The Chicago Cubs don’t have to squint to see the future anymore. It’s standing in center field, running down fly balls like they owe him money, and occasionally launching baseballs into the night. Pete Crow-Armstrong is a foundational piece—the kind of player teams spend decades trying to draft, develop, or steal from someone else. Elite defense, real power, and disruptive speed make him a perennial MVP candidate in the National League, even if that ceiling is currently guarded by a certain two-way alien named Shohei Ohtani. A season like the one Crow-Armstrong just had will do that.

A Breakout That Changed the Conversation

In 2025, Crow-Armstrong put together a year that could be a cornerstone’s origin story. He finished with a 109 wRC+, 31 home runs, 35 stolen bases, and 5.4 fWAR. He crossed the plate 91 times, drove in 95 runs, and played center field at a level few in baseball can match. His glove was worth 15 Defensive Runs Saved, placing him among the best defenders in the sport.

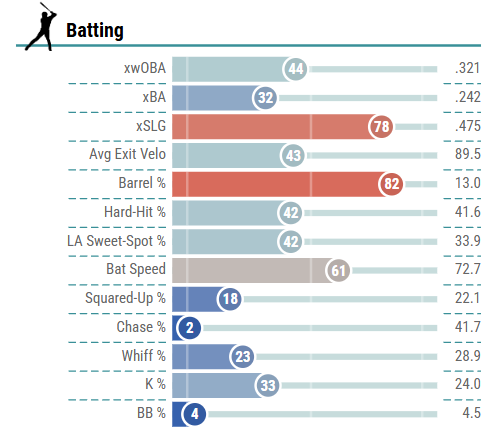

Offensively, the quality of contact backed up the surface stats. Crow-Armstrong ranked in the 82nd percentile in barrel rate at 13% of his batted balls (and 9.1% of his total plate appearances), and his .475 expected slugging percentage landed in the 78th percentile. He may not look like a classic slugger, but he doesn’t need brute strength when he knows how to get the ball in the air and pull it with authority. Pair that with lightning-fast feet and elite instincts, and you get production that stretches across every column of the box score.

The Swing-at-Everything Dilemma

For all the fireworks, there’s a catch: Crow-Armstrong swings at everything. That aggressiveness is baked into his game, and in 2025 it came with some ugly side effects. He posted a 4.5% walk rate, good for the 4th percentile, and chased pitches at a 41.7% clip, worse than all but four other qualifying hitters.

When it works, it’s exhilarating. When it doesn’t, it can look like a hitter trying to swat flies with a sledgehammer. Pitchers adjusted, and the league started leaning into his weaknesses. The result was a tale of two halves that left Cubs fans uneasy.

After crushing the first half with a 131 wRC+, Crow-Armstrong stumbled badly after the All-Star break, posting a 72 wRC+ in the second half. The production drop wasn’t subtle, and it raised a fair question: which version of Crow-Armstrong is the real one?

Why the Second Half Fell Apart

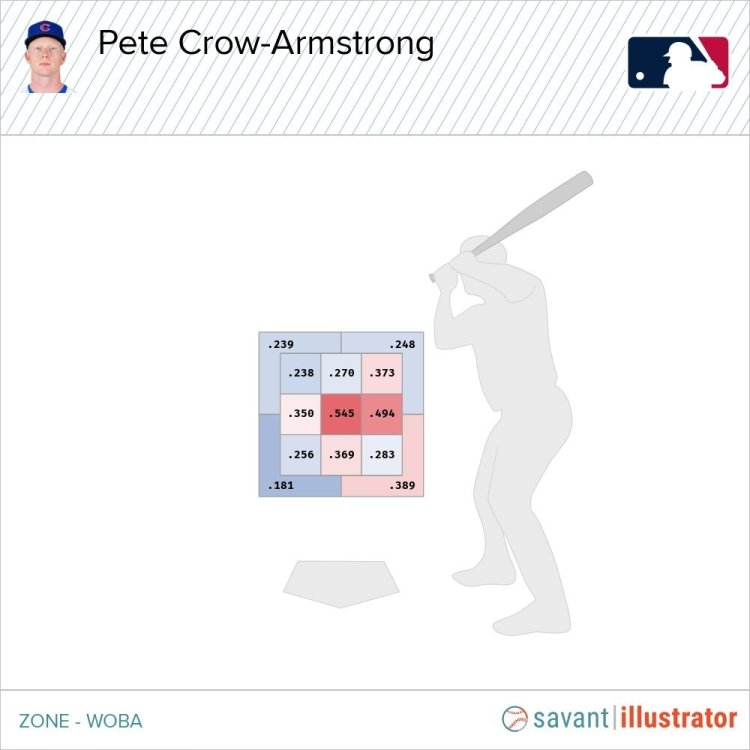

The answer isn’t a single smoking gun, but a handful of factors that piled up quickly. Crow-Armstrong is particularly vulnerable to pitches up in the zone—especially fastballs. When you look at his wOBA by pitch location, the elevated areas are where the damage turns into self-inflicted wounds. Pitchers found that soft spot and kept going back to it.

Luck also played a role. In the first half, his home run-per-fly ball rate sat at 17.6%. After the break, it cratered to 6%. It’s fair to wonder if the early number was simply too hot to sustain.

As Elliot Baas of Rotoballer.com noted, Crow-Armstrong’s average launch angle dipped month by month, which likely contributed to the power outage. Line drives turned into grounders, and fly balls lost their carry. Interestingly, some of his plate discipline indicators actually improved in the second half. His chase rate dropped to 36.9%, and his swinging strike rate improved from 16.5% to 15.2%. In trying to rein himself in, he may have dulled the very edge that made him so dangerous early on—but that reining-in was certainly needed, so it’s discouraging to admit that it didn’t work.

What the Future Still Looks Like

Even with the warts, Crow-Armstrong remains an immensely valuable player. The defense is as real as it gets, and at 23 years old, he should have several more seasons as an elite center fielder, assuming good health. On the bases, his speed gives him room to push higher. With a green light (and a better OBP), 40 to 45 steal attempts aren’t out of the question, making 30 to 35 stolen bases a reasonable expectation.

Offensively, the underlying numbers offer reassurance. His .323 wOBA was nearly identical to his .321 expected wOBA, suggesting his overall line wasn’t built on good bounces. Repeating a 30-homer season may be a tall ask, but settling into a 20-homer, 30-steal profile with a yearly wRC+ between 100 and 110 is well within reach. That version of Crow-Armstrong can flirt with 5.0 fWAR on a regular basis, with more upside if he ever adds even modest gains in plate discipline.

Crow-Armstrong isn’t a finished product, but he doesn’t need to be. He’s already a building block—a player who impacts games with his bat, glove, and legs, and one the Cubs can confidently build around as the next era takes shape.