In the latest twist in the Chicago Cubs’ lawsuit against a neighbor that sells rooftop seats to watch Cubs games, Wrigley View Rooftop says the Cubs “do nothing to prevent” whom the company calls “overserved patrons” from “micturating upon,” vomiting on, littering on, trespassing and vandalizing its property on 1050 West Waveland Avenue.

The sharp rebuke is part of Wrigley View Rooftop’s 37-page answer to the Cubs’ amended complaint. Attorneys Matthew De Preter and J. Timothy Cerney drafted the answer and filed it in an Illinois federal district court last week.

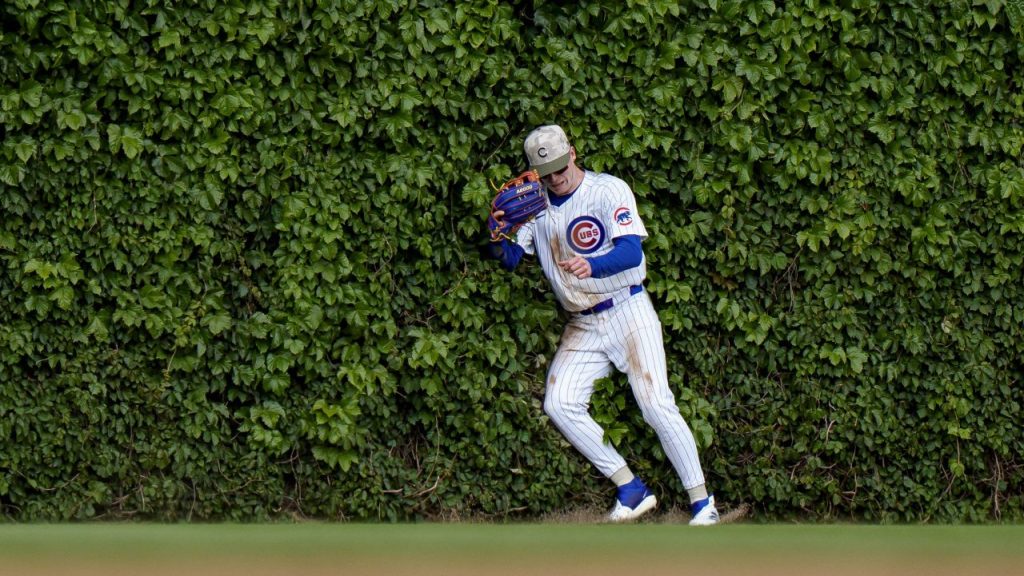

The Cubs sued Wrigley View Rooftop and its founder and president, Aidan Dunican, last year for misappropriation, false advertising, unjust enrichment, unfair competition and unauthorized use of Cubs’ trademarks. Established in 2000, Wrigley View Rooftop is right across the street from the famed ballpark. In selling seat packages that include “bountiful buffet and beverage service through the 7th inning,” the company boasts it is “in the heart of Wrigleyville” and “just steps beyond the left field ivy.”

In 2004, Wrigley View Rooftop was one of several rooftop companies that reached litigation settlements with the Cubs. Those companies agreed to share revenue with the team and the settlements expired in 2023.

The Cubs extended settlements with rooftop companies except Wrigley View Rooftop, which has continued to sell tickets without the Cubs’ blessing. Wrigley View Rooftop insists the Cubs demanded an “unconscionable” licensing agreement in a proposed extension. The answer says the team required an increased share of gross revenues from 17% to 40%, which Wrigley View Rooftop terms an “unacceptable demand” and “a ruse to ensure [the Cubs] would proceed with plans to devalue Defendants’ property and strongarm Defendants into selling to [the Cubs].”

Wrigley View Rooftop also claims it removed marks associated with the Cubs from its website and added a disclaimer stating, “Wrigley View Rooftop is not affiliated with, nor is it endorsed by Major League Baseball or the Chicago Cubs.” In addition, Wrigley View Rooftop says the Cubs erected scaffolding and barriers to try to block the view from 1050 West Waveland Avenue.

A key theme raised by Wrigley View Rooftop is the company’s assertion that the Cubs have “no right to control enjoyment of others’ private property.” The company suggests the Cubs are mistaken about the geographic scope of their rights, which the answer insists do not extend into 1050 West Waveland Avenue. Wrigley View Rooftop asserts it is “properly licensed by the City of Chicago to operate on their private property” and the Cubs can neither trespass into nor dictate how Wrigley View Rooftop uses the property.

The answer also portrays the Cubs as unneighborly. Although Cubs games are (obviously) the key draw for Wrigley View Rooftop’s business model, the team is nonetheless accused of having “never compensated” Wrigley View Rooftop for alleged property damage resulting from “the throngs of people drawn to Wrigley Field.” Wrigley View Rooftop goes so far as to say its property is “nearly unlivable,” with “extraordinarily noisy activity throughout the night after Cubs games that make sleeping . . . nearly unbearable.”

Wrigley View Rooftop also contends the Cubs should accept the realities of playing in a ballpark observable from different vantage points in adjacent buildings. The team, which the answer notes “has sold images of the view from within Wrigley Field as including a view of the surrounding buildings,” is depicted as only having itself to blame for using an open air ballpark that permits non-paying people to view live games from surrounding buildings.

To that point, the Cubs could use their “control over the structure of Wrigley Field” to erect “higher fencing” and other modifications to block viewpoints. The answer even claims the Cubs “chose not to play baseball games in a domed stadium.” The idea of the Cubs moving from Wrigley Field, which was built in 1914 and has been designated a National Historic Landmark, to a domed stadium might seem absurd. However, 40 years ago, there was a proposal for a domed stadium in Chicago to house the Cubs, White Sox and Bears.

U.S. District Judge Sharon Johnson Coleman is presiding over the case. In January, she denied Wrigley View Rooftop’s motion to dismiss on grounds that an arbitration provision in a prior settlement agreement is an “improper mechanism” for dismissing the lawsuit. The Cubs assert the team holds an undisputed property right to Cubs games and there is no public right to watch a Cubs game in person or by broadcast.