Even at a young age, Paul Guillie had a vision of what his life’s calling might be.

Alongside his duties lining baseball diamonds and cutting fields for Jefferson Parish Recreation Department, a young Guillie was already officiating JPRD baseball games—calling contests for teams two to three years younger, then turning around to umpire games featuring players his own age. The foundation was being laid long before he realized it.

Guillie later became an All-District second baseman at East Jefferson High School under coach Barry Poché. The Warriors reached the state quarterfinals in 1977. During his prep career, an exchange with an umpire would alter his trajectory forever. After Guillie questioned a call, the umpire responded, “If you think you can do this…” That moment planted a seed—one that soon grew into a passion.

As a player, Guillie went on to play for Delgado under legendary coach Rags Scheuermann from 1979–80, then finished his collegiate playing career at Southeastern Louisiana in 1982 as a first baseman.

At the time, college baseball conducted fall scrimmages between competing schools, offering an entry point for aspiring umpires to gain experience at the collegiate level. It was there that Guillie caught the bug.

In February 1984, Guillie worked as part of a two-man umpiring crew for a game between UNO and South Carolina—coached by two veterans of the profession. Ron Maestri was in his 13th season at UNO, while June Raines had spent 20 years at the helm of the Gamecocks.

“I worked that game with Ron Scharff,” Guillie recalled. “He was a minor league umpire. I actually did college games before I umpired high school.”

Later that spring, Guillie was assigned to another UNO contest—this one stacked with future Major League talent. Mississippi State arrived at the Lakefront with Ron Polk, a two-time National Coach of the Year, and a roster that included Will Clark, Rafael Palmeiro, Bobby Thigpen, Jeff Brantley, and Jesuit product Tim Parenton.

UNO countered with Wally Whitehurst, Jimmy Bullinger, Stuart Weidie, Tommy Schwaner, and Barry Raziano. The Privateers out-hit the Bulldogs 17–14 and won a 20–13 slugfest—another formative moment in Guillie’s rapid ascent.

Still just 24 years old, Guillie was later assigned to umpire the Tulane–UNO Pelican Cup game at Privateer Park in the spring of 1984.

“Most of the veteran umpires I worked with were 15 to 18 years older than me,” Guillie laughed. “Privateer Park was packed to the rafters. Fans were even allowed to sit along the foul territory behind ropes.”

Tulane’s lineup featured Dan Wagner, Tommy Matthews, Glen Fourmaux, and current Delgado head coach Joe Scheuermann, while the pitching staff included Kevin Mmahat and Marc Desjardins.

The following season, Guillie worked all three Pelican Cup games—a notable achievement, as umpiring crews were recommended by opposing coaches Ron Maestri and Joe Brockhoff.

“Paul was one of the guys who broke the barrier and allowed other umpires from Louisiana to get to that level,” Maestri said. “He was the consummate professional. He looked like an umpire. He set the bar high.”

Over his career, Guillie worked 19 SEC Tournaments, 19 NCAA regional tournaments, and 14 Super Regionals before earning his first College World Series assignment. In total, he was selected to the SEC Tournament 21 times over a 31-season career.

“A lot goes into selecting the College World Series crew,” Guillie explained. “Coaches evaluate you, tournament directors evaluate you, crew chiefs and national coordinators give their input. Your reward for diligent, hard work is getting invited back.”

Guillie umpired four College World Series—2001, 2004, 2006, and 2010—the last as crew chief.

During the 2001 Series, Tulane—coached by Rick Jones—faced Nebraska. Guillie was working second base when a Nebraska batter hit a home run that sparked controversy over potential fan interference.

“I called it a home run,” Guillie recalled. “Rick thought there was interference.”

Replay later confirmed Guillie’s call was correct.

In another Omaha moment, a frustrated coach attempted to shift his team’s focus by intentionally getting ejected and asked Guillie to throw him out.

“If I have to be here for this,” Guillie replied, “so do you.”

In November 2015, Guillie officiated the Premier12 tournament in Tokyo, an international effort aimed at growing baseball’s Olympic presence. The event featured teams from the United States, Japan, Korea, and Mexico.

“I was able to achieve that honor through the support of international umpire Gus Rodriguez,” Guillie said.

One unforgettable moment came when he was at second base as Shohei Ohtani stepped to the plate.

“He pitched and was the DH,” Guillie said with a smile.

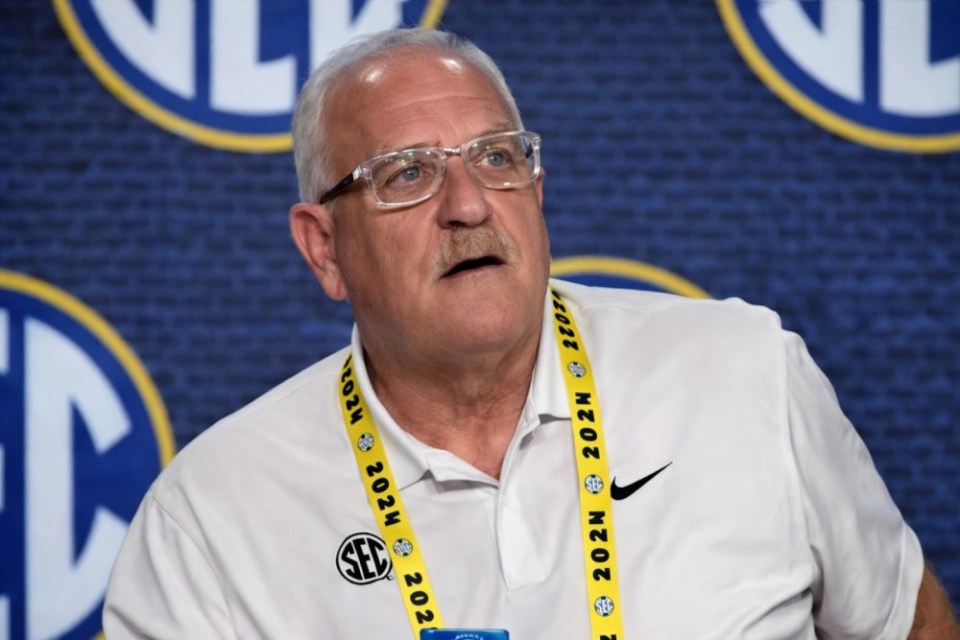

Following his retirement from on-field umpiring, Guillie transitioned into administration, serving as the SEC coordinator of umpiring assignments. He later added the Atlantic Sun, Ohio Valley, Sun Belt, Southland, and Southern Conferences—overseeing more than 400 umpires.

“There are tangibles and intangibles,” Guillie said. “Athleticism, mechanics, fitness, rules knowledge—but also that ‘it’ factor. You have to know when to insert yourself and when not to.”

Guillie has also played a key role in advancing officiating technology. Under his guidance, the SEC implemented electronic pitch recognition systems as a training tool, helping umpires improve consistency—technology later adopted by other conferences and the NCAA.

With Major League Baseball implementing automated ball-strike challenge systems in 2026, Guillie believes college baseball could follow within five to six years.

“If you can get things right, it’s worth it,” he said. “It doesn’t remove the human element. It eliminates egregious errors.”

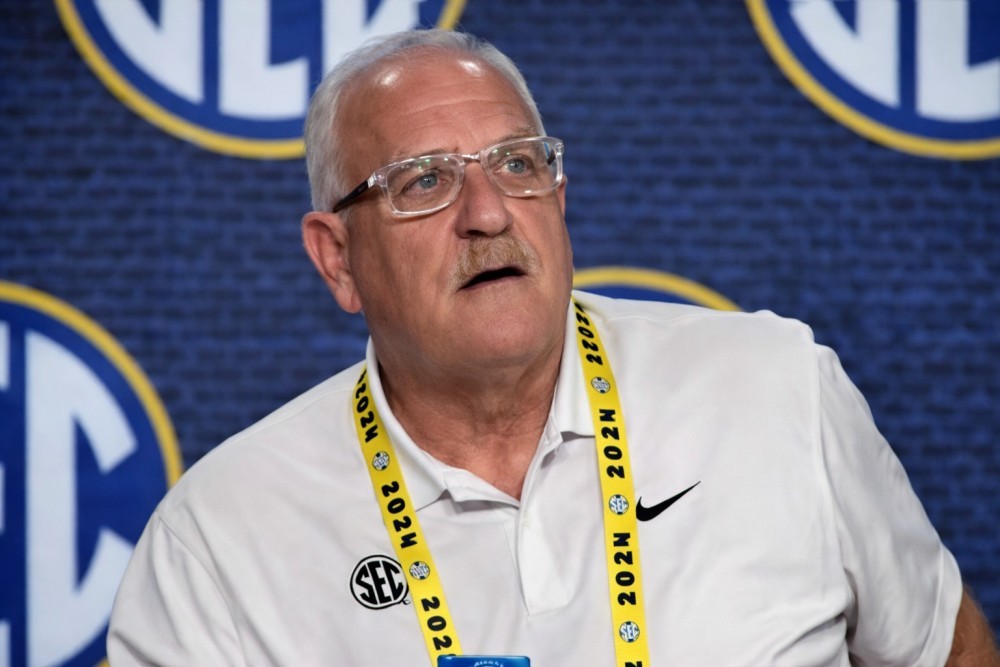

On February 12, Guillie will travel to Overland Park, Kansas, to be inducted into the National College Baseball Hall of Fame—becoming just the third New Orleans native to receive the honor, joining Will Clark and legendary coach Rod Dedeaux. He is also only the 13th umpire ever inducted.

For Guillie, the motivation was never money or fame.

“I just wanted everyone to have a fair sense of play,” he said. “I thought I could do that.”

And now, baseball’s highest collegiate honor agrees.