On Christmas Eve 1969, Flood sent the following letter to the Commissioner of Baseball, Bowie Kuhn.

December 24, 1969

Dear Mr. Kuhn:

After twelve years in the Major Leagues, I do not feel that I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the several States.

It is my desire to play baseball in 1970, and I am capable of playing. I have received a contract offer from the Philadelphia club, but I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decisions. I, therefore, request that you make known to all the Major League Clubs my feelings in this matter, and advise them of my availability for the 1970 season.

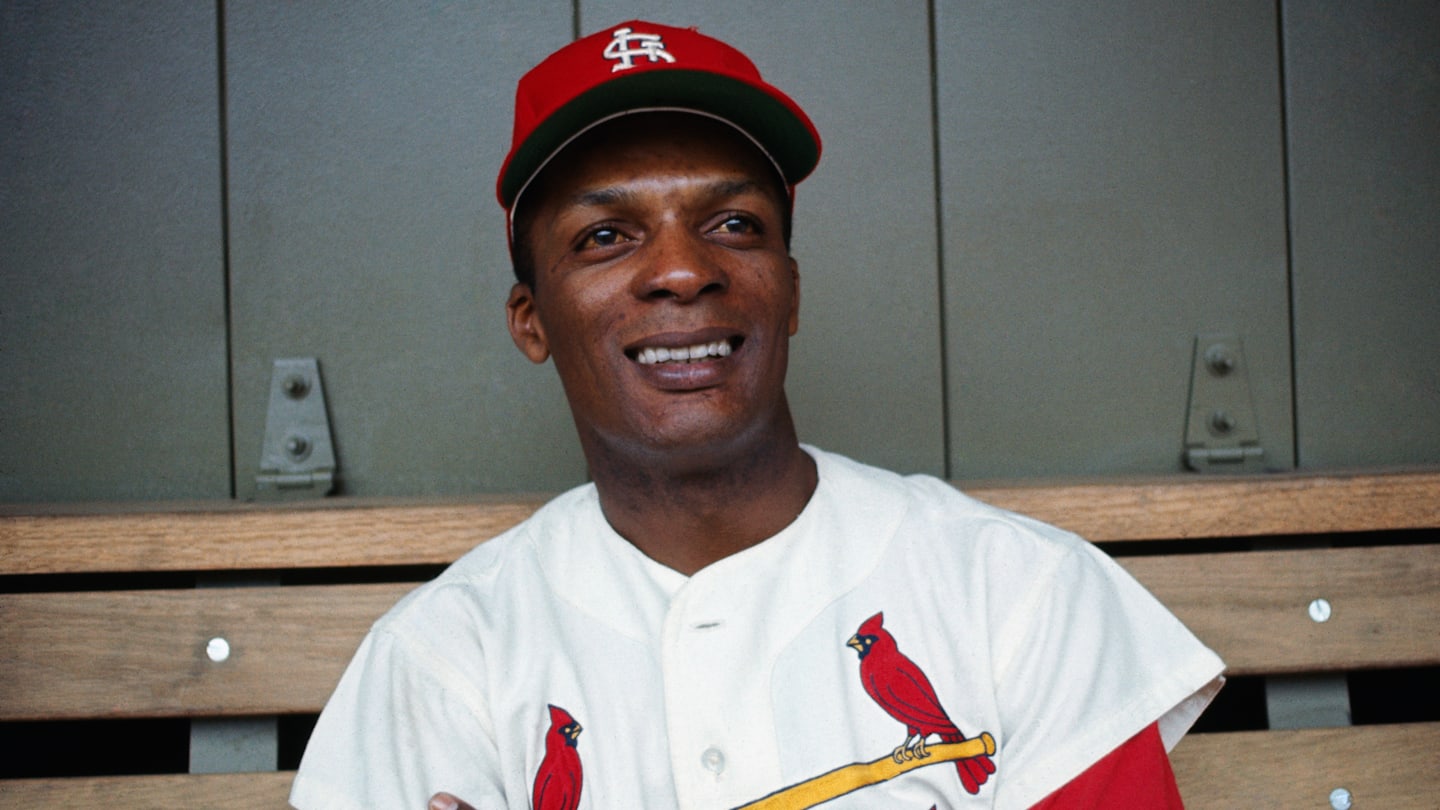

Sincerely yours, Curt Flood

Cardinals History: Those 138 words from Curt Flood changed the history of baseball forever.

After being in the World Series in 1967 and 1968, the St. Louis Cardinals finished fourth to the Miracle Mets in 1969. That year, the Cardinals ranked near the bottom of the National League in runs and home runs. General Manager Bing Devine was determined to acquire a “run producer” and targeted Richie (Dick) Allen, a superstar slugger who had a higher slugging percentage than almost anyone in baseball at the time.

On October 7, 1969, the Cardinals traded Curt Flood to the Philadelphia Phillies as part of a seven-player deal. The Cardinals sent Flood, Tim McCarver, Joe Hoerner, and Byron Browne to Philadelphia in exchange for Dick Allen, Cookie Rojas, and Jerry Johnson.

Flood only learned of the trade from a reporter, not the Cardinals. He spent the first few weeks in a state of disbelief and anger. He had played for the Cardinals for 12 years and had just opened a photography business in St. Louis; he was deeply rooted in the community and felt “discarded like a piece of property.”

To understand what he was feeling, it’s important to remember his trade was announced only 551 days after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Living through the peak of the Civil Rights Movement and the social upheaval following Dr. King’s death heavily influenced Flood’s refusal to be traded.

Howard Cosell on ABC’s Wide World of Sports, pointed out in an interview with Flood that he was earning a high salary for the time—$90,000 a year—and asked how he could justify his stance given those earnings. Flood replied: “A well-paid slave is nonetheless a slave.”

Flood spent December meeting with Marvin Miller, the head of the Players Association. Miller warned Flood that if he challenged the reserve clause rule in court, he would almost certainly lose and probably end his career. Flood notably replied, “But if we won the case, wouldn’t that benefit all the other players? … That’s good enough for me.” He retained Arthur Goldberg, a former Supreme Court Justice, to represent him. The case eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1972 as Flood v. Kuhn.

The decision was 5–3 against Flood. Justice Harry Blackmun wrote the majority opinion, which is one of the most unusual in legal history. Even though Blackmun admitted that baseball’s antitrust exemption was an “aberration” and “illogical,” he refused to overturn the exemption. The first Black Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall, voted in Flood’s favor.

Marvin Miller, at the same time Flood’s case was winding through the system, was negotiating a new CBA for the players. He had the owners insert an arbitration clause in the contract. Just as he predicted, Flood lost. But on October 7, 1975, exactly six years after the announcement of Flood’s trade, Andy Messersmith filed his grievance. On December 23, 1975, one day short of the anniversary of Flood’s letter to Kuhn, free agency in baseball was a reality.

Curt Flood may have lost his case, but it accomplished many things. It created a path for Andy Messersmith. Flood’s refusal to report to Philadelphia directly led to the first-ever formal trade-veto power in MLB. In 1973, as a compromise following his lawsuit, the league adopted the “10-and-5 Rule.” This established that any player with 10 years of service in the major leagues and 5 consecutive years with the same team can veto a trade.

The Curt Flood Act of 1998 was a historic piece of legislation that finally addressed the “legal anomaly” the Supreme Court refused to fix in 1972. It was signed into law by President Bill Clinton on October 27, 1998. The primary purpose of the Act was to give Major League Baseball players the same rights under federal antitrust laws as athletes in other professional sports like the NFL or NBA.

President Clinton’s remarks when he signed the bill sums it up very well:

“It is especially fitting that this legislation honors a courageous baseball player and individual, the late Curt Flood, whose enormous talents on the baseball diamond were matched by his courage off the field. It was 29 years ago this month that Curt Flood refused a trade from the St. Louis Cardinals to the Philadelphia Phillies. His bold stand set in motion the events that culminate in the bill I have signed into law.”

Hopefully, the next event will be seeing Curt Flood enshrined in the Hall of Fame.