Welcome to part eight of North Side Baseball’s offseason series covering the 1918 Chicago Cubs. You can find the first seven parts here:

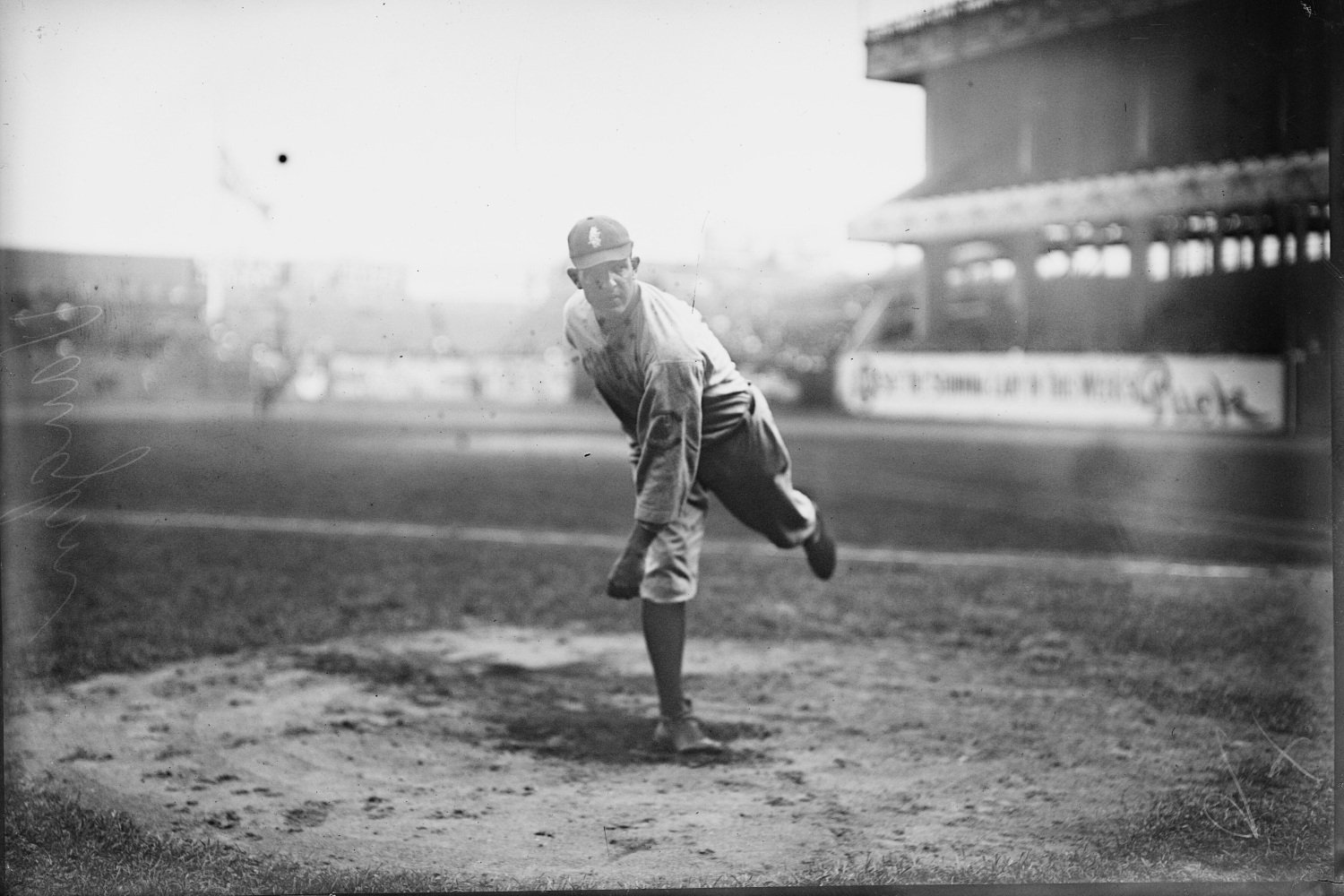

Today, we’ll be doing another player profile, this time on the great Hippo Vaughn. By FanGraphs WAR, Vaughn is the best left-handed pitcher to ever don a Cubs uniform, and he was an essential member of that 1918 Cubs team, leading the pitching staff in fWAR. His 1.74 ERA that season was second among qualified pitchers, behind only Hall of Famer Walter Johnson.

Vaughn never made the Hall, but deserves to be recognized for his contributions to the Chicago Cubs.

James Leslie “Hippo” Vaughn was born on April 9, 1888, in Weatherford, Texas, a town located about 25 miles outside of Fort Worth. According to his Society for American Baseball Research biography, the young lefty began pitching professionally in the Texas League, where he was eventually recognized and acquired by the New York Highlanders—or, as you likely now know them, the Yankees.

Vaughn would become the youngest Opening Day starting pitcher in Yankees history in 1910, at 22 years and five days old—a record that he still holds today. He would go on to post a stellar 1.83 ERA in the 1910 season, but following a more difficult 1911 season that saw him put up a 4.39 ERA, Vaughn was sold to the Washington Nationals, and then to Kansas City of the American Association.

After a couple of impressive seasons there, Vaughn wound up on the Chicago Cubs, and it was there where his career really took off. Following a brief debut of 56 innings in 1913, from 1914 to 1920, he never had a season wherein he posted less than 3.8 fWAR, and he never produced an ERA higher than 2.87.

From 1914 to 1920, per FanGraphs, his 33.6 WAR was third in baseball, behind only two future Hall of Famers: Walter Johnson and Grover Alexander. The latter, ironically, was Vaughn’s teammate in Chicago for a bit. Vaughn’s 2.16 ERA over those seven seasons was fourth. His 143 wins was third. His 165 complete games, 2,051 innings pitched, and 1,071 strikeouts all also ranked third, behind the aforementioned greats. Any way you slice it, he was one of the best pitchers in baseball for a time.

There is no greater illustration of how dominant Vaughn could be than the game he started on May 2, 1917. It featured him against Fred Toney of the Cincinnati Reds. Both pitchers threw no-hitters through nine innings, though, of course, the score was tied at 0-0, so the game persisted into the tenth.

In a retrospective on the game from 1953, Arthur Daley at The New York Times wrote the following about Vaughn:

“Vaughn, perhaps, pitched a mite better than Toney because only one member of the Reds even stroked the ball beyond the infield.”

Daley would go on to describe the top of the tenth inning, when Vaughn finally allowed a hit (and, unfortunately, a run) that led to a 1-0 Reds win.

“Larry Kopf sliced a roller between the gloves of Fred Merkle at first and Larry Doyle at second. It was the first hit of the game,” Daley wrote. “Then Hal Chase flied out deeply to [Cy] Williams—except that Williams dropped the ball for an error, as Kopf raced to third.”

That brought up Jim Thorpe, who hit a little tapper out in front of home plate. Vaughn, likely knowing that he would have a tough play on Thorpe, a former Olympic gold medalist in the classic pentathlon and decathlon, threw home. Art Wilson, the catcher, never saw it coming, and the ball “shot past him to the backstop and Kopf pattered home from third base with the only run of the game.”

Toney retired the Cubs without a hit in the bottom half of the tenth, completing his no-hitter and wrapping up the win for the Reds. Still, this is the only known game in baseball history where two pitchers both had no-hitters through nine innings of baseball.

Unfortunately for Hippo, who was given that nickname due to his large stature for a player at the time at 6’4”, 215 lbs, he is also commonly known for the way that he left baseball. He was not his usual, dominant self during the 1921 season, and after a start against the New York Giants on July 9, Vaughn disappeared.

“Jim walked from the pitchers’ box to the clubhouse at the Polo Grounds on Saturday after being belted for successive home runs by Frank Snyder and Phil Douglas and he has not been seen since by Manager Johnny Evers or any other member of the Chicago Cubs,” the Times reported on July 11. The article said that should Hippo Vaughn return to the team, he would be suspended for his unexplained absence.

According to his SABR biography, the Cubs were later ready to reinstate the pitcher, but Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the commissioner of baseball, refused to do so, and suspended Vaughn for the remainder of the season. Interestingly enough, the Times reported in October of that same year that Vaughn was missing again, with his wife having asked the Chicago police to look for him. The same wife, Edna, filed for divorce in 1920, the previous year, only to later drop the proceedings sometime after Edna’s father stabbed Vaughn.

Perhaps this all helps explain the sudden decline of Vaughn, who went from one of the best pitchers in the National League in the 1920 season, to a pitcher with a 6.01 ERA in the 1921 season. He would never appear in Major League Baseball again, despite bouncing around several lower-level leagues.

Arguably, Vaughn is the best left-handed pitcher that the Chicago Cubs organization has ever seen. Between the double no-hitter and his performance both during and leading up to the 1918 World Series (we’ll get to that in more detail in a future article), his on-field feats deserve greater remembrance.