Watch Brandon Sproat on video, and it’s immediately clear that he’s not like most Milwaukee Brewers pitchers. In fact, he’s not like many pitchers you’re used to seeing, period. A product of the University of Florida, Sproat famously bet on himself by declining to sign with the Mets after his junior year, only to go one round earlier to the same team the next year. He’s unafraid to go a bit against the grain, and that shows up in his mechanics and his approach to the game. By making him a co-headliner in the Freddy Peralta trade this week, the Brewers made a significant bet on their ability to bend Sproat’s skills to their own purposes.

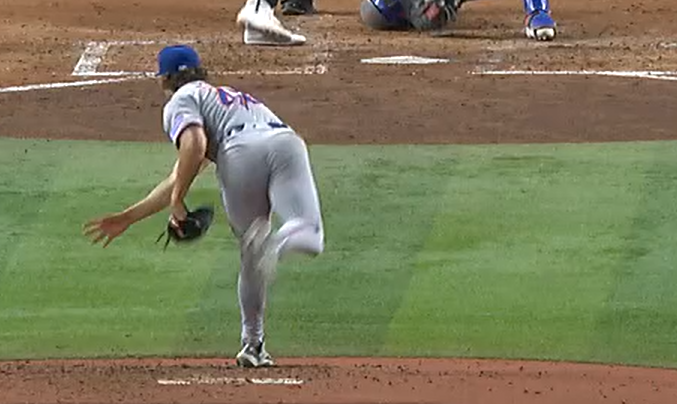

Here’s a fastball Sproat threw during one of his handful of big-league appearances at the end of last season.

OHlCRFBfWGw0TUFRPT1fQWdoVUJsWURWMVFBQ0ZVQ1Z3QUhDUTRFQUZnTVVWWUFCQU1OQXdvQUJRQUdWVkJm.mp4

That’s a high-effort delivery, with a bit of herk and jerk to it. The immediately unusual thing you probably noticed is that, after he breaks his hands and brings the ball down by swinging his elbow out toward full extension, he never again has his elbow bent more than 90° for the duration of his delivery. His arm action is exceptionally long, because he’s not winding it up the way most modern pitchers do. Instead, he’s really using his whole body to launch the ball toward the plate, and his hand merely carries it until it can’t hold on any longer.

Here’s something you might have missed in a quick viewing, but which is equally peculiar. He finishes his delivery of the heater with all four fingers splayed and his hand wide open. He looks like a man stretching out his hand for a book or a glass of water, left at an awkward spot just to his left.

Pause and examine the hand position of just about any pitcher after they throw their heater, and you’ll see some curl to their fingers. Their third and fourth fingers probably stayed tucked into a relaxed semi-fist throughout, and the first and second usually show the signs of having pulled hard at the seams at release, trying to maximize backspin. Not Sproat. His hand gives the impression that he simply surrounded the ball and flung it on its way when the extreme torque of his sturdy body dictated that he do so.

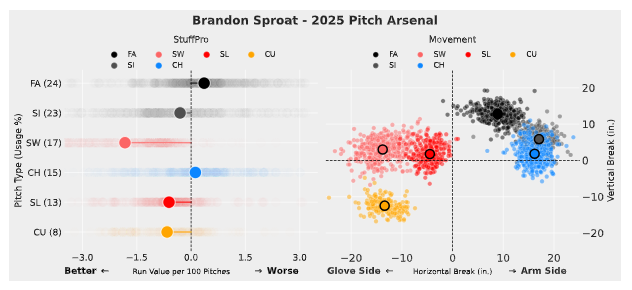

It might not surprise you, then, to learn that Sproat has a below-average spin rate on his four-seam fastball. Indeed, for each of his pitch types, the typical righty working from his low three-quarters slot gets more spin than he does.

Let’s circle back, though, to that long arm action. To underscore the extent to which this is a departure from the norm, I’ve captured the moment at which several pitchers’ front foot touched the ground while throwing their fastballs—what pitchers call ‘foot strike’. This is always a telling moment within the tornadic miniature ballet that is a pitch. Here, we see (clockwise, from the top left) Jacob Misiorowski, Sproat, Brandon Woodruff, Peralta, Chad Patrick and Quinn Priester at that moment.

.png.23ba91ae55da1fdd1822cfb7c2224c49.png)

Instead of a significant elbow bend and the ball near his ear, Sproat gets to that point with his hand a good two feet behind his head and his arm much closer to straight. Note, too, that his posture and stride direction are most similar to Peralta’s, but that he sets up on the first-base side of the rubber, as all the hurlers here except Peralta do.

This delivery has worked for Sproat, in a sense. It’s brought him this far, and it allows him to throw his fastball upwards of 96 miles per hour, on average. However, if this is all the athleticism and feel he has in him, his future is almost certainly in the bullpen. His four-seamer lives almost perfectly in the movement dead zone, based on his arm angle. His sinker is a better pitch, but it’s only effective against right-handed batters, and it cannibalizes his changeup. He has three above-average breaking balls, but no way to get to them against lefties, and as a starter, he’ll see a lot of left-handed batters every fifth day.

The Brewers are likely to make some major changes to Sproat’s game, if he’s amenable to them. A move across the rubber makes a lot of sense, at least on an experimental basis; he needs to find out whether the change in angle would do anything for his arm action or movement. The team will also explore the extent to which they can alter how he moves, though.

By and large, it’s hard to change fastball shape, and it’s hard to give pitchers with little feel for spin that skill. However, there are two things working for the Brewers with Sproat. First, he does show some feel for spin; it’s just exclusive to his breaking balls. Relatedly, he throws one of those breaking balls—his curveball—from a higher slot than the rest of his offerings. On the left, below, is him throwing a curveball. On the right is him throwing his four-seamer, in the same game.

.png.d2526a8f4cd1a8f84c5c988456edb23f.png)

A move on the rubber and/or a change in his arm angle could unlock something new for Sproat. Right now, he’s better off leaning on his sinker and avoiding his four-seamer, but that need not necessarily be true if he changes his delivery somewhat. The Brewers like to get a cutter working opposite the sinker in cases like this, and although Sproat’s lower slot (the one he uses for most of his offerings) isn’t conducive to a cutter, the higher one could be.

If no mechanical changes will take, the Brewers still have ways to optimize Sproat. He should scrap the curve unless he can find another pitch to execute from that same arm slot; he doesn’t need it with his present mix and set of looks. He should also avoid using his sinker to lefties, leaning on the four-seamer to set up the changeup. This spring will give Chris Hook, Jim Henderson and their cohort an opportunity to shine. The Brewers brought in a hurler with exceptional arm strength and a few intriguing secondary elements, but one nowhere near ready to thrive in the majors on the team’s usual plan. They’ll need to formulate a plan that helps him turn the corner, or else be ready to convert him rapidly into a high-leverage reliever. Sproat’s feel for spin and his command are important, but starting next month, his shot at taking his career to the next level will depend on his feel for communication and his willingness to relinquish some control of his development.