Perhaps no other Twin in recent memory saw their prospect stock rise more rapidly than Zebby Matthews. Selected with the 234th pick in the 2022 draft out of Western Carolina and signed for a paltry $125,000, Matthews grew from an afterthought to a top prospect at virtually the speed of light, debuting by mid-August 2024.

Unfortunately, Matthews’s once-bright flame has dimmed in the eyes of some, due to inconsistent performance across 117 major-league innings. His rise was fueled by an uncanny ability to live in the zone, missing bats and not giving up any walks, while drastically improving his fastball velocity. In the majors, his walk rates have nearly tripled from approximately 2.0% in the minors to 6.6%, while his strikeout rates have dropped by roughly eight percentage points.

These decrements in performance, albeit in a relatively small sample, have begun to beg the question: Is Zebby Matthews’s future in the starting rotation or the bullpen?

Zebby Matthews’s Stuff & Pitch Arsenal

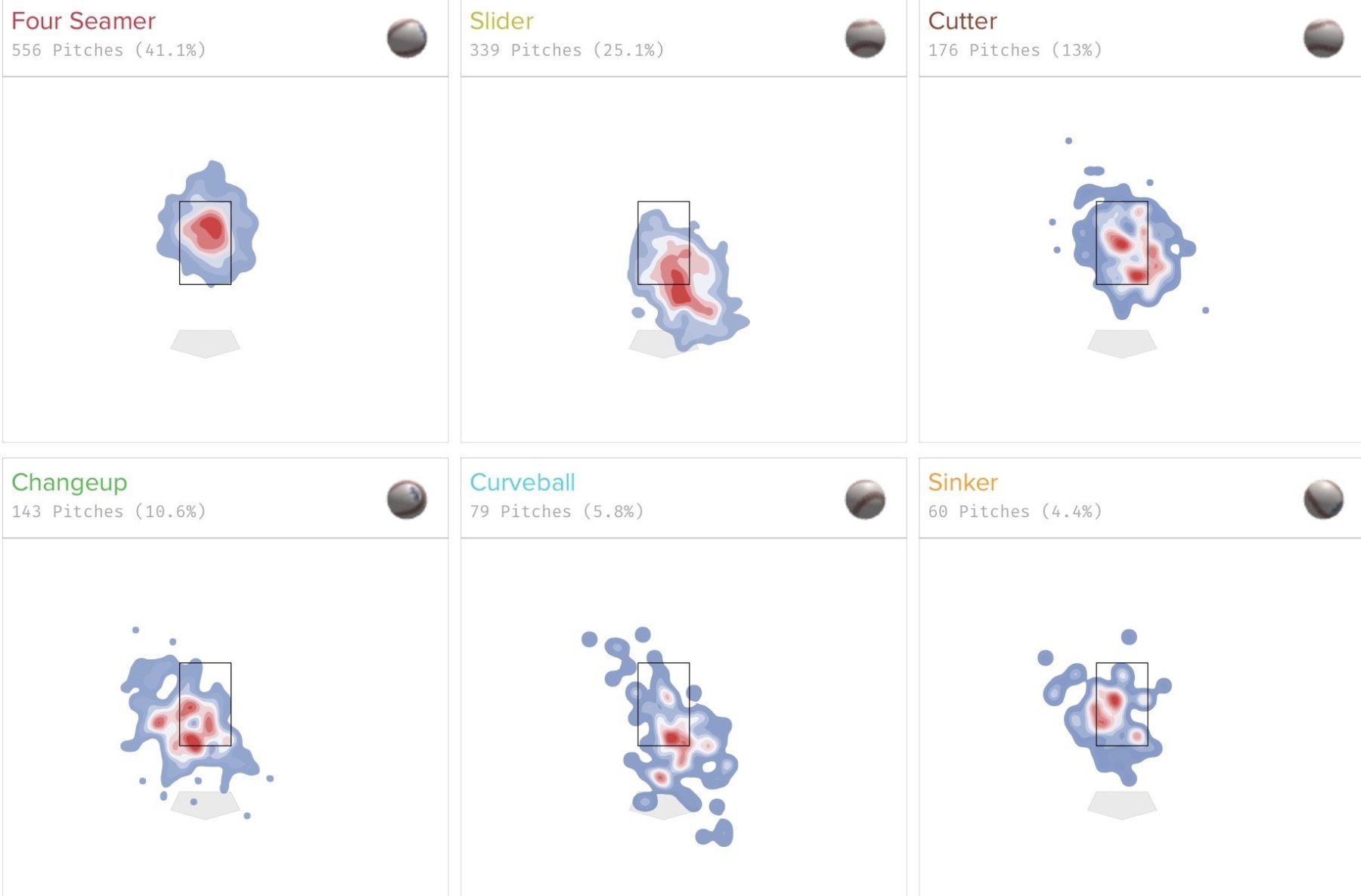

On paper, Matthews boasts a prototypical 2026 starting pitcher repertoire. He primarily relies on his four-seamer and slider, dispatching them against lefties (293 and 140, respectively, in 2025) and righties (263 and 199) at an equal clip. Matthews employs his cutter slightly more often against left-handed hitters (103 vs 73), though the sample size for each is quite small, and virtually only throws his changeup against lefties (104 vs. 39). Sprinkle in the occasional curve and sinker to keep hitters on their toes, and Matthews arsenal is sufficient for a starting pitcher… in theory.

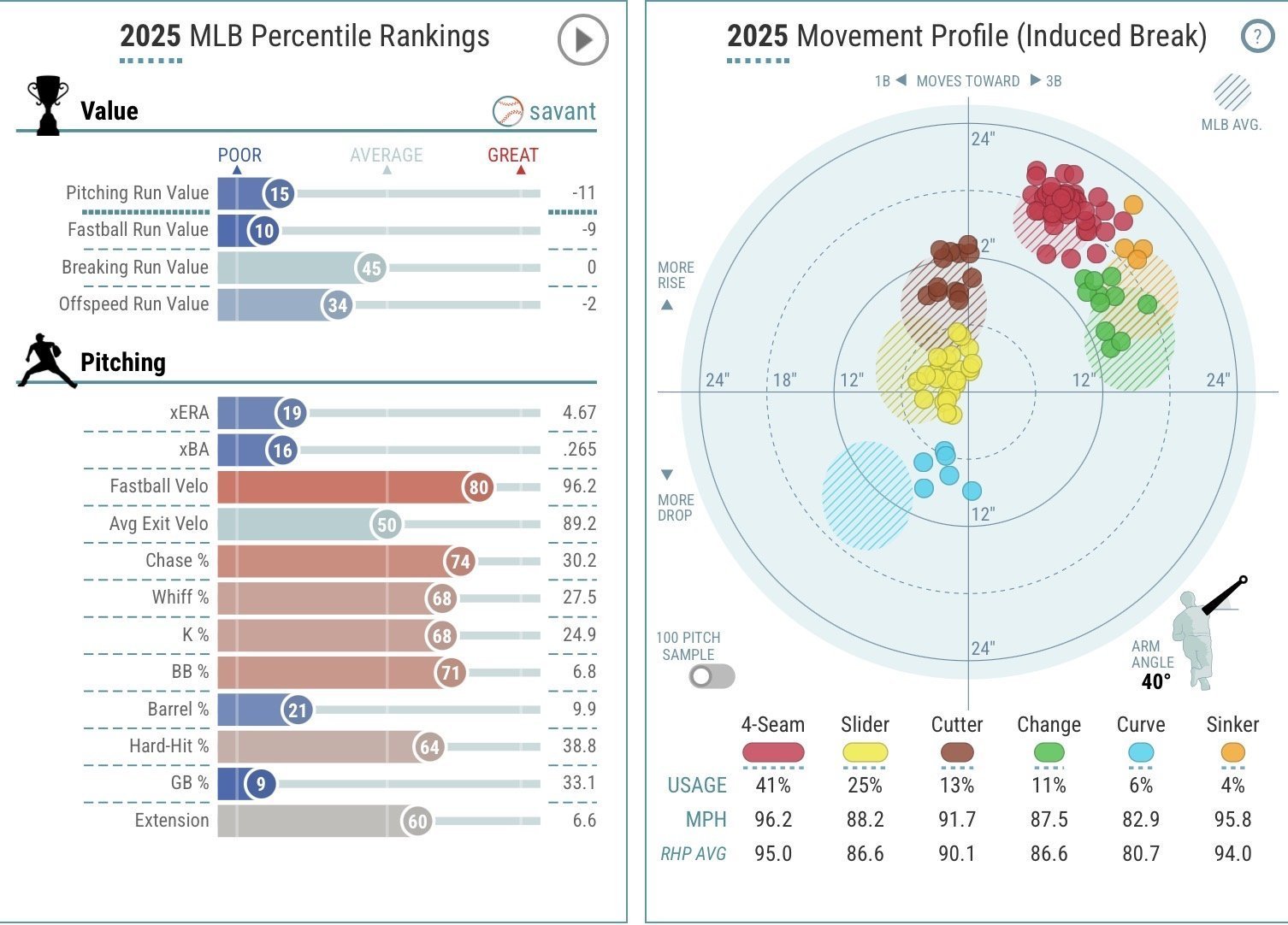

In practice, at least at the MLB-level to date, Matthews really only has one pitch that has performed well: his gyro slider. As shown in the movement profile graph and implied in the slider heat map above, Matthews’s slider features significantly more drop (vertical break) than it does sweep (horizontal break). This is due to the pitch featuring more gyroscopic (think football spiral) spin than side spin. Gyroscopic spin does not influence pitch movement, meaning that the majority of the ball’s movement is simply due to the pull of gravity as it flies through the air.

Across 525 major league offerings, opposing hitters have managed a meager .568 OPS against Matthews’s slider, per FanGraphs, driven by a high-30% whiff rate in combination with a 42% ground ball rate. In essence, when Matthews’s throws his slider there’s high chance that the batter is either going to miss it entirely or pound it into the ground.

The rest of Matthews’s arsenal has been varying degrees of lackluster, even this four-seam fastball, whose crazy velocity creep helped him rapidly rise through the minors. Pitchers can overpower minor league hitting with pure velocity, something Matthews and his mid-90s fastball accomplished. However, the same can’t be said for major league hitting. Generally speaking, if a fastball is going to be a pitcher’s best offering in the majors, it not only needs to possess high velocity readings but also have a movement profile that makes hitting it squarely extremely difficult. MLB hitters can hit straight gas; hitting moving or deceptive gas is much more difficult.

When analyzing the movement profile, or shape, of a fastball, there are two metrics worth considering: induced vertical break and horizontal break. Induced vertical break measures how much the ball drops solely due to its spin, taking gravity out of the equation. If a fastball has a high degree of spin, it will, more often than not, register a higher induced vertical break, meaning it doesn’t drop. This will produce an illusion in the hitter’s brain, making it seem as though the ball is rising. Horizontal break measures how much the ball moves, well, horizontally; if it moves towards the glove side of the pitcher, we say it has ‘cut’, and if it moves towards the hand side, we say it has ‘run’.

Year

Pitch Type

#

# RHB

# LHB

%

MPH

PA

AB

H

1B

2B

3B

HR

SO

BBE

BA

XBA

SLG

XSLG

WOBA

XWOBA

EV

LA

Spin

Ext.

Whiff%

PutAway%

2025

Four Seamer

556

263

293

41.1

96.2

123

112

40

25

8

0

7

30

85

.357

.303

.616

.571

.422

.394

92.7

23

2331

6.6

22.4

19.4

2025

Slider

339

199

140

25.1

88.2

113

107

16

11

2

0

3

50

58

.150

.184

.252

.326

.193

.237

87.5

10

2419

6.4

38.5

24.3

2025

Cutter

176

73

103

13.0

91.7

54

42

14

12

1

0

1

3

40

.333

.318

.429

.482

.405

.414

88.7

15

2494

6.5

24.2

8.6

2025

Changeup

143

39

104

10.6

87.5

32

31

11

7

3

0

1

1

31

.355

.317

.548

.426

.374

.346

86.3

6

1499

6.4

26.3

5.3

2025

Curveball

79

38

41

5.8

82.9

14

14

5

4

1

0

0

2

12

.357

.304

.429

.487

.342

.338

88.9

38

2435

6.3

34.5

10.5

2025

Sinker

60

58

2

4.4

95.8

18

17

8

8

0

0

0

2

16

.471

.264

.471

.320

.415

.255

77.2

6

2317

6.6

7.7

50.0

2024

Four Seamer

307

115

192

42.8

94.9

66

59

17

7

5

0

5

17

42

.288

.262

.627

.592

.417

.394

94.3

19

2230

6.5

17.8

21.3

2024

Slider

186

92

94

25.9

87.2

57

52

16

12

2

0

2

20

32

.308

.251

.462

.400

.363

.318

90.2

11

2349

6.4

37.6

23.5

2024

Cutter

116

62

54

16.2

90.9

30

29

10

7

0

0

3

2

27

.345

.295

.655

.674

.434

.418

87.3

17

2403

6.4

18.2

18.2

2024

Changeup

57

2

55

7.9

85.8

9

9

2

1

1

0

0

0

9

.222

.348

.333

.512

.237

.378

86.6

-5

1550

6.4

31.3

0.0

2024

Curveball

51

9

42

7.1

81.7

15

15

6

4

1

0

1

4

11

.400

.327

.667

.558

.455

.377

87.9

16

2369

6.3

17.4

14.8

Generally, there is a trade-off between a fastball’s induced vertical break and horizontal break; more in one generally leads to less of another. This is where Matthews’s fastballs—both his four-seam and sinker—struggle. The induced vertical break of his four-seamer is 16.6 inches, and his horizontal break is 9.0 inches of run; for his sinker, it is 13.1 inches and 15.2 inches, respectively. These are what are known in the industry as “dead zone” fastballs. Essentially, to the batter’s eye, they appear straight, not having enough induced vertical break to produce the rising illusion and not enough horizontal break to be difficult to square up.

Since Matthews’s made his debut, opponents have produced a .944 OPS (839 pitches) against his four-seamer and a 1.368 OPS (82 pitches) against his sinker. His cutter (.955; 294), changeup (.817; 200), and curve (.931; 130) haven’t fared much better.

However, there are some intriguing data points embedded within Matthews’s splits statistics. Namely, they suggest that he is much better against righties than lefties to the tune of .230 points of OPS (.944 OPS against 278 lefties and .714 OPS against 253 righties) and 4.0% K-BB% (20.2% vs. 16.2%). Which informs…

What Should Zebby Matthews’s Role Be In 2026?

It’s extremely difficult to be an MLB-caliber starting pitcher with only one good pitch. Luckily, carving out a productive career out of the bullpen is relatively achievable. Matthews’s career to date is not all that dissimilar to that of Glen Perkins, Tyler Duffey, and, more recently, Griffin Jax. These were all starting pitchers who experienced great success in the minors before struggling mightily once they reached the majors because their middling repertoires were exposed. However, a shift to the bullpen and increased emphasis on their best pitches transformed them into, at times, devastating backend relievers.

For Matthews to project as a starting pitcher moving forward, he likely needs to add at least one more above-average pitch—perhaps a sweeper or kick-change to complement his gyro slider?—and/or improve the shape of his fastball. Neither is a particularly easy task, though adding a new pitch is significantly more trainable than adding isolated pitch spin/induced vertical break. The Twins have far more metrics available to them, including whether Matthews is more of a natural pronator or supinator, which would influence which pitches would be easier to add, as well as linear and rotational force-velocity data, which would indicate if there is any additional athletic performance meat being left on the bone.

The Twins may continue to employ Matthews as a starter, but, as things stand right now, his profile is much more suitable for a bullpen role.