold off the roster for parts, and with the much shorter stints he spent on the injured list early and late in the campaign, it’s hard to remember the times when he was actually available. Somehow, though, he made 14 starts on the year, and he posted a stellar 2.74 ERA.

Since the Twins’ plan for 2026 appears to be giving it one more try with their familiar core, it will be important that López be similarly excellent (and a bit more sturdy) next season. Few players are more reliable or conscientious, though, and even fewer are more creative, so López is as good a candidate to have a great year as anyone in the projected starting rotation. He even added an interesting and valuable pitch to his mix this season: the kick-change.

López was thoughtful and cautious with his implementation of that new flavor of changeup. It’s a pitch that utilizes an altered grip to change the spin axis out of the hand, without a significant change in the way one manipulates the hand or forearm at release, and for López, it was extremely effective. In fact, there’s significant evidence that it’s better than his usual changeup.

According to Baseball Prospectus’s StuffPro and PitchPro, López’s original changeup is an average pitch, but the kick-change is a potential dominator. It’s 0.6 and 1.4 runs better than the standard change per 100 pitches thrown by those two models, respectively, which is a huge margin. That invites the question: Should López lean more into that offering (and away from the changeup he’s been throwing instead) in 2026?

To answer that question, let’s consider the shape and the characteristics of the two distinct cambios. Prospectus shows many of those numbers distinctly, because their pitch classification system can distinguish the regular change from the kick-change, but we can find more of it by teasing out which is which even on Baseball Savant—where all of these pitches are lumped under one ‘changeup’ pitch type.

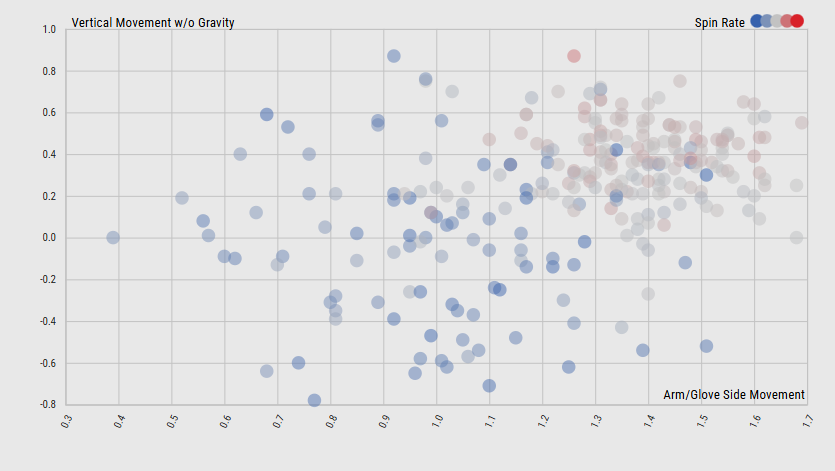

Here’s a chart showing López’s horizontal and vertical movement on all his changeups, via Savant, colored by spin rate.

As you might guess, the old, reliable changeup is the cluster of gray and reddish dots on the upper right. The kick change, by contrast, lives in blue. The intruding middle finger, which delivers that kick to change the spin axis for the kick-change, also kills some spin, which results in more depth on the pitch but less command. Note how much tighter the cluster of movement coordinates is for the old changeup than for the new one.

The dividing line for the two pitches turns out to be right around 1,800 RPM. Draw a line there, and you can get Statcast to show you (more or less) the vitals on the two different pitches living under one umbrella.

Spin Rate

% of Changeups

MPH

Hor. Mvmt.

IVB

Arm Angle

EV

LA

Zone Rate

Whiff Rate

xwOBA

Under 1,800 (CK)

36.7

87.6

12.2

-0.3

36.5°

87

8

30.6

33.3

.183

1800+ (CH)

63.7

87.2

16.5

4.3

34.8°

86

15

40.6

24.4

.405

It’s not quite as stark a situation as what we see here, because while we have almost exactly the right number of pitches in each bin (comparing the breakdown we roughed out with the count of each type of change on López’s Prospectus player card), a few of the wrong ones are in each. His highest-spin kick-changes are likely to be his least effective; his lowest-spin standard changeups are likely to be the most effective. Thus, the expected weighted on-base average for the two pitches isn’t actually as different as that table would imply. Still, there’s a huge difference here.

Notice that the kick-change has considerably less arm-side run, but (by the same amount) more vertical depth. That’s why it gets more whiffs and (as implied by the much lower average launch angle) more ground balls. However, you can see why López has been a little bit reluctant to push the pedal down and make the change from one flavor of changeup to the other: it’s that zone rate.

Less spin and more movement make it hard for López (or anyone else) to land the kick-change in the zone with any consistency. That’s a big part of why he stuck with the standard changeup almost two-thirds of the time, when he went to an offspeed pitch. Those same characteristics are also why the kick-change earns more whiffs, though. If he can consistently induce batters to chase outside the zone, then the inability to fill up the zone with the pitch will turn from a lurking weakness to a major strength.

Prospectus also offers estimates of the opposing batter’s ability to identify a pitch out of the pitcher’s hand, based on release point, initial trajectory and other factors, and introducing the kick-change did wonders for López in terms of introducing deception and uncertainty for hitters. The kick-change gets mistaken for his sweeper a plurality of the time against righties, and for his regular changeup equally often against lefties. He matches his arm angle fairly well on both changeups, trusting the grip to do the work of steering them differently. Having both appears to beat leaning into only one, although over a larger sample, that could turn out differently.

The question isn’t really whether the kick-change should replace the old changeup, then, but whether it might be wisest to reverse the share of his total offspeed portfolio made up by each. Should López throw the kick-change twice as often as the regular change, because it’s much more likely to draw whiffs and is a better overall pitch, based on shape and deception? Or would that lead to overexposure, and put him behind in too many counts?

López implemented the pitch slowly and carefully, knowing these questions are hard to answer without experimentation—but unwilling to experiment at the cost of his teammates’ chance to win on a given day. As he works this winter and goes to spring training, though, it’ll be interesting to see whether the kick-change gets greater market share in López’s offspeed attack in 2026. It probably should, but for that to work, he has to get the balance between inducing whiffs and letting hitters gain count leverage exactly right.