Decades of precedent began to crumble with an Instagram post.

The post, which caught the eye of Athletics scouts, included video of a nimble teenager vacuuming up ground balls on a dirt field in Japan. The kid pitched from the stretch and fired a fastball 92 mph. He planted his feet in the left-handed batter’s box and unleashed a smooth but violent swing.

His name was Shotaro Morii. The post advertised his aspirations of playing college baseball in the United States. The A’s, hopeful Morii would consider the nearly unprecedented jump to an MLB organization instead, sent Japanese area scout Toshiyuki Tomizuka to see Morii in person.

“This guy is bona fide,” Tomizuka reported back. “He’s a lot like the guys in the past that wanted to get out (of Japan) but couldn’t get out.”

Morii got out on Wednesday, signing a minor-league deal worth $1.5 million with the A’s that defies 30 years of cultural norms that held Japanese players should first compete in the renowned Nippon Professional Baseball league before coming to MLB.

The 18-year-old is the most significant Japanese prospect ever to dive into MLB-affiliated play without first playing in NPB. One agent with experience in Japan, who was granted anonymity due to the sensitivity of the issue, called it a “big deal” because Morii is breaking longstanding precedent and clearing the path for other elite Japanese amateurs to follow.

“The pressure from a cultural and league standpoint is so great that most of the time the country’s top amateurs don’t bypass the NPB draft to remain in Japan,” the agent said. “It will be interesting to see what happens with future high-level prospects.”

Twenty years ago, a teenaged Yu Darvish had the raw talent to sign directly with an MLB team but ultimately spent seven seasons in NPB before signing with the Texas Rangers. In 2012, Shohei Ohtani considered a direct path to MLB, but he, too, entered the NPB draft and played five seasons before beginning his star-studded MLB career. But Morii expressed clear interest in signing with an MLB club and desired to enter the professional ranks as quickly as possible — even if it meant defying 30 years of cultural norms.

“I did not want to regret my decision when I think about my whole life and whole career,” Morii said through Tomizuka shortly after the signing was official.

Morii is a two-way player who attended a small school in Japan and played most of his teenage career away from the tutelage of NPB academies, emerging late in his high school career as a projected first-round pick had he entered the NPB draft. His bonus, which comes out of the A’s 2025 international pool, is believed to be the largest ever for a Japanese player who did not play in NPB.

“I’m sure we’ve seen 100, if not 1,000, of those kinds of leads with a video of a player,” said Adam Hislop, the Athletics’ Pacific Rim scouting coordinator. “But this one turned out to be really good.”

Athletics scouting director Steve Sharpe believes it’s becoming more common for amateur Japanese players to consider bypassing NPB, though few have, as of yet, taken that path.

“They just never had the opportunity,” Sharpe said. “So Shotaro could really be opening up a door here.”

Since Hideo Nomo in the 1990s, nearly all Japanese baseball stars became NPB greats before coming to MLB. There was never a written rule forcing Japanese standouts to play in NPB before coming to MLB, but there was a cultural expectation understood both domestically and abroad. A few Japanese players went straight to MLB organizations after high school, but they typically were lesser prospects who, for one reason or another, were passed over by Japan’s best teams.

“It was viewed almost as something you do when your options are exhausted in Japan,” Japanese baseball writer Yuri Karasawa said.

Hard-throwing 22-year-old Junichi Tazawa was one of the first to challenge the norm. Undrafted out of high school, Tazawa was playing in a second-tier Japanese league when his prospect status soared in 2008. He would have been eligible again for the NPB draft, but Tazawa made clear his preference to sign immediately with a Major League team. No Japanese team drafted him, but opinions varied — even among MLB officials — about whether it was culturally acceptable for an MLB team to sign him without that NPB rite of passage.

“There has been an understanding,” New York Yankees general manager Brian Cashman told the New York Times in 2008. “There’s been a reason that Japanese amateurs haven’t been signed in the past, so we consider him hands off.”

Tazawa ultimately signed with the Boston Red Sox and spent nine seasons in MLB. In the wake of his departure, an unwritten yet highly specific “Tazawa Rule” developed in NPB stipulating that any Japanese amateur who skipped the NPB draft to play overseas would be ineligible to play in NPB for at least two years upon returning home. Japanese players who left early would face scorn and be blackballed if their MLB dreams fizzled.

That informal rule was scrapped under fair trade commission pressure in 2020, but the precedent remained.

“I think there’s still an immense amount of pressure from the high school baseball coaches to stay,” noted the agent. “That is still alive and well.”

The landscape, though, is changing.

Last February, Japanese standout Rintaro Sasaki skipped the NPB draft and signed a letter of intent to play college baseball at Stanford. Sasaki attended the same high school as Ohtani — Sasaki’s father is the school’s longtime coach — and hit a Japanese record 140 home runs as a prep superstar. He almost certainly would have been a top pick in the NPB draft, and if he’d signed, Sasaki would have been under NPB control for nine years.

Now on the Stanford roster, Sasaki will be MLB draft-eligible in 2026, having never played a professional game in his home country.

“Ohtani and (Yusei) Kikuchi are already overseas,” Sasaki told The Athletic this past spring. “I always thought one day, hopefully I can get there. They were big influences for me. Ohtani said, ‘Follow your instinct. That is what you decided. That is a path you need to keep walking.’”

According to Baseball-Reference, there were only 12 Japan-born players in MLB last season, but most had an impact. Kikuchi and Shota Imanaga received down-ballot Cy Young Award votes, Seiya Suzuki finished eighth in the NL in OPS, Darvish and Yoshinobu Yamamoto made key starts in the postseason, and Ohtani was the National League MVP.

Ohtani’s image is everywhere in Japan. His star status has eclipsed even Ichiro Suzuki’s. Ohtani is baseball’s greatest global icon, and there is not a close second.

“I think there’s a domino effect from Ohtani, really,” Karasawa said. “It’s Ohtani being on everyone’s television screens, being all over the place, proving that he can have that success and become the best player in the world.”

While the old guard speaks of tradition, Ohtani has let a younger generation dream of an uncharted future.

For a player drafted and signed into NPB to leave before playing nine years in the league, he must first be posted — with his team’s consent — and even then, the player signs with a Major League organization only if his Japanese team is paid a fee.

In the past year, the Japanese Professional Baseball Players Association has prepared a legal fight to push for a quicker route to unrestricted free agency. Roki Sasaki, the biggest NPB star coming to MLB this offseason, was posted after only five seasons, a shorter Japanese tenure than usual. NPB veterans have groused that, at only 23, Sasaki has not yet earned the right to leave. But he is leaving, and MLB teams spent the winter begging for his services.

It was yet another sign that the norms are changing. Asked whether he encountered pushback for his decision, Morii said simply: “No, there was not.”

“With young (Japanese) fans, they’re very open to decisions like this,” Karasawa said. “In fact, I think they’re very supportive. You see a lot of young people saying on Twitter, ‘This is the kid’s dream, so we should all support him.’ (The frustration) is more from the NPB teams’ perspective and the older generation thinking, ‘You’re supposed to start your career here in NPB and take this path that everyone else has done.’”

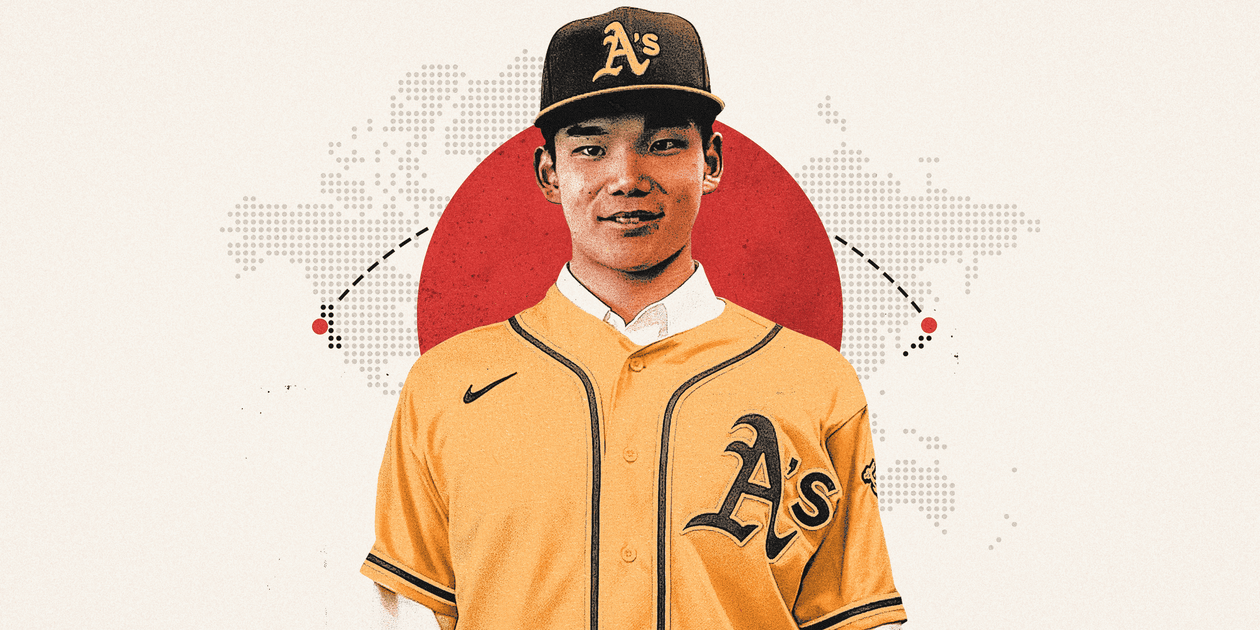

Morii signs his contract with A’s assistant GM Dan Feinstein looking on. (Courtesy of the Athletics)

MLB teams have noticed the shift. Their scouts in Japan still focus on the professional ranks, but they now scout Japanese amateurs as well.

“All teams do,” said one MLB scout with experience in Japan. “It’s just harder (to sign the high school players). There’s much more pressure on those players to (play) for the NPB.”

In Latin America, MLB scouts largely are given free reign. They can set up simulated games. They can watch showcases. They can visit local leagues. In Japan, Sharpe said, “It’s tough to see a practice.”

Even the Athletics’ pursuit of Morii began as a shot in the dark. Because of rules from the Japanese Amateur Baseball Association, the team could not have direct contact with Morii until after his high school season ended.

But despite obstacles when recruiting Japanese players — Sharpe compared the process to “playing Frogger” — the Athletics fell in love with Morii and found somebody willing to defy convention.

“I think he shocked me the most with his confidence,” Sharpe said. “He was so comfortable with the thought of leaving his native land, skipping the draft and actually signing. He would say it with such calm conviction. I hadn’t seen that yet with any of the other kids before that.”

Baseball America wrote that Morii has, “good hand-eye coordination and a knack for making contact,” along with the bat speed necessary to hit velocity and drive the ball to the pull side. On the mound, he has reached 94 mph with his fastball. “He will need to tighten his control,” Baseball America wrote, “but he has the stuff to be a legitimate pitching prospect if that was his only position.”

The A’s indeed intend to develop Morii as a two-way player, one of the reasons Morii chose to sign with the club. A’s officials struggled to contain their optimism about Morii’s potential.

“At one point I was excited to try to get a really good player,” Sharpe said. “That’s what we do. We want to compete. But then I was like, ‘Man, I want a backstage pass to this guy’s career. This guy could be outrageous.’”

Regardless of his development, eyes will be all over Morii both in Japan and overseas. If he makes it, he could be the first in a new wave of Japanese amateurs redefining the international pipeline.

“He’s carved his own way thus far,” Sharpe said, “and I’m not gonna be shocked if he has success carving his own way again.”

(Photo illustration by Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Photo of Morii courtesy of the Athletics / Graphic images from iStock)