Jett Williams‘s feel for hitting is the tool scouts have most openly questioned during his time in pro ball. Most notably, Eric Longenhagen of FanGraphs tagged just a 30 present value on Williams’s contact ability, on the 20-80 scale. Longenhagen cited a steep swing plane without a lot of adjustability, and that’s difficult to argue with. There’s some evidence, though, that Williams has an exceptionally advanced approach—and thus, that he’s more adaptable than he first appears.

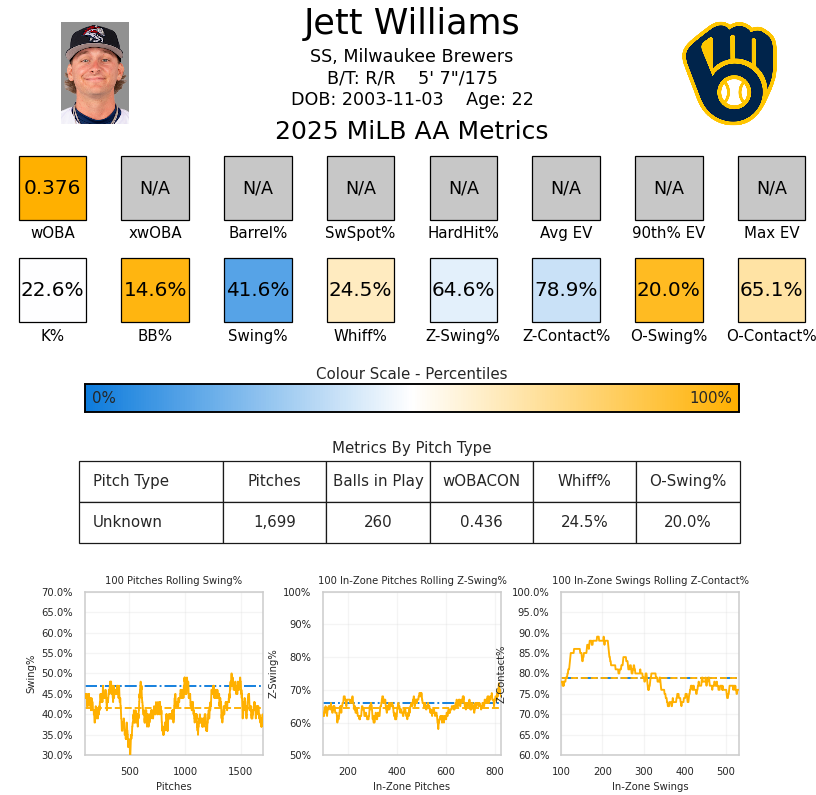

A couple of things stood out immediately on this front. The first is that Williams’s in-zone contact rate was a troubling 78% during his stint in Triple A. The second is his out-of-zone contact rate of 65%, which is well above average. One of Williams’s best traits is his discipline around the strike zone. He rarely chases, but even when he does, he can foul off pitches and extend at-bats. For someone with a stiff swing and poor maneuverability, you would expect his contact rates outside the strike zone to be considerably worse.

Independent analyst Thomas Nestico has an estimated model for pitch locations without Statcast that seems to be a solid approximation of reality. Even at Double A, his in-zone contact rate sagged as the season progressed.

At the same time, we began to see some changes to Williams’s batted-ball profile. He pulled the ball more this season than he had before that, at 47.5%, and he cleared more fences, averaging a home run for every 19 at-bats in Triple A. He traded some contact skills for a more pull-happy approach, but that changed when he got to two strikes.

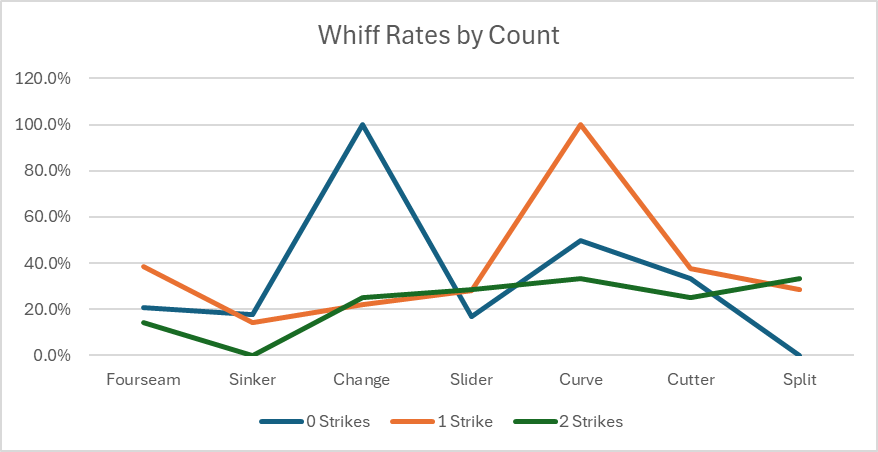

Most hitters are nearly as likely to swing and miss with two strikes as in any other count, with the added likelihood of chasing a pitch offset by the more defensive swings taken by the hitter. Williams, however, whiffs a lot less with two strikes than he does early in the count. The chart below shows the average whiff rate per swing when at zero, one and two strikes:

There are some small samples here, particularly with the curveball and changeup, but the piece I find most intriguing is the swing-and-miss against four-seam fastballs. As Longenhagen mentioned, Williams has a steep swing that he uses to elevate to the pull side; that should create problems with high fastballs. That proved not to be the case with Williams. Nor was he merely fouling off more pitches. He put more balls in play per swing, which suggests that his swing-and-miss concerns might be more of an approach-based decision than a mechanical weakness.

This is reminiscent of a new coach on the Brewers staff. Daniel Vogelbach had the lowest swing rates in the league, happy to work himself into two-strike counts and put the ball in play, but he was looking to do damage in zero- and one-strike counts. Williams might not have Vogelbach’s raw power, but he does have an above-average 90th-percentile exit velocity, and with his heavy pull-side approach, the result could be the same. A better comp, perhaps, would be former second baseman Ian Kinsler, another diminutive but sturdy right-handed hitter who used both a pull-focused approach and good athleticism to carve out a long, impressive career.

The approach will require some maturation, and perhaps there are some mechanical tweaks to allow Williams to find a blend where he can still access the pull-side power but cut down on whiffs early in counts. If he struggles, he could modulate his approach and become a truly contact-oriented hitter, just like Brice Turang did in 2024. With his speed and defensive cover, Williams will have time to find the mold that fits him best in the major leagues; he might have a higher floor than many believe.