Dave Parker, the former MVP outfielder and recent Hall of Fame inductee, died on Saturday. He was 74, and had been battling Parkinson’s Disease for some time.

Parker, who had one of the best nicknames in baseball history, the Cobra, is best known for his time with the Pittsburgh Pirates and, later, the Cincinnati Reds. But late in his career he spent a year with the Milwaukee Brewers, where he had a bit of a renaissance season and made his final All-Star team when he was 39 years old.

Parker’s career began in 1973 in Pittsburgh, and by the time he was 24 in 1975, he was one of the best players in baseball. From 1975 through 1979, Parker was a massive star. In those five years, he hit .321 and slugged .532 and thrilled audiences with a power and speed combination (he averaged 37 doubles, nine triples, 23 home runs, and 17 stolen bases per season in that stretch) that had an electrifying throwing arm in right field.

Parker won back-to-back batting titles in 1977 and 1978, and won the 1978 MVP award when he won two thirds of the slash-line triple crown (he hit .334 and slugged .585), and led the majors with a .979 OPS and 166 OPS+. The variety in his offensive game was on full display in 1978: he led the National League in total bases despite not leading the league in any of hits, doubles, triples, or homers (he had 32 doubles, 12 triples, and 30 homers).

While it was Willie Stargell who won the 1979 MVP as the spiritual leader of the “We Are Family” Pirates, it was Parker who was actually their best player—Parker hit 29 points higher, knocked in more runs, and had almost 100 more total bases than Stargell (who led the team in homers). In the 1979 postseason, Parker hit .341 and knocked in six runs across 10 games in two series victories, as he and Stargell cemented the legacy of one of the more memorable teams in baseball history.

Parker made the All-Star Game again in 1980 and 1981 but cracks were beginning to show in his game, and he missed about a third of the strike-shortened 1981 season. After another unhealthy season in 1982 and his worst season as a pro in 1983, Parker left Pittsburgh and joined the Cincinnati Reds as a free agent. He wasn’t great in 1984, but at age 34, Parker had a big comeback season in 1985 when he led the NL in doubles (42), total bases (350), and RBI (125) to go along with 34 homers. He finished second in MVP voting, the first season in which he received MVP votes in five years.

But also in 1985, Parker and several of his former Pirates teammates were caught up in the Pittsburgh drug trials, a big scandal in which several prominent major leaguers testified against men accused of drug trafficking. Parker and others received suspensions that were ultimately commuted, though he had to pay a hefty fine and do community service.

Back on the field, Parker had another good offensive season in 1986, but after struggling in 1987 the Reds sent the soon-to-be-37-year-old to Oakland. Parker won two pennants in two years with the As, and hit three homers in the 1989 postseason, which culminated in a World Series sweep of the Giants in the “Earthquake Series.”

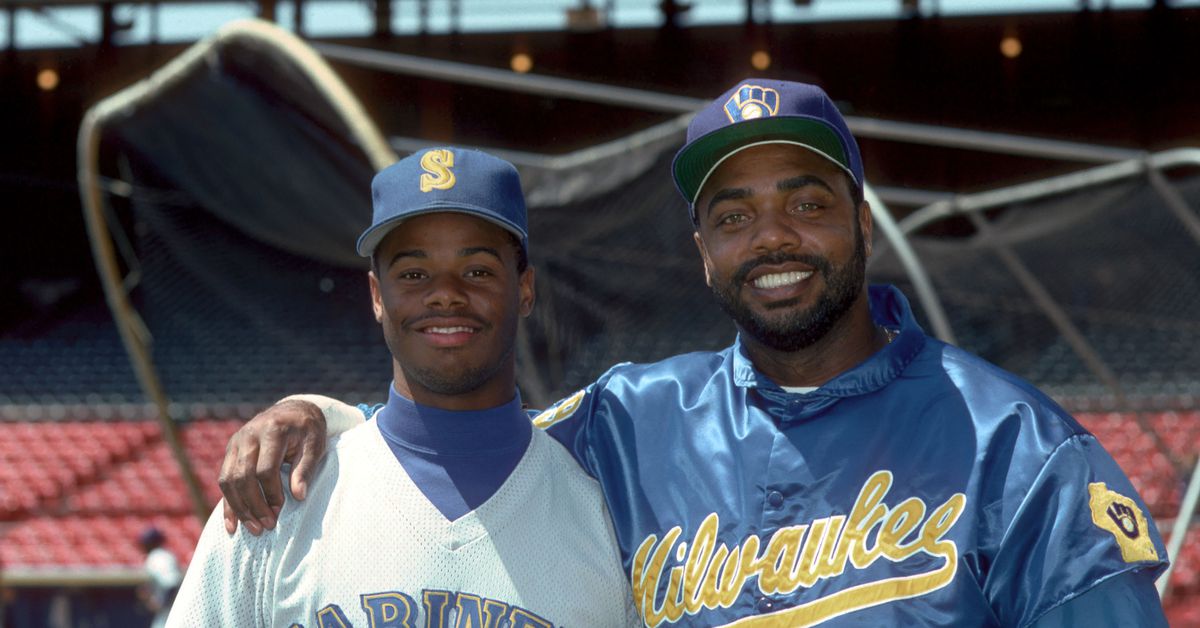

That December, Parker signed a two-year free agent deal with the Brewers, a move which reportedly convinced Robin Yount, also a free agent that winter, to re-sign in Milwaukee for what would be the last three years of his career. Serving as the team’s DH and also as a mentor to the mercurial youngster Gary Sheffield, the 39-year-old Parker had his best offensive season in years when he hit .289 with 30 doubles, 21 home runs, and 92 runs batted in. He was selected as a reserve in the All-Star Game, won a Silver Slugger, and got a few down-ballot MVP votes. He was revered as a veteran presence and was voted as the team’s MVP.

After the season, though, Milwaukee traded Parker to the California Angels for the young Dante Bichette. The move did not go over well, especially with Sheffield. In a 1992 LA Times article after Sheffield had been traded from Milwaukee to San Diego, he described his hatred for the Milwaukee front office, and Parker later wrote that the trade that sent him to the Angels was a last straw of sorts for Sheffield. Sheffield’s relationship with Brewer management deteriorated, culminating in the trade to the Padres before the 1992 season.

Parker, meanwhile, played one more season split between the Angels and the Toronto Blue Jays. He was 40 when he played the last game of his career. He finished with 2,712 hits, 526 doubles, 75 triples, 339 home runs, 1,493 RBI, 154 stolen bases and a career batting average of .290. He got MVP votes in nine different seasons, including the 1978 award and top-three finishes in three other seasons (1975, 1977, and 1985).

When it came time to vote for Parker for the Hall of Fame, he found support difficult to come by. While he got double digit vote percentage totals in all fifteen years that he spent on the BBWAA ballot, Parker never topped the 20.8 percent he received in 2000 and ultimately fell off the ballot. His lack of support was possibly due to a variety of factors; the drug trials, the feeling that he’d underachieved in the early 1980s and the accompanying feeling that it was partially his fault (due to drug use and bad conditioning), relatively poor defense. More analytic analyses of Parker’s career determined that his lack of defensive prowess and impatient hitting approach (he walked just 683 times in over 10,000 career plate appearances) harmed his overall value.

But Parker’s case was complicated, because of the intense peak that he’d achieved in the second half of the 1970s. For several years, the Cobra was a megastar who was in the conversation for “best player in the league,” and he was the best player on a team that won the World Series, even if his teammate won the MVP. Parker was included on Veterans Committe ballots three times after falling off the BBWAA ballot in 2011 before finally being elected on the most recent Veterans Committee ballot in December of 2024.

It is sad that Parker’s passing comes before he is officially inducted into the Hall of Fame, but it is comforting to know that he lived long enough to at least know that he made it. Parker’s legacy as a Brewer is small—he played one season for a below-.500 team—but he made an impact in the city, had a really strong season, and will be remembered by fans here in Wisconsin for a long time.