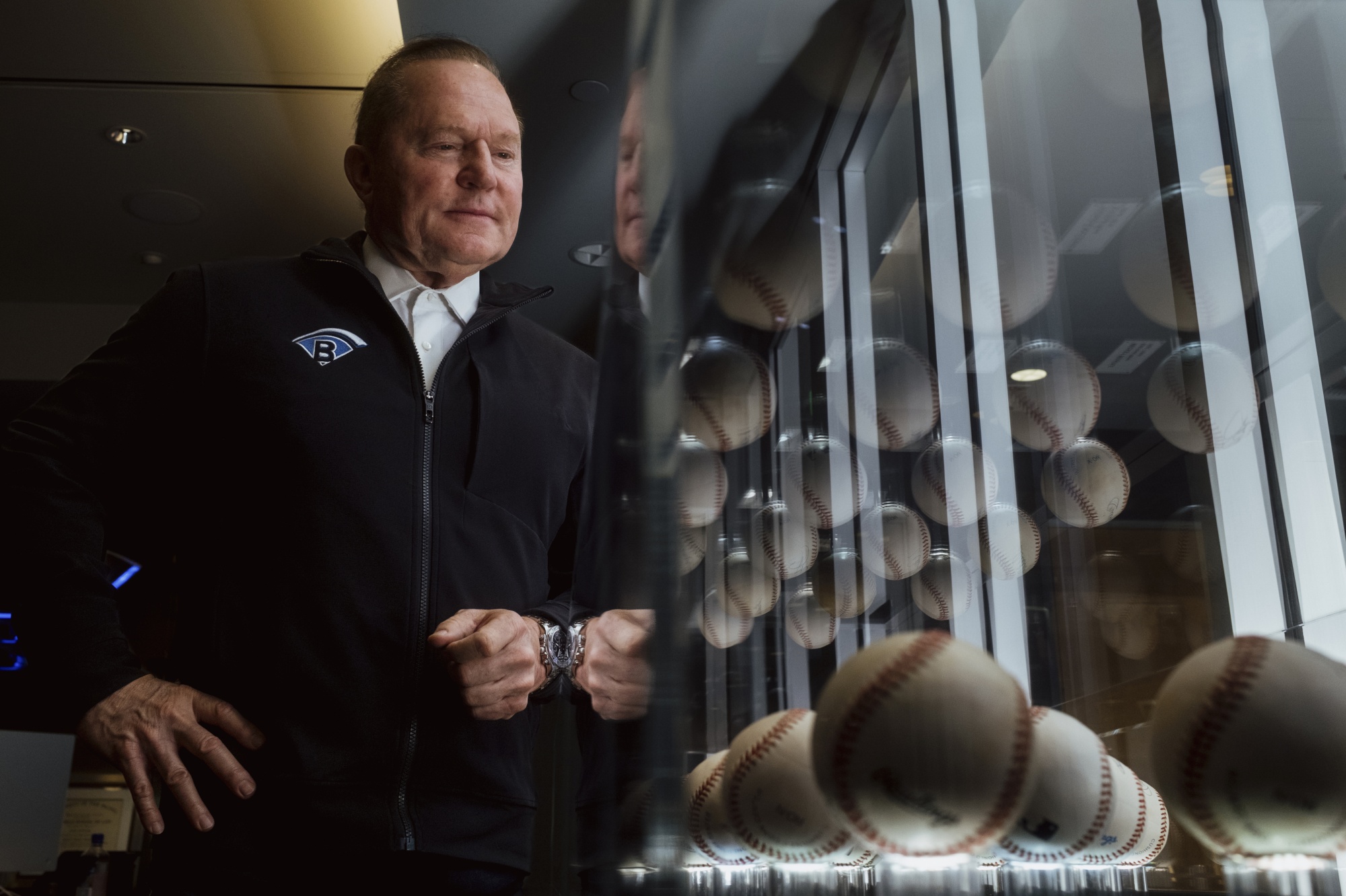

Baseball agent Scott Boras at his firm’s Southern California headquarters. He negotiated contracts worth $1.7 billion for his clients this offseason. Photographer: Mark Abramson/Bloomberg Agent Scott Boras had another record offseason, reigniting calls for a salary cap — and threats of a lockout. By Dylan SloanIra BoudwayKyle Kim April 11, 2025

Baseball agent Scott Boras at his firm’s Southern California headquarters. He negotiated contracts worth $1.7 billion for his clients this offseason. Photographer: Mark Abramson/Bloomberg Agent Scott Boras had another record offseason, reigniting calls for a salary cap — and threats of a lockout. By Dylan SloanIra BoudwayKyle Kim April 11, 2025

On a Friday in December, baseball agent Scott Boras and his client Juan Soto paid a visit to New York Mets owner Steve Cohen at his home in Delray Beach, Florida. Soto, a 26-year-old lefty slugger, was the most sought-after free agent in baseball. It was the second meeting of the offseason between Cohen and Soto, who was also considering offers from the New York Yankees, Boston Red Sox, Toronto Blue Jays and Los Angeles Dodgers.

In Delray, Boras peppered Cohen with questions. He posed different scenarios that might arise if Soto became a Met. Could the team surround him with enough talent? By the time it was over, the 68-year-old hedge fund manager was convinced he had little chance of landing Soto. Later, he’d call it one his worst meetings ever, no small thing for someone who oversees more than $35 billion in assets and endured a seven-year federal investigation into allegations of insider-trading at his former firm.

For Boras, it was standard operating procedure. The 72-year-old has been making owners squirm since he began representing players four decades ago. He wanted Soto to see Cohen go off-script. “I don’t want a canned answer,” he says during an hourlong interview in March. “Sometimes you need to know how they react and what they say they’re going to do when they’re challenged.”

Two days later, Soto decided to join the Mets on a 15-year, $765 million contract, the largest in the history of professional sports. It was the showpiece in a blockbuster offseason for Boras, who also secured $210 million over six years for Corbin Burnes in Arizona; $182 million over five years for Blake Snell with the Dodgers; and $120 million over three years for Alex Bregman in Boston.

By Opening Day, Boras had negotiated more than a dozen contracts with a combined lifetime value of nearly $1.7 billion, the largest haul for a single agent in one offseason, according to data from Baseball Prospectus. It also pushed Boras past the $10 billion mark in total free-agent deals for his clients since the publication began tracking, making him easily the most successful and influential agent in baseball, and arguably, in US sports. If you include every contract in his more than 40 years in the business, the total rises to nearly $15 billion.

Boras Contracts Overshadow Industry Competitors

MLB free agent contracts signed each season, by agency

Sources: Baseball Prospectus, Bloomberg reporting

Note: International contracts excluded.

In that time, Boras has built a reputation as a fierce advocate for players, known for toting binders full of stats into negotiations to substantiate his demands, and as a pain in the side of owners, known for searching out loopholes in the league’s collective bargaining agreement and pushing negotiations to the 11th hour. He’s been called an “extortionist” and the “most hated man in baseball”. For some fans, he’s an emblem of the creeping influence of money in the sport, a scapegoat for everything from the rising cost of hot dogs to ads on jerseys.

With his record-setting offseason, Boras, and his clients, are again at the center of a debate about the lopsided economics of baseball. The Dodgers, Mets, Yankees and the Philadelphia Phillies are each set to pay more than $300 million for their Major League rosters this year, while the 10 teams at the bottom of the table are slated to spend less than half that. Perhaps not coincidentally, only one team with a payroll in the bottom third has made it to the World Series in the last decade.

“I’m sympathetic to fans in smaller markets who go into the season feeling they don’t have a chance in the world to win,” league Commissioner Rob Manfred told the New York Times earlier this month. “If people don’t believe there’s competition, you’ve got a product problem, an existential problem for your business.”

Sign up for Bloomberg’s Business of Sports newsletter

For owners, the answer appears to be a salary cap, a hard limit on player compensation such as those already in place in the National Football League and National Basketball Association. With the current collective bargaining agreement between players and the league set to expire at the end of next year, Manfred and a handful of owners have already begun the push for one in baseball, a move the players’ union has successfully resisted for decades.

The brewing conflict threatens to bring baseball to a halt, with many in the industry expecting owners to lock players out ahead of the 2027 season. The last big fight between players and owners over a salary cap, in 1994, led to the longest work stoppage in the game’s history, the cancellation of that year’s World Series and damage to the league’s reputation that took decades to mend.

For now, though, the game goes on. On a Wednesday evening in early April, Boras settles into his seat at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles about 40 minutes before first pitch for a game against the Atlanta Braves. As on most gamedays, he’s already been at the ballpark for hours, watching the East Coast games in a private suite along with a few staffers from his agency, the Boras Corporation. During the season, the stadium serves as a makeshift office for the company, whose headquarters are about 50 miles south.

Wearing a blue oxford, dark wash jeans and a navy Boras Corp. quarter-zip, Boras carries a 24-ounce Starbucks iced tea to his front-row seat, 10 down from home plate on the third-base side. Former Wheel of Fortune host Pat Sajak leans over to say hello from a few seats over. Boras has been a regular at Dodger Stadium for nearly three decades. As the officials huddle before the players take the field, the second-base ump flashes a wave.

Snell is pitching for the Dodgers. It’s his second start after signing the $182 million deal Boras negotiated in November. As the players finish their warmups, Boras’ phone lights up. It’s Cohen. Pete Alonso, another Boras client, has just hit a three-run homer in the eighth inning to bring the Mets level in Miami. “That was cool,” reads Cohen’s text.

Boras says he and Cohen keep in touch regularly – despite a tortured back-and-forth over Alonso’s two-year, $54 million deal signed in February. “This has been an exhausting conversation,” Cohen told the crowd at an event for Mets fans as the negotiations dragged on. “Soto was tough. This is worse.” In the end, Cohen later told longtime Mets radio announcer Howie Rose, he and Alonso hashed out their differences as Boras sat by wordlessly. (Boras says he stayed quiet deliberately to allow the two to have an open dialogue.)

Things are warmer now. “Steve is an owner that calls all the time to ask questions,” says Boras.

Their chumminess is a knock-on effect of MLB’s lopsided economics. With a net worth of $17.3 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, Cohen is the richest owner in the league by a wide margin. A lifelong Mets fan, he paid $2.4 billion for the team in 2020 and has shown a willingness to spend whatever it takes to bring the franchise its first title since 1986.

Boras watches his client, Juan Soto, during a game in Anaheim, California, in 2024. After the season, Soto signed a record 15-year, $765 million contract with the Mets. Photographer: Brandon Sloter/Getty Images

With Soto, Cohen set a new standard not only for pay but for perks, agreeing to a $75 million signing bonus, a no-trade clause, an opt-out after five years, a luxury suite at Citi Field for home games, and a guarantee that Soto could keep his uniform number (22). The deal brought joy in Queens and shock and dismay in the Bronx, where Soto helped the Yankees to the World Series last season.

Even the Yankees, long one of the league’s top spenders, are beginning to feel left behind. “It’s difficult for most of us owners to be able to do the kind of things that they’re doing,” Yankees owner Hal Steinbrenner said of the Dodgers in January, a couple of months after they defeated his team in the Series.

A History of Swelling Salaries

Scott Boras is behind many of baseball’s biggest free-agent deals since 1991

Sources: Baseball Prospectus, Bloomberg reporting

Note: International contracts excluded. Photos: Getty

In an effort to cool the free agent market, the league has tried increasing luxury taxes for teams that exceed payroll thresholds. In 2022, the league added a tier for repeat offenders, nicknamed the “Cohen tax,” that taxes teams at a marginal rate of 110%. So far it hasn’t worked. Last season, according to a memo obtained by ESPN, nine teams paid at least some luxury tax, with the Dodgers, Mets and Yankees all hitting the maximum rate.

The next logical step, at least in the eyes of many team owners, is to limit pay. “Owners are doing a lot of scheming right now about how to get a salary cap,” says Andrew Zimbalist, a sports economist at Smith College. “They’re thinking that the only way that they could possibly get it is by doing a lockout that lasts really long, maybe a year or even longer.”

As Boras sees it, the uproar over pay is a convenient way for league management to distract from its own unforced errors in failing to maximize revenue. “We have great attendance. We’re offering you content that is unbelievable,” he says. “So why are you not optimizing it like other sports executives are?”

TV deals, long a reliable source of billions in annual revenue for MLB, have suffered since the pandemic. Cash flows from regional sports networks, which carry local teams’ games over cable, have withered as rampant cord-cutting has forced some into bankruptcy. And in February, ESPN, the league’s biggest national broadcast partner, announced that it had decided to opt out of the final three years of its rights deal, making this season its last and leaving the league to look elsewhere for $550 million in annual revenue.

Unlike peers such as the NBA, which used the growing appetite for streaming content to lock in high-value, long-term media deals, Boras says MLB both undersold its product and fumbled away hundreds of millions by granting ESPN the option to leave early.

“Why did you allow an opt-out in that?” he asks, noting that he might be MLB’s foremost expert on such clauses: he practically invented them.

A spokesperson for the league declined to comment.

Boras has little patience for the complaints of small-market owners, who, as he sees it, shouldn’t expect a level playing field after paying small-market prices for their teams. If the league wants more competitive balance, he says, it should set up a system to starve the owners of underperforming teams of revenue-sharing payments. Those that repeatedly miss the playoffs, have poor attendance or fail to invest in facilities, he argues, shouldn’t be subsidized by the rest of the league. “We have got a number of franchises that need to be reviewed,” he says.

It’s a radical, self-serving proposition with a miniscule shot at becoming reality. At the same time, it demonstrates both Boras’ aggressive negotiating style and his abiding passion for the game. His bedrock convictions, as becomes clear over the course of spending a few hours with him, are that baseball is great and its best players always deserve more.

Growing up on a dairy farm in California’s Central Valley, Boras used to hand-wire a transistor radio into an oversized ballcap so he could listen to Giants and Athletics broadcasts while driving the tractor. He played four seasons of minor league baseball, rising as high as double-A, before knee injuries cut his career short in 1977. “I made the Florida State League All-Star team and was hitting .290 and life was going good,” he says.

Baseball has made Boras a wealthy man. He takes a standard 5% of all free agent deals, meaning his agency has taken in at least $400 million in pre-tax commissions since 1991, according to Baseball Prospectus data, and is guaranteed another $130 million over the next 15 years on top of that.

Boras doesn’t sit on his profits, though. He’s long touted his staff of around 160, including a global network of scouts and a sports psychologist, and his Newport Beach training facility for players. And although he’s been approached about selling his business, Boras says he’s not interested in giving up control. “I’m not a finance guy. I’m a baseball guy,” he says. “I want to beat the game. And the way I do it is through the players I represent.”

After the bottom of the second inning at Dodger Stadium, Atlanta is up 5-2. Snell is struggling. Boras leans over. “I bet you six or seven runs will win this game,” he says. Boras has propped an iPad against the netting to keep an eye on the Yankees, who are playing at home against the Arizona Diamondbacks.

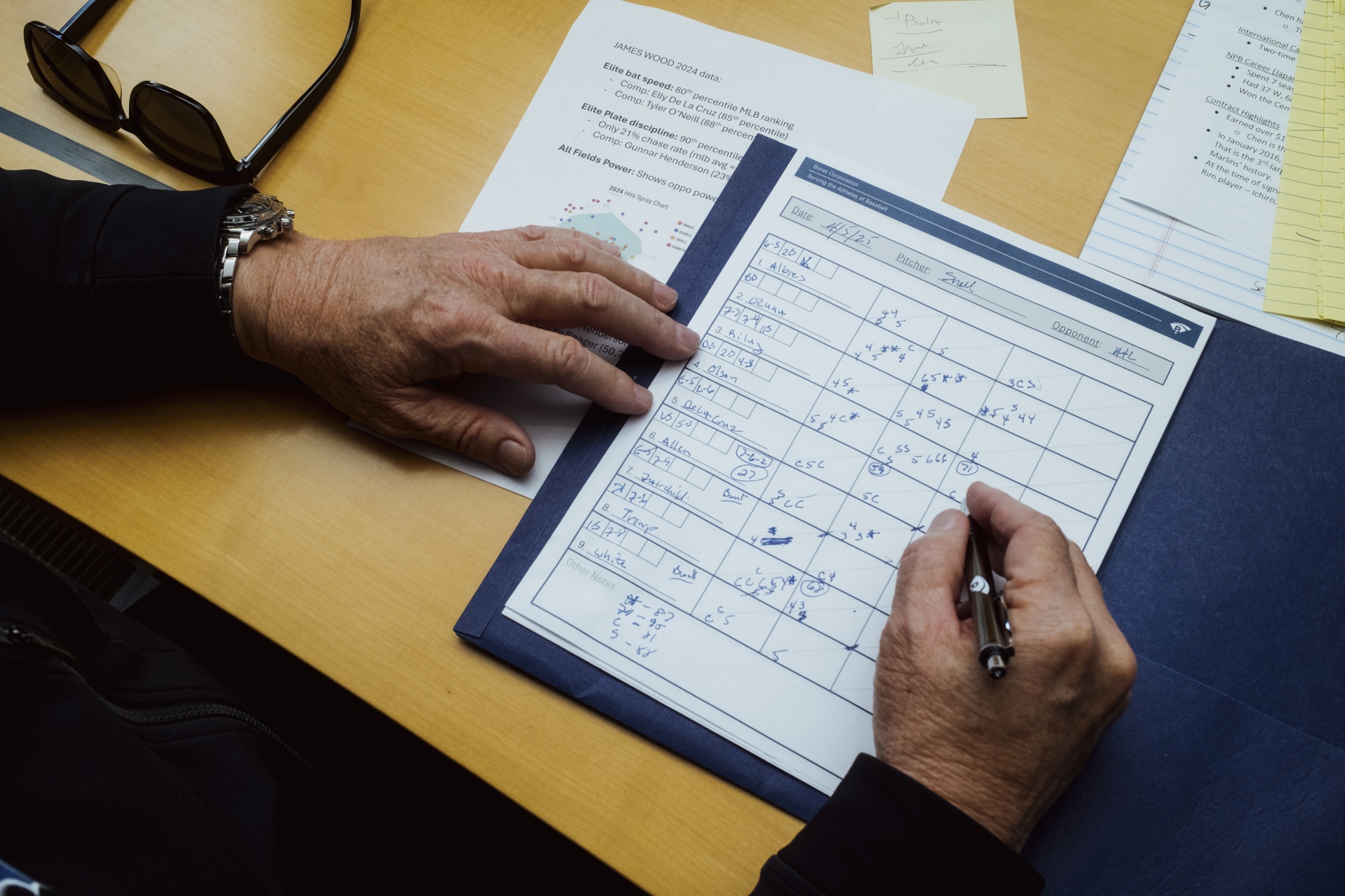

Two seats to his right, his analysts are tracking Diamondbacks ace Zac Gallen, another client, and analyzing his pitch sequences. In Boras’ lap is a blue folder filled with custom score sheets he uses to track his clients’ pitches by hand.

When Boras watches one of his clients on the mound, he tracks every pitch by hand. Photographer: Mark Abramson/Bloomberg

Boras’ attention to detail is legendary: He gets an auto-generated email every half-hour with live stats for every one of his clients currently on the field, and has at least one employee watching every single game all season long to alert him in case he needs to tune in. After each night’s slate of games, he reviews a condensed file of every single pitch, at-bat and defensive play by his clients.

Boras sends multi-paragraph texts to his players after many of their games, giving them feedback on their performance and offering advice. During the Dodgers game, he uses a translation app to text Cincinnati Reds shortstop Elly De La Cruz in Spanish; Elly texts him back – “Thx big dog,” plus fire emojis.

In the top of the fifth inning, Boras reaches into his briefcase. “Want a prune?” he asks, pulling out a bag. “Perfect middle-of-the-game meal.”

At 72, Boras maintains his best years are ahead of him. “I got another 30 years or so of this and I’m going to keep operating,” he says. He’s turned down offers to become a general manager at a team or take a stake in ownership: “I would never represent someone one day and turn around and negotiate against them the next,” he says. The long-term plan is to pass Boras Corp. down through a family trust. “I’ve built a company that will go beyond me,” he says, “We’re always going to do this.”

By the ninth inning, the Dodgers have pulled even at 5-5, and Shohei Ohtani comes to the plate. Prior to Soto’s Mets deal, the Japanese superstar held the record for largest in baseball history with a 10-year, $700 million contract signed in 2023 that included $680 million in deferred payments. By league accounting, that structure made the deal worth $460 million in present value.

Ohtani isn’t one of Boras’ clients, though not for lack of trying. Before Ohtani came to the US in 2018, Boras flew to Japan five times and met his parents in an effort to land him, only to lose out to CAA’s Nez Balelo. During negotiations over Soto, Boras says, team owners set Ohtani’s deal with the Dodgers as a benchmark. If Ohtani – an elite pitcher and a Soto-level slugger, as well as a household name in Japan and the US – got $460 million, they argued, surely Soto should get less.

Boras insisted on a different valuation. “We have a different algorithm and a different method of evaluating players because it includes so much about who they are, their learning aptitude and their psychology,” he says. At every meeting between Soto and his suitors, Boras had his client recount, pitch-by-pitch, his game-clinching at-bat against the Cleveland Guardians in last year’s playoffs. As Soto described how, after six pitches, he got the one he wanted, everybody in the room “sat there ablaze,” says Boras. “Then you understood Juan Soto.” In the end, Soto got more than Ohtani, whose deal, in retrospect, looks like a bargain.

A few yards away from Boras, Ohtani, the one that got away, connects on an 89-mile per hour changeup from Braves closer Raisel Iglesias and sends it sailing toward centerfield. “There’s your sixth run,” says Boras, already standing to leave as the ball clears the fence, giving the Dodgers a walk-off win.

(Updates with additional details about the Cohen-Alonso negotiation.)

Edited by Janet PaskinAlex TribouKristine Owram Photo editor by Marie Monteleone