Baseball might not be broken quite yet.

For what feels like a very long time, Major League Baseball has been trying to solve the issue of increasing strikeouts, less contact, and what many deem to be “boring” baseball. I’d argue a lot of that boring is beautiful, but that’s an argument for another day. I won’t fight anyone who thinks high strikeout rates are lame. Steps such as implementing the three-batter minimum (good), banning the shift (good), constantly tweaking the baseball (bad), and now the semi-automatic strike zone and challenge system were all taken to combat soaring strikeout rates, some to more success than others.

Fortunately, there’s evidence arising that strikeouts are coming back down of their own accord, and even some suggestion this could be sustainable, even before we see what impact a more consistent strike zone, at least when the challenge is employed, will have. Tom Tango, an analyst with ESPN, a co-author of The Book, and an icon for advanced statistics, dropped this bit of insight in December.

That’s right. After spiking around 2020, whiff rates against fastballs of all velocities have been on the decline. Overall, that’s led to a whiff rate on fastballs lower than any year since 2016. This alone is one small step in the right direction for the return of contact-oriented baseball. However, this wasn’t quite enough for me – here I go, asking why again – so I took it upon myself to expand upon Tom’s work.

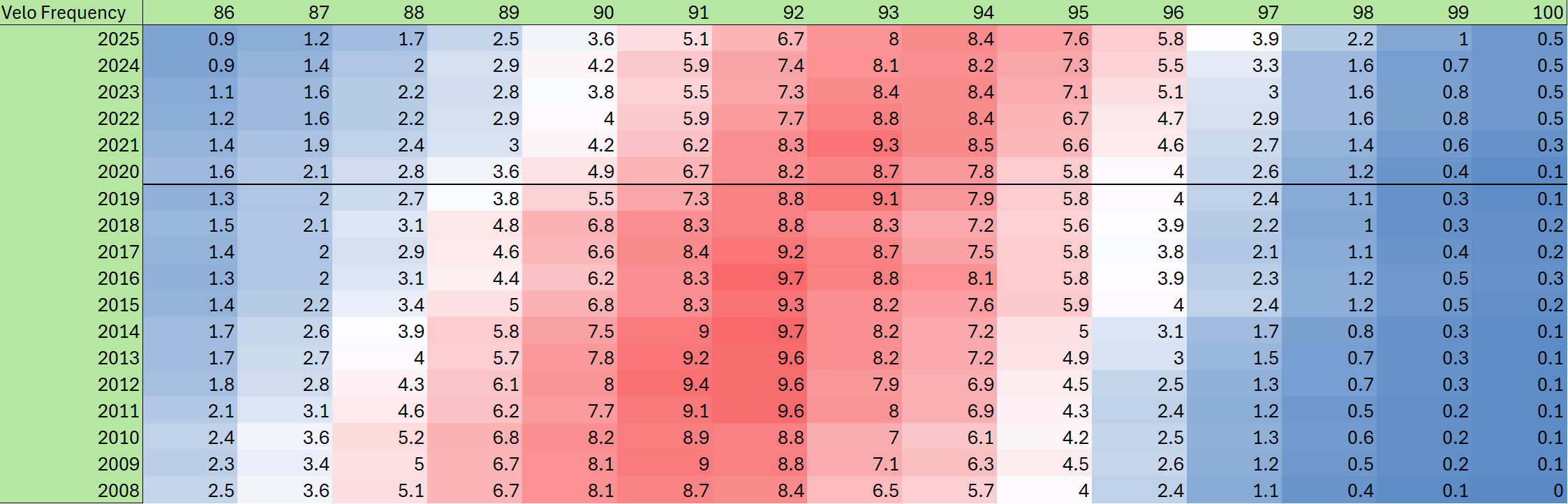

The first idea I wanted to check was if hitters were seeing high-velocity fastballs more often. That could suggest hitters are getting used to these fast fastballs and can handle them better than they used to. To do so, I recreated Tango’s chart, with fastballs bucketed into 1 mile-per-hour groups every year going back to 2008. For each group in each year, I checked what percentage of total pitches that group was. For example, in 2020, fastballs thrown between 96 and 97 mph were 4% of all pitches seen. Here are the results:

Fastball frequency per year, bucketed by velocity, 2008-2025

This confirms what we already expected: fastballs are being thrown harder now than ever before. The entire chart has shifted right; there are fewer slow ones, more fast ones, and a higher median value than ever before. It’s probably fair to say hitters’ jobs have never been harder, and the further back you go, the more true it is. 2008 didn’t have a single fastball over 100 mph, while last year 0.5% of all pitches came in that hard!

And yet, despite the seemingly incessant increase in velocity, Tango’s data shows whiff rates are going down. We know that in any given year, a harder fastball will get more whiffs than a slow one, but year over year, fastballs are being thrown harder and getting fewer whiffs. This strongly suggests hitters are adapting naturally to the proliferation of hard heat.

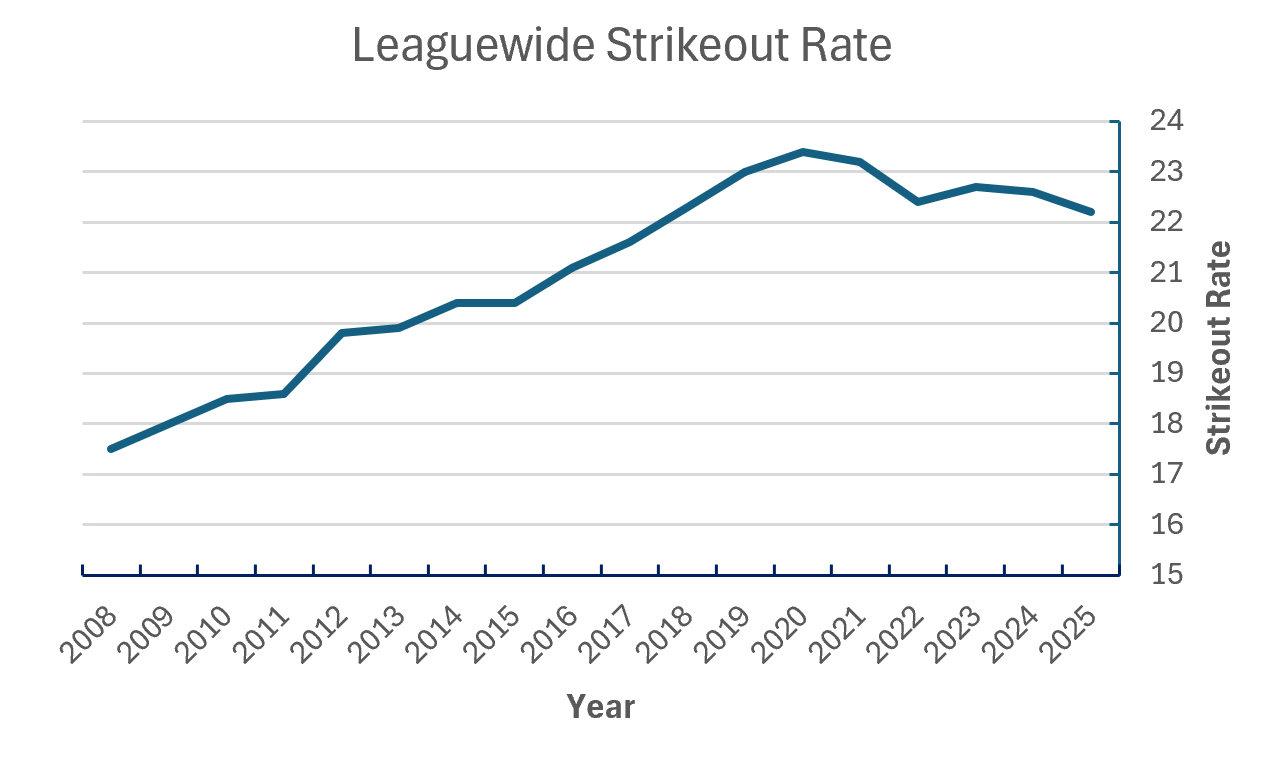

Theoretically, this suggests some stickiness to the declining strikeout rate. It might not have felt like it, but 2025 actually had the lowest strikeout rate since 2017 at 22.2%. In 2021, just four years ago, 23.2% of at bats ended in a strike out. That’s an extra 1% of plate appearances ending in contact, or over 1,800 extra balls in play. Put visually:

Obviously the league has quite a ways to return to a strikeout rate in the teens like we saw for most of the 2000s and into the 2010s. Teams are already combating the declining effectiveness of fastballs by simply throwing them less, particularly for pitchers who don’t have a particularly good heater. Honestly, the odds are it never will drop fully without further rules changes in order to force hitters to re-emphasize a contact approach. However, simply staving off the climb of the early 2020s has been a pleasant surprise. Any continued drop would be a nice bonus and something to keep an eye on in 2026.

I did then want to check how this impacted batting average, and unfortunately, that hasn’t rebounded equally. All that extra contact has resulted in the leaguewide batting average jumping from .244 in 2021 all the way to…. .245 in 2025. That’s a letdown. Despite having 1% more balls in play, hitters got hits .1% more frequently. Much of that disappointment comes down to improved defenses. The league actually posted a lower BABIP in 2025 than it did in 2021, before the shift was banned! Improved defensive positioning has made it harder than ever to get a ball to drop in, which is the main reason strikeouts jumped in the first place. When it became obvious that making contact was only consistently better than striking out if you made exceptionally good contact, hitters stopped fearing strikeouts and instead started to chase power.

If the league really wants a more entertaining product, it will take more than exchanging some strikeouts for some fly ball outs. Rewarding all types of contact, not just barrels that could be home runs, is the real final step to cut strikeouts down. That’s the only real way to incentivize more hitters to go for contact rather than power. The good news, though, is the first step is already happening organically. Finding ways to get more ground balls to go for hits, perhaps with a return to firmer, faster infields, would be one example of a way to start accomplishing the second step.

As harder fastballs become more common, hitters are seemingly becoming less phased by sheer heat. Until a new level of velocity is uncovered by more than elite closers like Mason Miller and Jhoan Duran, it looks like the league is moderately safe from continually rising strikeouts. Your move, Riley Greene. Of course, what happens when hitters do put the ball in play hasn’t yet improved the way we’d like, but this is still forward progress. As a fan of fun baseball, I can confidently say I’m glad to see this trend emerge and am hopeful it persists.