Image credit: © Darren Yamashita-Imagn Images

I was very much under-equipped for the task, but in my seven years with the Marlins, I was the go-to analyst for East Asian baseball data. I had previously built decent major league equivalent (MLE) models for The Hardball Times annual, and my knowledge of Japan, Korea, and Taiwan’s general baseball culture and trends made me slightly more qualified than a stranger off the street, but it was a colossal and tumbling learning experience nonetheless.

One of my first big pushes was for Yoshitomo Tsutsugo.

Baseball fans outside Tampa Bay and Pittsburgh could be forgiven for not recognizing the name Yoshi Tsutsugo. He was an exceptional hitter in the Nippon Pro Baseball (NPB) league in Japan from 2014 to 2019, posting a .298/.397/.559 slash line with an average of 33 HR per 600 PA, good for 155 wRC+.

“Hitters this good don’t usually cross over to America,” was the summary line for my analysis of Tsutsugo. The Marlins had little budget for international risks, and the Analytics Department had little political capital to spend on mistakes.

“Can he hit velocity?” my boss, Assistant General Manager Dan Greenlee asked me.

It was a good question. The highest velocity starting pitcher in the 2019 NPB season was Kodai Senga at 153 kph. Which sounds great in kilometers per hour, but in miles per hour, his 95 mph velocity would only rate as 10th best among 2019’s qualified MLB starters. Only Senga and Yoshinobu Yamamoto averaged above 92 mph among qualified starters in Tsutsugo’s final NPB season—and he never saw either of them. Neither pitched in the Central League.

So Dan was right to ask. Few NPB hitters even see 95+ or 97+ pitches, and even fewer see them with any frequency. The Marlins had a data sharing arrangement for Trackman pitch-by-pitch data for about half the stadiums in Japan. And in that data set, the typical starting position player was seeing only about 20 to 30 pitches per year over 97 mph—and very often, those were all pitches thrown by the same pitcher.

Facing big velocity doesn’t just mean trying to hit a hard fastball. It often also means facing hard sliders, or gearing up for big velo while still keeping the hands back for off-speed pitches—nope, nevermind, it was a fastball; now you’re late.

There’s an adjustment curve for NPB hitters that does not have a parallel for pitchers. Yes, NPB pitchers have to learn how to pitch the same while using a different-feeling, often less-tacky MLB baseball. But they can get a bucket of balls and bring them to their backyard. It’s very hard to find someone to throw you BP in the backyard at 100 mph, tossing in a few 93 mph sliders to keep you on your toes.

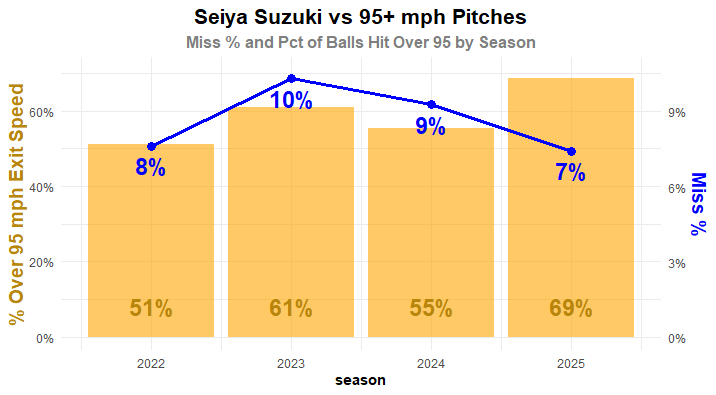

Consider Seiya Suzuki‘s performance against velocity over the first 3 years of his MLB career:

In his first MLB season, Suzuki performed really well against high-velo pitches, given his limited exposure to velocity in Japan. But with each successive season, he has steadily improved his exit velocities (measured here as % Over 95, or the percentage of balls with an exit velo over 95 mph) while also improving his misses against these pitches.

This all brings me to the matter at hand today, the reason you opened this article. Let’s talk about who in Japan is hitting right now. And who is likely to hit in the majors.

With the Marlins, I built a MLE model that took advantage of batted ball data that stabilizes much faster than the typical results metrics like OBP, SLG, and wRC+. Unfortunately, that model and its corresponding data are now locked away. But we can deploy some of the lessons learned and create metrics akin to the old one that successfully predicted the guys like Seiya Suzuki and Masataka Yoshida would hit in the majors—and rightly rained on my parade for Yoshi Tsutsugo.

The Simple Model

“His performance against high velocity is actually good, if you ignore the strikeout rate,” was my tepid summary to Dan. Thanks to data from DeltaGraphs, we can see Tsutsugo has had 130 PA against pitchers who threw 94 mph or harder in Japan, and he had managed an impressive 147 wRC+ with an eye-watering 43% K rate. Tsutsugo used the approach that so many DSL hitters have found success with—before their careers fizzle out in Double-A: Wait for the fireballer to walk you.

So the first major improvement I made to my old Hardball Times MLE model: Consider performance against velocity.

Today’s first model is quite simple, so let’s call it the Simple Model. It has two inputs, though granted, those inputs are quite specific and somewhat complicated metrics:

Simple Model = 38.9 – [K% vs 94 mph Pitchers] * 54.5 + [NPB wRC+] * 0.46

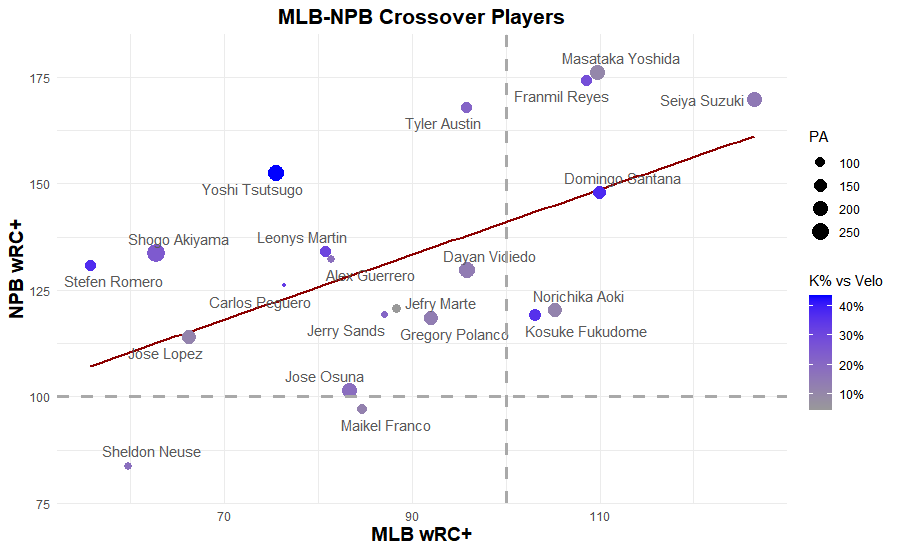

This model is essentially the information found in this plot:

These are the players since 2016 who have gone over the Pacific, in either direction, and faced at least 50 PA of high velocity in Japan, as well as 200 PA of any kind in the MLB. The model is quick and dirty, but ultimately intuitive. Looking at the players it holds in high regard since 2016, the names should come as no surprise:

This Top 20 passes the proverbial sniff test for me. Franmil Reyes is a few years removed from his best years, but was easily a 110 DRC+ hitter from 2018 through 2021. Yoshida and Suzuki are both in their current neighborhoods for MLB production. Tyler Austin is a bit more of a head-scratcher, but he has posted an overall K% under 20% over the last two seasons, so maybe there’s some improvement going on there.

You may notice something else about this leaderboard—even though we’ve got K% vs Velo in the model, it can really be summed up as, “Subtract ≅50 points from the player’s wRC+ in Japan.”

I think that’s a handy and sobering rule. The K% against 94+ mph pitchers is a meaningful input, albeit not the most important, as we can see here:

But let’s explore a second style of model. We’ll call it the Component Model. It was quite effective with batted ball metrics (as data like max exit velocity stabilizes way faster than SLG, HR%, or wRC+), but even without those inputs, we can make a reasonable sanity check for our Simple Model.

The Component Model

The Component Model is a model of models. It works like this: I found that predicting K% from NPB data was much more reliable than trying to predict the whole shebang (wRC+, DRC+, or some other “complete hitting” metric). The same was true of BB% and exit velocities. We can then combine these components to project a complete hitting metric. In fact, our internal offensive metric (which was very comparable to DRC+) could be imputed through just those three essential pieces with reasonable error bars.

So first we model strikeouts:

K% Projection = 0.028 + [NPB K%] * 1.1

Simple enough.

Then we predict walk rate—and here, I found using BB% vs 94+ mph pitchers to be a powerful addition to this version of the model:

BB% Projection = 0.011 + [NPB BB%] * 0.351 + [BB% vs Velo] * 0.268

In cases where the batter has not faced enough velo pitchers, we can default to:

BB% Projection Alt = 0.013 + [NPB BB%] * 0.623

And we model for SLG, the weakest of the three models, though none are perfect:

SLG Projection = 0.24 – [NPB SLG] * 0.406 – [K% vs Velo] * 0.18

As well as:

SLG Projection Alt = 0.23 – [NPB SLG] * 0.34

Then using these three-ish models, we can predict (with an 0.82ish r-squared) DRC+. Well, I say we can predict it, but really we’re stacking errors upon errors here, so I would not make a multi-million dollar bet on these results.

DRC+ Projection = -25.8 – [K%] * 98 + [BB%] * 275 + [SLG] * 276

Nonetheless, we get a top 20 leaderboard that looks like this:

It’s really hard to impress this Component Model, but that’s okay. This is more our sanity check than anything. We are still seeing the right names float to the top—Yoshida, Suzuki, and two of my favorites from afar, Kensuke Kondoh and Yuki Yanagita, neither of whom will likely play in MLB. Likewise, we see a sensible correction with Tyler Austin (-17 points) and a draconian punishment of Franmil Reyes (-27 to a 77 DRC+ projection).

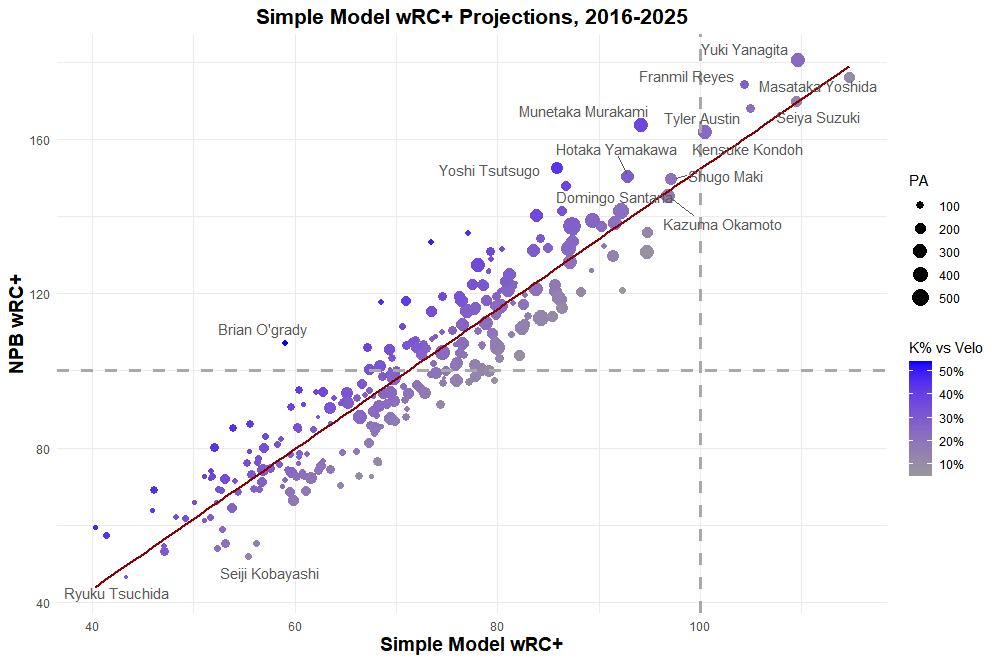

In total, the models pair up like this:

Yoshida and Suzuki are rightly living in rarified air, and Kondo lives on a tantalizing periphery.

The Shohei Problem

Now, I’m told there’s another Japanese slugger in the United States these days, and some may find it curious that I haven’t mentioned him after 1,800 words. Yes, would you believe that Shohei Ohtani—who has almost a .900 OPS against power pitchers according to Baseball-Reference—only had 33 PA in Japan against 94+ mph pitchers?

I tried multiple iterations of these models to try to get Shohei’s ample MLB data into works (despite his somewhat thin NPB data), but for some reason, his presence in the training data invariably undermined the explanatory powers of every. Single. Model. It’s almost like he’s a multigenerational outlier with absurd physical abilities. It’s almost as if he lives with someone who can throw 100 mph BPs in the backyard. (The velocity is coming from inside the house!)

So sadly, Shohei does not play a major role in this tableau. Instead, we shall turn our attention instead to the new entrants.

The 2025 Hitters

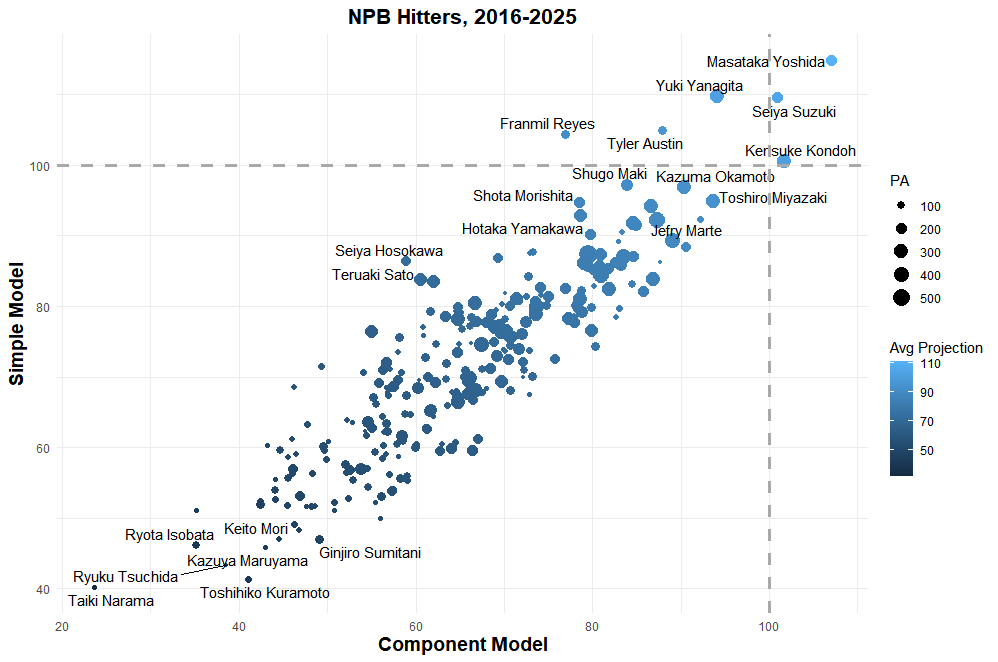

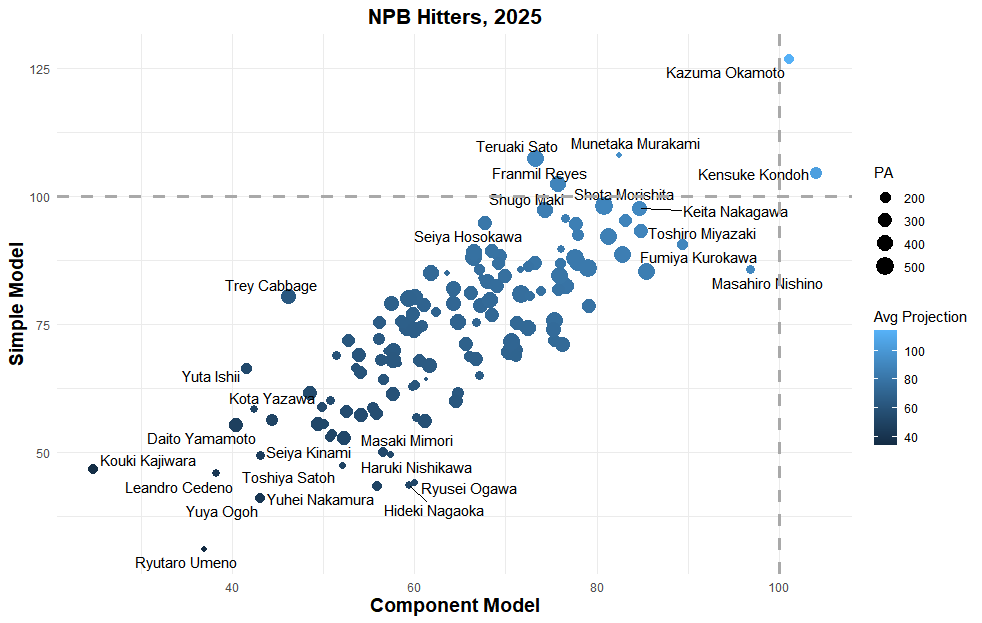

Now that we have finished with the preamble, we can examine the crop of current NPB hitters. How do their data in 2025 rate according to our two models? Using 2023 through 2025 data for high-velo pitchers, we get this group of top hitters:

Visualized, the total group looks like this:

Our friend Kensuke Kondoh shows up here again. A quick word or two about him:

Kondoh, sometimes spelled “Kondo,” plays LF for the Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks, having signed a seven-year deal with them as a domestic free agent in 2022. The DeltaGraphs WAR calculation has him at about 48 WAR for his NPB career, holding a career 161 wRC+. All from a guy who averages about 12 HR and 6 SB per 600 PA. He’s an on-base machine, sporting the coveted Jackie Robinson ratio, a term of my own devising to describe guys who walk more than they strike out and are also very cool.

Kondoh is a solid left fielder, but still a left fielder, and thus has accrued almost -37 runs of value on defense. He does not steal bases. He’s only crossed the 20-homer barrier once in his career. He isn’t the Japanese Willians Astudillo. No, Willians Astudillo is the Venezuelan Kensuke Kondoh. And if that doesn’t make you love him, then maybe baseball isn’t romantic anymore.

Will he ever play in MLB? Almost certainly not. Teams are having enough trouble trying to figure out if Luis Arraez is good. They don’t need a second obelisk of oblique value plopped onto the sport. I just thought you’d like to know about him. Also, he’s locked in with the Hawks for several more years.

Very interestingly—and quite concerningly because of his ongoing injury struggles—the models disagree quite sharply on Munetaka Murakami, the man who was expected to be the Big Name in the coming offseason. He’s still just 25 this season, and will no doubt continue to garner a lot of attention, thanks in part to his astounding 56 HR campaign in 2022. But he shows similar strikeout issues as our friend Tsutsugo, and his defense at third base has never graded out very well. I think Murakami will still be worthy of an MLB shot, but I do harbor fears about the volatility in these projections. And what kind of contract will ultimately be required to land him.

Let’s talk about Kazuma Okamoto.

We Can Talk About Kazuma Okamoto

He is a guy you’ve probably seen before, but don’t know it. Here he is hitting a home run in one of the most iconic series in recent baseball history:

Not only does Okamoto appear at the top of this leaderboard, not only does he top both projection models, not only does he have 244 career HR and an average of 33 HR per 600 PA—not only all of that, he also is expected to be posted this coming offseason. All that’s missing from this incredible set up is injury uncertainty of his own—but wait! Look no further than May 6, when a collision at first base caused him to go on the injured list, where he remained until just 12 days ago. Now he’s furiously mashing his team back towards .500, with a 181 wRC+ in August, while trying to mash himself into the realm of international relevance at the same time.

Okamoto plays both 3B and 1B with regularity. DeltaGraphs UZR has him as a solid 3B, with more iffy results at 1B. My previous work with the Marlins found there is some signal with Japanese UZR numbers, but not strong enough that I would presume much. What these two models particularly like is Okamoto’s steady hand against velocity. He has 332 PA against high velo pitchers, and owns a 148 wRC+ and just 17% K rate against them. The numbers are very comparable to Seiya Suzuki (166 wRC+ and 15% K rate against velocity).

Is Okamoto a lock for MLB performance? Hardly. I would say all of these models come with a +/- 20 error bar. Moreover, as with domestic players, there is always injury and aging risk with any player. But I am hopeful Okamoto can do it. He is certainly better equipped for the job than you or I.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.